The day Apple joined Facebook in deciding to pay for its female employees to freeze their eggs, I joined a hundred or so fashionably dressed women—most in their 30s and 40s—at the Harvard Club in New York City to hear doctors discuss this game-changing technology over cocktails and hors d’oeuvres. This was the second egg-freezing party I had attended over the past two months. I wore my reading glasses so that I’d look older and not attract as many stares as I did at the last event, the ones that said, You and your young eggs don’t belong here. I am 25, a decade younger than most of the women seriously considering freezing their eggs. But they are not the ones for whom this technology was developed. I am.

In 2001, when I was 12, doctors removed my right ovary and fallopian tube in an emergency surgery. A benign cyst had caused a torsion that cut off blood supply—when I got to the emergency room, my ovary was dead on arrival. Eight years later, when I was 20, a cyst burst on my left ovary. This time, I was luckier: The doctors were able to save my remaining ovary in surgery. They said I could probably still have children later in life but recommended I consider freezing my eggs. “Who knows what your ovary will do next,” they said.

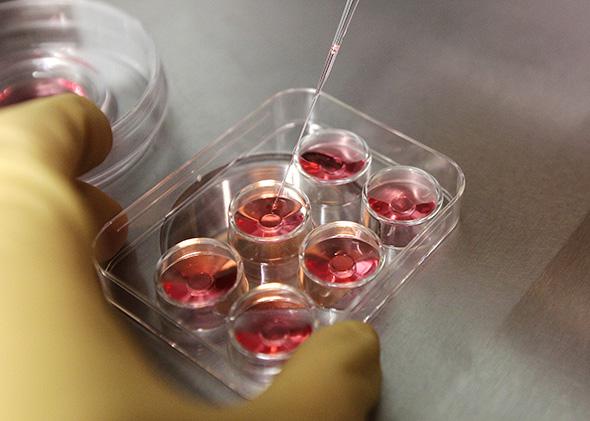

I was a junior in college at the time, much more concerned with not becoming pregnant than with not being able to become pregnant in the faraway future. I didn’t even know “egg freezing” was something women did. Was it safe? Was it legal? Did it involve a Petri dish?

Egg-freezing technology was developed in the 1980s for female cancer patients wanting to preserve their eggs before undergoing treatments that can cause sterility, such as chemotherapy. Young women with conditions such as endometriosis, lupus, or various forms of cancer are often encouraged to freeze their eggs. In addition to illnesses, certain drug therapies and surgeries that remove ovaries can also diminish fertility levels.

I vividly remember the night my left ovary was saved. After four ultrasounds, two ambulance rides, and multiple CT scans, my doctors in Germany still didn’t know what was wrong. The extreme pain in my side had me throwing up every 10 minutes—even when I was sprawled on a bed with my feet in stirrups, even when two doctors’ hands were alternating being inside of me. I remember staring up at the fluorescent lights before I was put under, wondering if this was going to become the night I lost my ability to have children.

When I woke up from surgery, my mother squeezed my hand and nodded her head: I still had my ovary. That is when we started talking about egg freezing over family dinners, not as a hypothetical political debate, but in the most personal terms.

Supporters of Facebook and Apple’s decision say the egg-freezing perk empowers women in the workplace. Critics argue it encourages women to put work ahead of motherhood. This is an important conversation, but it is not the entire conversation. Deciding to freeze eggs is a complicated and stressful decision—as opposed to an empowering one, or a work-life balance one—for many women who have medical reasons for considering it.

In 2012, when the American Society for Reproductive Medicine decided egg freezing should no longer be considered experimental, it stressed that though it is “a valid technique for young women for whom it is medically indicated … this technology may not be appropriate for the older woman who desires to postpone reproduction.” Both the ASRM and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists discourage egg freezing for elective, nonmedical reasons.

I have my own reasons for being reluctant to freeze. The high cost of freezing is a major issue for most women. But for us younger women still in school or with fledgling careers, it can make egg freezing impossible to even consider, despite what our doctors recommend. The numbers are overwhelming. On average: $10,000 per egg retrieval, $3,000 for the self-delivered hormone injections, $1,500 for the anesthesia, and around $500 per year for egg storage. At my initial appointment with my fertility doctor, I was informed that my insurance would not cover any of the costs associated with the procedure. “Not even because of my pre-existing medical reasons?” I asked. “Nope.” This isn’t just my plan: Most insurance companies will not pay for egg freezing. So, if I decide to freeze my eggs, I will pay anywhere between $15,000 and $25,000 out of pocket, depending on when I decide to have children. Important facts: I am a graduate student. I am unlikely to be hired by Apple or Facebook anytime soon. I have $250.03 in my savings account.

There are emotional and psychological aspects to consider, too. What if I have to undergo more than one cycle? How will the hormones affect my body during the process, not to mention long term? Since it will take my body a few weeks to fully recover from the surgery, will I have to take medical leave from school? What will frozen eggs mean to my potential future husband? How will freezing my eggs now affect how I go about living my life for the next five to 10 years?

And then there are the medical risks, which include blood clots and organ failure. The biggest risk with egg freezing is ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Because the hormones I’d be taking would enlarge my ovary, there is a chance it could swell to the point of rupturing. Ovarian torsion—which I unfortunately have a history of—can complicate OHSS, making this risk a more significant one for me. So, if I freeze my eggs, I risk losing my remaining ovary, killing all chances of becoming pregnant naturally later in life.

This is why I still haven’t frozen my eggs. I feel overwhelmed by the costs, risks, and potential emotional toll. I know that I want both a career and motherhood, but freezing my eggs does not mean I can rest easy, assured that I’ll be able to have both—there is simply not enough data yet to support promising success rates or offer anything close to a guarantee. I am less concerned with postponing child-bearing than I am with preserving what fertility I currently have.

Two weeks ago, during my first appointment with a revered fertility doctor in New York City, my feet were once again in stirrups. In the exam room, I stared up at the fluorescent lights. My doctor told me that my ovary looks “very active,” meaning I will probably only have to do one cycle of freezing, which makes the thought of paying for this the tiniest bit more fathomable. She says I’m an ideal egg-freezing candidate and that if I were her daughter she’d strongly encourage me to go through with this. Later, my parents not so subtly mention how excited they are to have grandchildren one day, and what a good mother I will be. As I leave my doctor’s office, she tells me that I should make a decision soon.