In the space of the past month, 23 Columbia University students filed federal complaints claiming that the school had systematically mishandled their reports of sexual assault on campus. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand recruited two Columbia University students to stand by her side as she launched a campaign to secure more funding to better address the problem of college rape. Nearly 100 Columbia faculty members signed a letter urging the administration to improve its sexual assault policies. And the New York Times headed to Columbia’s campus to cover the rise of the student activists who are holding the administration to account. But before Columbia University became ground zero for the national political struggle over campus sexual assault, student journalist Anna Bahr spent six months quietly investigating the school’s rape epidemic, talking with victims and gaining access to secretly taped recordings of internal Columbia meetings on the issue.

In February, Bahr posted her findings to Bwog, an online offshoot of campus magazine the Blue and White. Her two-part series revealed an alleged serial sexual assailant who was allowed to continue operating on campus even after three separate victims lodged complaints, a male victim who slipped through the cracks of the university’s unresponsive rape crisis line, and a student who says she was raped shortly after attending a freshman orientation “Consent 101” workshop—by the workshop’s student leader. Bahr’s work sparked a response from students, administrators, national newspapers, and U.S. senators. It was the type of reporting coup that most student publications only dream of.

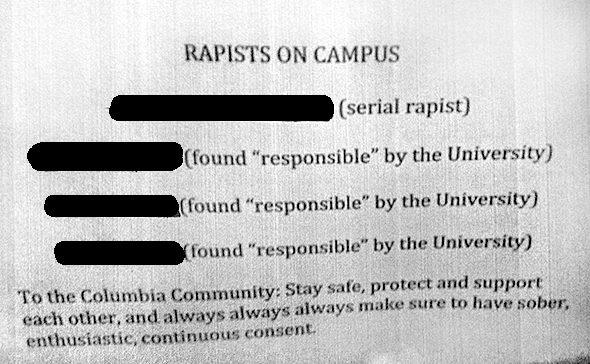

So it was strange when, last week, Bwog declined to report on the latest explosive development in Columbia’s high-profile sexual assault saga. Last Wednesday, anonymous notes began appearing on the walls of university buildings bearing the names of five students identified as “sexual assault violators on campus.” Student news and opinion blog the Lion covered the grassroots action as the list of alleged assailants—all of whom, the anonymous scribbler claimed, had already been found responsible for sexual misconduct through the university’s judicial process but were allowed to remain at school—spread from bathrooms to classrooms to printed fliers. Student newspaper the Columbia Spectator kept a running liveblog, tracking the campus reaction and hounding the university for a response. But Bwog remained silent on the list until this Tuesday morning, when it finally published an unbylined editorial, titled “List of Names of Alleged Rapists Written on Bathroom Walls,” that aired the details of the activist stunt—and swiftly condemned it. Bwog explained its tardiness: “On May 7, after receiving the first list, Bwog was in communication with senior administrators, who told us that publishing the list would violate Title IX as well as FERPA. That, and the desire to be responsible and not start a witch hunt, are the reasons that the uncensored list will never be published by the media. In addition, perhaps writing this list (and publishing the work of a campus ‘vigilante’) is not the best way to create a safer campus environment for victims.” It added: “We strongly encourage the prosecution through Columbia or the legal system of sexual assault perpetrators,” but “We are incredibly disturbed that people think this is a legitimate way to deal with the issue.”

There’s another explanation for the outlet’s delayed response, and perhaps for its editorializing, which it didn’t reveal: One of the names on the list was a Bwog staff writer.

In light of that detail—the staff writer’s name appears on a photograph of the flier obtained by Slate—Bwog’s five days of careful consideration look more like a stalling tactic. After all, other campus outlets posted photographs of the list of alleged rapists with the students’ names blacked out, an easy call that would both protect the publications against lawsuits by the named students and also allow them to avoid tacitly supporting the activists’ intended goal of publicizing the names of alleged offenders. (Bwog belatedly adopted the same strategy in its unbylined editorial.)

Ten hours after it condemned the “vigilante” actions of anonymous activists with no mention of the staff writer’s involvement, Bwog’s top editors and publisher posted a “Statement of Conflict of Interest” to its website, in which they admitted that “On May 7, allegations that a member of our staff had violated Columbia University’s Gender Based Misconduct policy were brought to our attention by an anonymous tip.” By that point, anyone who had seen the list on campus knew exactly what they were talking about. The statement continues: “Bwog does not condone rape culture. We are firmly committed to fostering a safe community. Over the last six months, we have made coverage of sexual assault on this campus a priority in our reporting. As a news publication, we consider it our responsibility to further transparency around this issue and have been dedicated to increasing its visibility and facilitating discussions on and offline.” The statement goes on to say that the writer in question has resigned at Bwog’s request in order to prevent a “conflict of interest” that would impede the blog’s “ability to accurately report on campus activism” and also effectively promote “a rape culture we so firmly stand against.” (The now-former staff writer did not return Slate’s emailed request for comment.) The statement added: “Our decision does not reflect a position on the innocence or guilt of this former staff member, nor does it comment on, take a position on, support, implicitly or explicitly, any allegations of fact or law made against such person. … We would like to reiterate once more that until proven true in a court of law, any and all allegations made are merely that, allegations.”

This statement—which trades anti-rape buzzwords with legalese in every other sentence—is actually a pretty impressive response to the legal, moral, and campus pressures that Bwog has suddenly been forced to confront. (The post was published with two tags: “clearly our lawyer looked over this” and “sexual assault.”) Language aside, Bwog’s decision to have the accused writer resign was a difficult and necessary choice to avoid an appearance of conflict, particularly as campus sexual assault has become one of Bwog’s marquee areas of coverage. (And as Bwog’s previous coverage of sexual assault at Columbia has demonstrated, the university itself is not always so committed to making these tough calls.) But while it’s understandable that the publication waited to report on its own writer until it assessed its legal responsibilities, it was wrong to, in the meantime, publish a blog post admonishing the activists who distributed the list, without mentioning that one of its own staffers appeared on it. Also, it’s a little depressing to watch a journalistic outlet claim that the only acceptable response to injustice is through educational and legal institutions, some of which have been previously revealed as incompetent by said journalistic outlet.

Bwog contributor Bahr agrees. When the unbylined editorial hit, Bahr emailed Bwog editors expressing disappointment that it had published anonymous commentary in the publication’s collective voice. “I am truly confused about why Bwog thinks it has the authority to gauge what constitutes a ‘legitimate’ means of responding to and addressing assault,” Bahr wrote in a letter obtained by Slate. “You as well as anyone know that ‘legitimacy’ does not and has not factored into the handling of countless assault cases on this campus.” (Through its publisher, Bwog declined to comment for this story.) Still, I’m not interested in unloading the blame for this situation on a student publication run by hardworking young volunteers. (“With this exception, Bwog has covered sexual assault very diligently,” Bahr told me. “If anything, I think this scrutiny will push them in a direction of paying even more attention to how they cover it.”) The subtext of this incident tells a more important story about how all institutions grapple with rape in America. A couple of months ago, Bwog was a central outlet for airing the allegations of campus sexual assault victims who said they weren’t being heard by their university. Now that it’s found a friend on the other side of the disciplinary hearing, its approach is a lot more complicated. It’s important for campus publications to tell the stories of both sexual assault victims and accused assailants (and Bahr contacted many accused students for her February piece, though none replied). But when the institution (the paper, the school) tasked with investigating the claims of complainant and respondent puts its own interests first, everyone suffers.

In Bahr’s investigation, she quoted Stanley Arkin, a lawyer for one sexual assault victim at Columbia, who said: “The University weighs discretion more than justice. It is trying so hard to keep these acts discreet that, to some extent, the process belies an effective justice.” That’s a lesson that both university administrators—and the campus journalists tasked with holding them to account—could benefit from. The difference is that Columbia is a powerful institution that has been legally required for decades to equitably deal with rape on its campus, while student journalists are all just learning as they go.