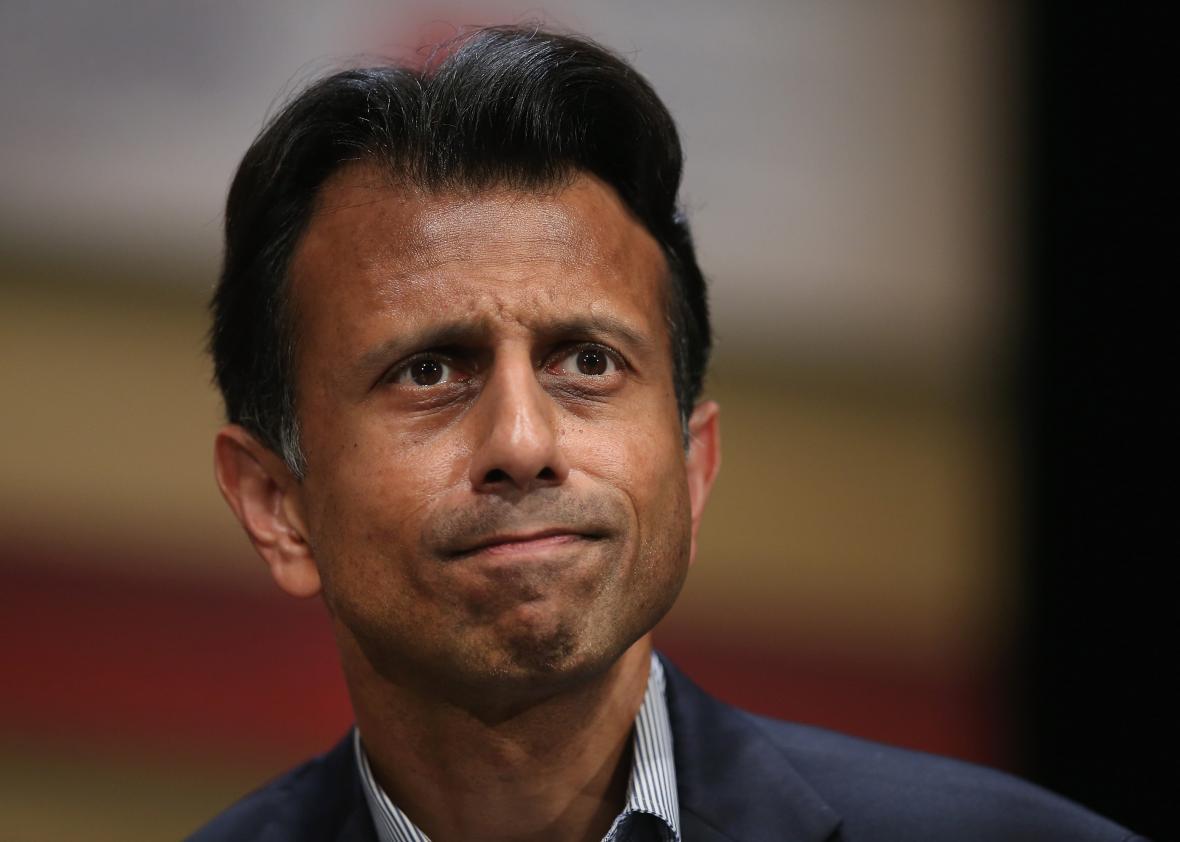

The term “anchor babies” has once again reared its ugly head this election season, spouting from the mouths of not just say-whatever Donald Trump but also I’m-my-own-man Jeb Bush and son-of-immigrants Bobby Jindal.

It’s shorthand for the idea that immigrant women purposefully and illegally come to the United States to give birth to their children, thus securing citizenship for their kids and perhaps also a chance to stay in the country themselves (even though in reality they can easily be deported). It gets thrown around whenever conservatives want to question the 14th Amendment guaranteeing citizenship to babies born on American soil.

The phrase, which turns a newborn into dead weight dropped like mooring, implies that these mothers are simply using their pregnancies as vehicles for their own desires. It dehumanizes them. They are transformed from mothers who want to bring life into the world to cherish and nurture it into creatures that use their own offspring to get what they want.

This dehumanization isn’t terribly uncommon, unfortunately. In fact it’s the way we often discuss the actions and choices that poor women and women of color make as mothers. We can’t pretend that using the term anchor babies is a one-off; it’s part of the fundamental way we both talk about and legislate the lives of poor women.

It’s particularly true when these actions are mere hypotheses with no data or evidence to show that women are actually making these choices. Anchor babies fall into this category. While some immigrants do come to the United States to give birth, they tend to be more affluent, arriving here as tourists with proper legal documents. Children born to undocumented parents make up a tiny slice of all American children. And if a mother comes to the U.S. to give birth in hopes of getting citizenship for herself, she’ll have to wait until her child is 21 and can petition for it.

Another dreamed-up bugaboo has recently popped up: poor mothers who deliberately poison their children to get housing. Maryland’s housing secretary warned a convention audience last week about a mother putting lead fishing weights in her child’s mouth, taking the child in for lead testing, and getting a free place to live at her landlord’s expense until the kid turns 18. When pressed, he said that he had no evidence of this ever taking place, but that “This is an anecdotal story that was described to me as something that could possibly happen.”

The poisonous mother is even more depraved than the mother trying to drop her anchor baby. This mother’s lead anchor roots her in a house, but her actions could kill her child or leave him physically or mentally impaired. Most people would barely recognize someone like that as human. But a poor woman’s poverty is assumed to make her act in barbaric, unthinkable ways to get what she needs. She doesn’t view her own children with the devotion and delight that we expect from any other parents. She is something other.

It’s a trope that’s been with us for some time. It dates at least as far back as the welfare queen, the mythical poor woman who defrauds the government out of anti-poverty funding rather than put in a hard day’s work. She started out as a real woman who stood trial for fraud in the 1970s. But she’s come to mean far more than that, standing in for a poor, usually black woman who has lots of children out of wedlock in order to get more government money.

This image took hold so strongly that it worked its way into legislation. After welfare reform passed in the 1990s and states were given wide authority to change their programs, many instituted welfare caps that cut poor mothers off of additional benefits after they have more than a certain number of children while enrolled. The caps have their origin in the House Republicans’ 1994 Contract With America, which called for “denying increased [benefits] for additional children while on welfare … to promote individual personal responsibility.” Others at the time more explicitly tied the caps to the idea that poor mothers were having extra babies just so they could get extra cash. The welfare queen, then, decided to add more people to her family not out of love and joy, but to cash them in like poker chips.

The legacy of this view remains with us today. Sixteen states give a family no extra money to care for additional children after a certain number. Yet welfare queens look nothing like reality for the people who receive public assistance. They have the same average family size as families who don’t need public benefits to get by. And there’s no evidence the caps work as intended.

These fantasies about poor mothers and women of color that treat them as some other species of human work their way into legislation in other ways. The Maryland housing official who warned against mothers poisoning children told the story to promote limits he wants to place on the liability landlords can face in lead paint cases. And of course anchor babies are doing important work for conservatives trying to make a case to end birthright citizenship, enshrined in the Constitution.

Once these policies get legislated, these mythical, monstrous mothers become canonized into our culture. And they shape the way we view poor mothers, to the point where it’s assumed that they are willfully neglecting and abusing their children when they leave them within sight to take a job interview or in a nearby park while they work. After all, if we believe poor women will poison their children or bring them into the world solely for financial gain, why would we believe that they try to do right by them at any other time?