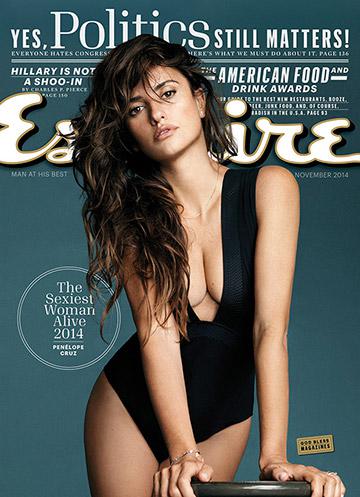

What would it take to write a Sexiest Woman Alive piece that isn’t horrible? Chris Jones’ icky profile of Penelope Cruz, Esquire’s Sexiest Woman Alive for 2014, is the latest icky entry in the icky genre. Jones uses rapt, creepy, overheated language to say practically nothing about his subject, except that she is “impossibly beautiful,” “has no physical flaws,” “looks like a thousand different women,” and “can be whatever we want her to be.” (So, nothing.)

Jones’ particular contribution to the grease canon elaborately compares a pure white bull being publicly, erotically, stabbed to death by matadors (“There was a growing intimacy between the matador and the bull in those moments. They had become familiars in each other’s heat”) to what the author/reader would like to do to Cruz, except that she does it to him first (“She picks her splattered white napkin off her lap and rises from the chair. All that remains on her plate is a bone and a puddle of blood”). The whole thing is pretentious, overwritten, and too satisfied with itself for landing its “feminist” reversal—that Cruz is the powerful swordsman, not the fetishized animal. Whatever, Esquire: What’s clear is that your writer had next to no time with the profile subject and is filling in the gaps with a labored allegory that yanks our voyeuristic levers while pulling Cruz closer to myth and far away from anything recognizably human.

But then, Esquire’s Sexiest Woman Alive profiles are generally terrible. I just read eight of them. Most presented the actresses and singers as irreducible mysteries, floating so high above the mortal (male) writers that they can only be described in terms of their effects. The voice of Scarlett Johansson, 2013’s Sexiest Woman, “is a raspy frequency in the air … the fact of it hangs in the air—always a little sandy, somehow broken down, as if she’d been singing all day.” (How does Johansson actually spend her day? When asked, “she holds her hands out, palms up, and smiles into a what-do-you-think shrug,” reveals Esquire helpfully.) They traffic in weirdo pious metaphors and exaggerations that aim to winkingly indicate how overcome a guy gets in the face of a gorgeous lady. But they just make men seem like drooling louts. (“Those liquid lips, those pearly ankles, those Boulder shoulders—Jessica Biel is a woman of many parts. … Now, at last, she is whole. Behold.”) The swampy atmosphere is compounded by such sins of expression as: “She [Rihanna, 2011’s Sexiest Woman] grabs her own radiant ass—she handles it, offers it—like it’s a rump roast.”

Is it even possible to write a Sexiest Woman Alive feature that doesn’t make you want to forswear words (and rump roasts) forever? The less objectionable instances—Ross McCammon’s 2012 piece on Mila Kunis stands out—read like straightforward profiles. Instead of fogging up the page with lurid masturbatory descriptions, they create space for the subject’s voice by asking questions and quoting answers. The editorial details that do make the cut help you imagine the woman’s personality, what it’s like to talk to her. “If she doesn’t understand what you’re getting at,” McCammon writes of Kunis, “she will give you the side-eye, but it comes off as genuine, not derisive.” Even that tidbit is a hell of a lot more interesting than the notion that Stephen Marche thinks Megan Fox resembles “a middle-aged lawyer’s shower fantasy.” (Unless, of course, these pieces are really less about the women than the male psyche—a viable possibility.)

But the McCammon solution—don’t talk about looks!—feels like a bit of a runaround. A Sexiest Woman Alive article is not a straightforward profile; it is text that accompanies the slideshow of the year’s Sexiest Woman Alive. Its theme is, straight up, the carnal allure of a female celebrity. Do we want to declare that theme unacceptable, at least in the hands of a male journalist? Or is there a way for men to write about ladies’ physical appeal without sounding like obnoxious creeps?

Perhaps, but it’s not easy, and I can’t point to anyone who is doing it well. (One reason might be because the male magazine definition of “sexy” is still incredibly limited—loosen that up and maybe detailed descriptions of body parts get interesting.) Why is it all so fraught? Because, as Amanda Hess pointed out in her assessment of World Cup thigh-light reels, commenting on women’s bodies has a long, painful history in a way that commenting on men’s bodies does not. For male stars, Hess writes, “sexual objectification is the icing, not the cake.” So when People trumpets its own Sexiest Man Alive, the results may be silly and frothy—“It’s a cold fall day in Montreal, but Channing Tatum is heating things up”—but not threatening. No one fears that Tatum will be reduced solely to his looks. (What? He’s a good dancer!) Meanwhile, that diminishment is a constant reality for women, no matter who they are, and every magazine article that reinforces it needs to work extra hard for the right to exist. I am talking to you, Esquire. All the bloody steaks and Aztec sacrifices aren’t helping.