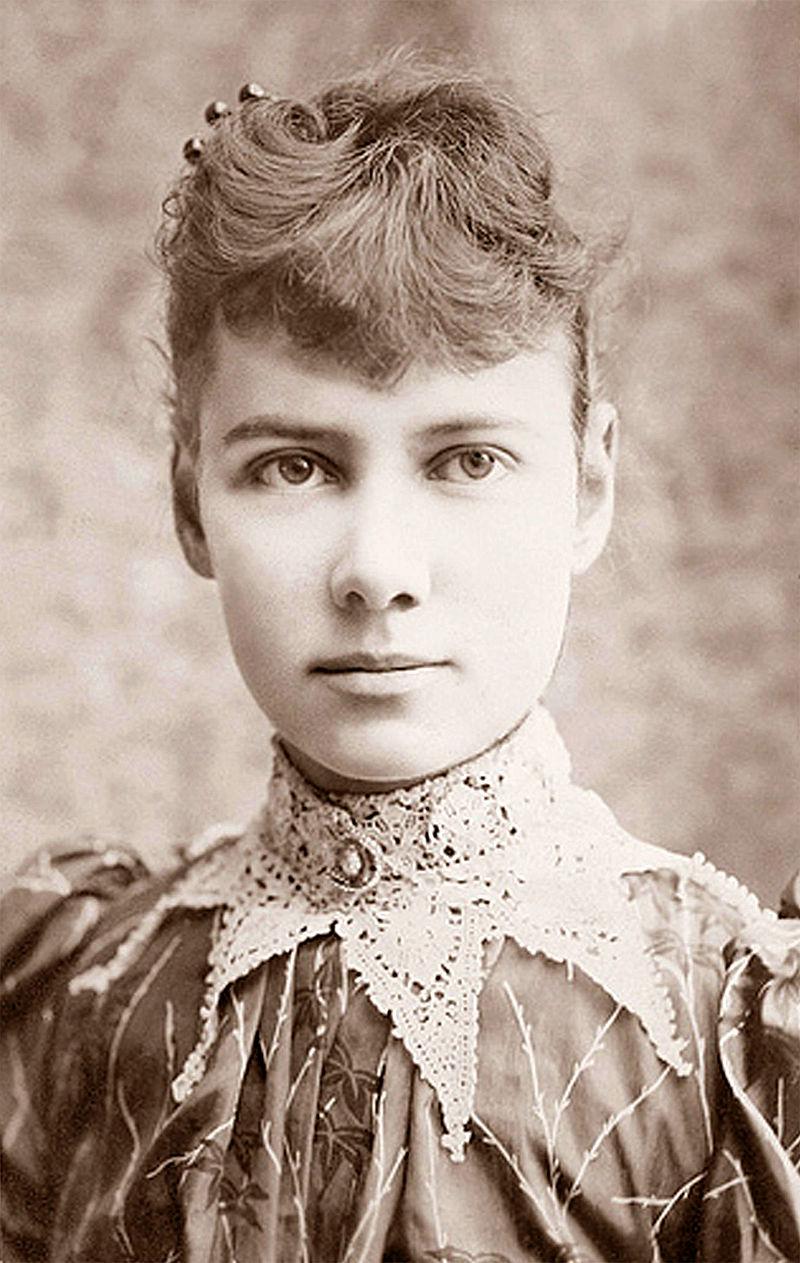

Today’s Google Doodle honors the 151st birthday of Nellie Bly, a woman who proved that stunt journalism isn’t always a bad thing. The remarkable Bly (whose real name was Elizabeth Jane Cochran) embodied gumption—she famously traveled the world in 72 days, for instance. But her most noteworthy work focused on the lives of the poor and disenfranchised in late 19th-century New York City.

The animated Google Doodle is accompanied by an original song from Karen O, titled “Oh Nellie.” Karen O sings, “We gotta speak up for the ones who been told to shut up/ Oh Nellie, take us all around the world and break those rules ’cause you’re our girl.”

The song’s first line—“Someone’s got to stand up and tell them what a girl is good for”—nods to the way Bly got her start. Her first writing gig, with the Pittsburgh Dispatch, came after she sent an angry response to a columnist who wrote a piece titled “What Girls Are Good For” about the need for women to stay at home.

And then she was off. Bly pretended to be a woman interested in buying an infant so that she could write an exposé on baby sellers. She spent hot summer nights in an infamous tenement building. One of her pieces carried the subtitle “Nellie Bly Tells How It Feels to Be a White Slave; She Tries Her Hand at Making Paper Boxes; Difficulty in Getting a Job; Most Work Two Weeks for Nothing; After One Learns the Trade It Is Hard to Earn a Living; A Fair Picture of the Work.”

Most importantly, on her very first assignment for the New York World, the 23-year-old Bly got herself placed in an insane asylum so she could report firsthand on the conditions. Talk about commitment. In the landmark piece “Ten Days in a Madhouse,” she wrote:

On the 22d of September I was asked by the World if I could have myself committed to one of the asylums for the insane in New York, with a view to writing a plain and unvarnished narrative of the treatment of the patients therein and the methods of management, etc. Did I think I had the courage to go through such an ordeal as the mission would demand? Could I assume the characteristics of insanity to such a degree that I could pass the doctors, live for a week among the insane without the authorities there finding out that I was only a “chiel amang ‘em takin’ notes?” I said I believed I could. I had some faith in my own ability as an actress and thought I could assume insanity long enough to accomplish any mission intrusted to me. Could I pass a week in the insane ward at Blackwell’s Island? I said I could and I would. And I did.

She did indeed. Bly’s 10 days in the asylum, where she witnessed mistreatment, neglect, and hopelessness, helped spur reform and made her a journalism star. Sadly, Bly died alone and poor in 1922 of pneumonia. But more than a century after her career began, her work remains relevant and affecting. She tried to make the powerful and well-off confront the fact that their decisions and buying habits affected real human beings, who were capable of real suffering.

NYU Libraries has collected her work here.