Andrew Jackson must have some really good dirt on Jack Lew. On Wednesday, U.S. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew announced that a woman will join Alexander Hamilton on the $10 bill in 2020. Whoever she is—and public input will help decide—she’ll be the first woman to appear on paper currency since Martha Washington graced the $1 silver certificate from 1891 to 1896. (Women’s-suffrage activist Susan B. Anthony graced a poorly received dollar coin at the turn of the 1980s.)

It’s about time. Last year, I wrote a Slate article calling for Andrew Jackson, who engineered a genocide of Native Americans, to be replaced on the $20 bill with someone less horrible. The idea quickly gained traction; soon, publications such as the Washington Post and Vox were talking about who might be a good addition to our currency. Even President Obama said that the possibility of putting a woman on the $20 bill was “a pretty good idea.” (Fun fact: I write about controversial topics, such as sadomasochism, polygamy, and rape porn, and I get a lot of hate mail. But I’ve never received more death threats than I did for the article about booting Andrew Jackson off the $20 bill. Dead white guys have vocal armies.)

If someone has to make room for a single representative of the other 50 percent of Americans, I would rather it be Andrew Jackson, but let’s be grateful for small victories. So who should join Hamilton on the $10? To start, she must be dead: Federal law states that no living person can appear on U.S. currency. Many prominent candidates, such as Harriet Tubman and Helen Keller, have been well-established. But here are some of the amazing women who deserve to be on the face of our currency, even if they’re not on the tips of our tongues.

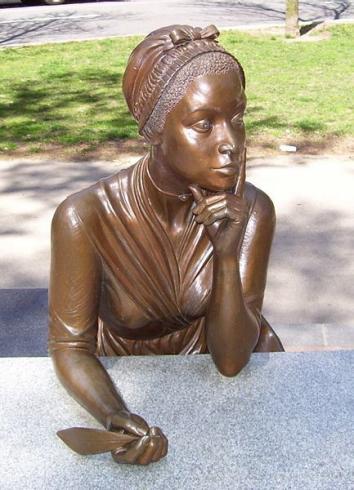

Phillis Wheatley

Americans love to celebrate hard work and self-made success, and few heroines have worked their way up from nothing quite like Phillis Wheatley. Originally from what is now Senegal, Wheatley was kidnapped into slavery in 1761 (her name, Phillis, was taken from the slave ship that transported her). Nevertheless, she learned English, Latin, and theology, and published her first poem in 1767. Six years later, in 1773, she became the first black American, first slave, and third American woman to publish a book of poetry, called Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. Her poetry was so remarkable that George Washington praised her talent and invited her to visit him in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Yet Wheatley’s road to success was rocky: After her poems had received international acclaim, doubts persisted about her authorship, and Wheatley had to (successfully) defend her work in court.

Deborah Sampson

Founding Fathers are a popular choice for U.S. currency, and Robert Shurtliff would be an ideal addition to that canon—not least because “he” was really Deborah Sampson, a woman who disguised herself as a man to enlist in the Continental army and fight for U.S. independence. Sampson wasn’t the only woman to fight in the Revolutionary War, but she was the most successful. She preserved her disguise for more than a year, even refusing professional medical care when she was shot twice in the leg to protect her secret. According to legend, Sampson removed the musket ball from her thigh herself with a knife and sewing needle, then returned to the battlefield and kept fighting.

Sylvia Rivera

Assigned male at birth, Rivera had a difficult path. Her father left shortly after her birth, and her mother committed suicide when Rivera was 3. Without family support, Rivera was homeless by age 11 and survived by working in the sex industry. Despite those challenges, Rivera rose to become one of the most influential figures in the anti-war, civil rights, and feminist movements, and was a central figure of the Stonewall Riots for LGBT rights. Throughout her life, Rivera aggressively campaigned for poor and homeless youth; one transgender activist described Rivera after her death as “the Rosa Parks of the modern transgender movement, a term that was not even coined until two decades after Stonewall.”

Lydia Maria Child

In a weird twist of history, Child is best known as the author of the poem that begins: “Over the river and through the wood, to Grandmother’s house we go.” But Child deserves to be known more for her activism than for her rhymes. As early as 1831, Child was a prominent advocate for the abolition of slavery. She published a book that called for slaves to be emancipated without compensation to slaveholders, which some historians have hailed as the first time a white person made that argument. But Child was way before her time in many respects—she campaigned for other important causes including Native American rights, interracial marriage rights, and women’s rights. On top of that, Child wrote some of the earliest American historical novels, edited the first children’s magazine, and published the first book specifically designed for the elderly.

Emmy Noether

Some might object to Noether’s face on the $10 bill, since the important mathematician spent much of her life in Germany, not the U.S. But it would be an honor to claim Noether, who immigrated to the U.S. in 1933 and is buried at the Bryn Mawr campus in Pennsylvania, among our national symbols. When Noether was a child, her mathematical education was delayed by German rules against women matriculating at universities. Nevertheless, Noether got her Ph.D. and spent the next seven years teaching mathematics at the University of Erlangen without pay. Her groundbreaking contributions to theoretical physics and abstract algebra finally earned Noether the title of “unofficial associate professor” at the University of Göttingen—but it was 1933 in Germany, and Noether was Jewish. After Hitler stripped Jews of German university positions, Noether found an official position—with a real paycheck!—at Bryn Mawr College. Upon her death, Albert Einstein called her “the most significant creative mathematical genius thus far produced since the higher education of women began.”

Honorable Mentions: Thankfully, I don’t get to include Grace Lee Boggs on this list, because although the American activist, feminist, and author deserves more recognition than she gets, Boggs, who is nearly 100 years old, is still alive. Other amazing women who deserve to be on our currency despite the one minor detail of still being alive include Sandra Day O’Connor, the first female Supreme Court justice; Aretha Franklin, the first woman to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; Nancy Dickey, the first female president of the American Medical Association; Ann Dunwoody, the first woman in the U.S. uniformed service to receive a four-star officer rank; and more—so many, many more.