Last week, a 20-year-old Nova Scotia man pleaded guilty to one count of manufacturing child pornography. In an agreed statement of facts read in court, the man acknowledged that nearly three years ago, when he was 17, he threw a small, booze-fueled party at his house with three other teenage boys and a 15-year-old girl. That night, he took a photograph of one of those boys, then 16, penetrating the girl from behind. She was naked from the waist down and was leaning out of a window to vomit onto the ground. The 16-year-old boy was smiling into the camera, holding the girl’s hip with one hand, and giving a thumbs up with the other. The person who took the photo is awaiting sentencing. The boy in the photo is now 19 and is awaiting trial for distributing the image. The girl died last year.

In court last Monday, Nova Scotia’s Chronicle Herald reports, the “girl’s parents and their supporters” sat in the gallery wearing “T-shirts emblazoned with the girl’s name.” Across Canada, you’ll find her name printed on bumper stickers, etched into rubber bracelets, and painted on decorative rocks in memorial gardens. But you won’t find her name in the local newspaper. In the Herald, she is the “victim” in a “high-profile Nova Scotia child porn case,” the girl “who later died after attempting suicide.” On Canada.com, her name is hailed as “synonymous with a nation-wide push for better laws around bullying, revenge porn, consent and how police respond to allegations of sexual assault,” but her name itself does not appear.

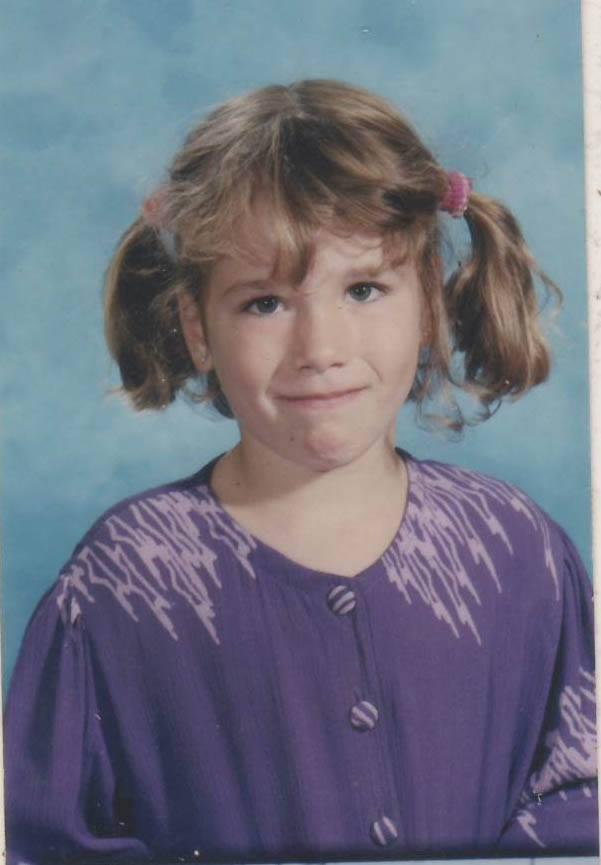

Photo courtesy Leah Parsons

That’s because the judge in the case has barred Canadian journalists and everyday citizens from repeating the girl’s name in newspapers, on television, over the radio, and on social media. He cited a portion of Canadian criminal code that bans the publication of a child pornography victim’s name in connection to any legal proceeding connected to that alleged crime. After several Canadian news organizations protested the ban last April, a second judge acknowledged that the victim “has achieved quasi-celebrity status where she is known by just her first name,” and that her own parents had “expressed their most vehement disagreement with the imposition of the publication ban.” But in a May 20 decision, he shrugged that the law is the law, and that Canadian judges are compelled to follow it. (Because the case is being tried in youth court, the names of the accused are banned from publication, too.)

In an age when it often feels impossible to keep information off the Internet, the publication ban has worked. In Canada and around the world, few realize that this ongoing child pornography trial is the culmination of a story that became internationally famous last year—a case that became synonymous with the miscarriage of justice in cases of sexual assault and harassment. The girl at the center of this trial is Rehtaeh Parsons. Remember her?

Within a few days of that November 2011 party, the vile photo had spread around Parsons’ school. Nine months after Parsons reported the incident to local cops, her family claims that the police ended their investigation into the incident, saying they didn’t have enough evidence to charge the boys with sexual assault, and brushing off the distribution of the photograph as a “community matter,” not a police one. In April 2013—after weathering years of bullying by her peers and the indifference of Canada’s justice system—Rehtaeh Parsons killed herself.

Almost overnight, her name transformed into an emblem of resistance against all who spread sexual photographs of young women without their consent. And her story—reported on CBC radio, CNN, and Dr. Phil—emerged as a parable for grappling with sexual exploitation in the digital age.

Courtesy Leah Parsons

The international attention compelled Canadian officials to sheepishly reopen Rehtaeh’s case after her death and finally bring charges in the incident that was previously dismissed as a “community matter.” It’s those charges—ones relating to child pornography, not sexual assault—that have finally led these horrific events to be aired in a courtroom. But for her supporters, there can’t possibly be justice for Rehtaeh when no one is even allowed to say her name and spread her story far and wide.

The media ban in child pornography cases is designed to protect victims from being exposed in the press. But at least in this case, some feel like the Canadian legal system is just protecting itself. “The agencies that weren’t there to protect her are the same agencies that are silencing her once again,” Rehtaeh’s mother, Leah Parsons, told me. “By taking the power of her name away, they’re stripping her of her voice a second time.”

It’s hard to overstate the impact of Rehtaeh Parsons’ name throughout Canada. “I think everybody who has heard this story, seen this story, were shocked, were saddened,” Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper said after her death. Rehtaeh’s story has since inspired a deluge of calls (and thousands in government funding) to a Halifax, Nova Scotia, rape crisis center; triggered national legislation to better address online exploitation; and sparked a six-month, $200,000 investigation of the police response in her case.

If you say the name “Rehtaeh” in Nova Scotia—it’s “Heather,” spelled backward—you’ll be met with “instant recognition” of the case and all of the issues it represents, Halifax freelance reporter Ryan Van Horne told me. But when Van Horne asks locals, “You know that victim in that high-profile child pornography case?” he draws blanks. The famous circumstances surrounding Rehtaeh Parsons’ bullying and death don’t fit the traditional conception of a child pornography case, which makes linking the two difficult if reporters aren’t allowed to use her name and photograph. And as with all crime stories, a human face inevitably increases readers’ interest and awareness. Taking Rehtaeh’s identity out of the discussion “diminishes the impact and the connection people have with the issue,” Leah Parsons told me. When people hear her name and see her face, “They realize it could be anybody’s daughter.”

Chronicle Herald reporter Selena Ross says that since the ban, the paper’s been forced to put her coverage “in coded language.” The paper’s report on last week’s trial includes details like, “Her parents … went public with their daughter’s story after her death.” Ross, who along with Frances Willick won the Canadian Association of Journalists’ annual award for outstanding investigative reporting for their coverage of Parsons, says this “is the only thing I’ve covered where readers are constantly asking for follow-up. Now, we’re not able to follow the story properly … A lot of people are unaware that there was a guilty plea and that things have turned out this way.”

Tying Rehtaeh Parsons’ full story to this new development is important, Ross says, because the initial police inaction toward Rehtaeh’s complaint raised important questions about whether the cops properly handled the sexual assault claim. Last week’s trial—which confirmed that a photo exists of Parsons vomiting during sex—should reaffirm public skepticism of how aggressively the police truly investigated the assault claim. But the public won’t have the opportunity to question those law enforcement actions if they’re not allowed to put two and two together.

Invested locals can piece together the advancements in Rehtaeh’s case by reading between the lines in the paper. But international supporters who don’t get the Chronicle Herald on their doorsteps aren’t hearing news of her case at all—and in a case where international pressure was central to reopening the investigation, some are worried the blackout will serve to protect officials who are still under fire over the incident. “In April of last year, the eyes of the world were upon us,” Van Horne told me. But “Nova Scotia is flying under the radar now,” he says. The publication ban effectively enables Canadian officials to “hide from the rest of the world … it’s all hush-hush. The message is, ‘We’re taking care of it, and we’re fixing it, but we don’t want anyone to know that we’re doing it.’ ”

Traditional media outlets in Canada have so far dutifully obeyed the ban. But the law will surely fail to keep Rehtaeh’s many online supporters from repeating her name—her name is popping up in the comments section of local news stories that won’t name her themselves. Rehtaeh’s father, Glen Canning, recently penned a piece for the Canadian online magazine Back of the Book that included his daughter’s name and photograph alongside his impressions of the trial. Van Horne, too, broke the ban on his personal website. The law “is unjust in this case and should be ignored,” he wrote. “Rehtaeh Parsons’ name brings power to any discussion about sexual consent, cyber-bullying, and suicide prevention.”

And on the Angel Rehtaeh memorial Facebook page, Leah Parsons posts daily Facebook updates urging her 48,000 followers to #RememberHerName. A few days ago, Parsons posted a note her daughter wrote at age 11, ruminating on her unique first name. “I wonder if my mom traveled to Africa in a canoe trying to find a great name for me. I wonder if she battled the lock ness monster. I wonder if she had fight Captain Jack Sparrow! I wonder when she got there what happened maybe she had to find a talking aceint tiger and he would tell her my name,” Rehtaeh wrote. Now, a year and a half after her death, the fight for Rehtaeh’s name continues.