Chris Suellentrop at Kotaku has posted an in-depth analysis of one of the more interesting findings from a recent Pew Research Center report on teens and technology: Despite sexist stereotypes that cast video games as a male hobby, teen girls love to play them. Sure, more boys ages 13 to 17 play than girls—84 percent and 59 percent, respectively—but both genders play a lot of games and a lot of different kinds of games. “More than 35 percent of the girls in the Wiseman and Burch study said they play role-playing games,” Suellentrop writes, adding that this is “a larger number than the 32 percent who said they played mobile games.”

But while games are popular with both boys and girls, there is a striking difference in how they play. Video games, for boys, are a social activity, but for most girls, gaming is a solitary pursuit. Even though the stereotype is that it’s girls who are always chattering with friends on digital devices, researchers found that boys were far more likely than girls to put gaming at the center of their social lives. Thirty-eight percent “of all teen boys share their gaming handle as one of the first three pieces of information exchanged when they meet someone they would like to be friends with,” Amanda Lenhart, one of the authors of the study writes, while “just 7% of girls share a gaming handle when meeting new friends.”

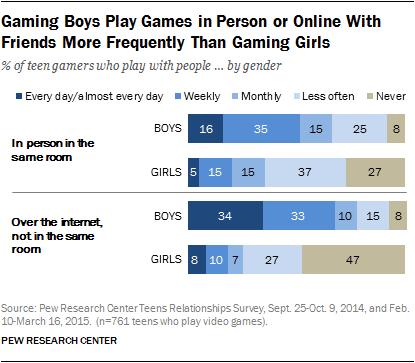

Boys were far more likely to play with other people both online and in person, as this chart shows:

Pew Research Center

What particularly interested Suellentrop was the revelation that even when girls play games online, they are far less likely than boys to turn on their mics to talk to other players. “Only 28 percent of the girls who play video games online use voice chat to talk to other players,” he writes, in contrast to the 71 percent of boys who play online do. Taken together, that means that talking with people during online games is part of life for the majority of teen boys, but, according to Lenhart’s estimate, only about 9 percent of teen girls.

Why do girls shun being seen playing video games, particularly to strangers, while boys embrace it? Suellentrop shies away from speculating, but the answer seems obvious to me, a woman who has played video games in some form or another since junior high school. There is just a huge gulf in the hassle factor. For women and girls, playing with friends, at least if you’re in a mixed-gender group, means that your performance is under a lot more scrutiny and that any failures are more likely to be blamed on your gender than if you were a guy. (For an illustration of this phenomenon, I recommend this famous XKCD cartoon.) If you’re online and other players realize you’re female, it can be even worse, with men saying abusive things to you just because of your gender. Games are supposed to be fun, so it’s not surprising that girls will gravitate toward modes of play that avoid all this stress.

No one should blame women and girls for choosing to play games in a way that renders them invisible to the larger gaming community, but an unfortunate side effect of this is that many guys who play are under the impression that it’s therefore a male hobby. The result is that women who do turn on their mics are often accused of being “fake geek girls” who are only doing it for male attention. Worse, the entire Gamergate controversy that exploded last summer was a direct result of too many male gamers seeing gaming as “their” hobby and women, particularly those who want to participate as equals, as interlopers who need to be run out. But by garnering so much attention, Gamergate inadvertently revealed that women are, in fact, a large part of the gaming world. Perhaps that is the nudge that was necessary to break the cycle of invisibility and silencing in the world of video game playing.