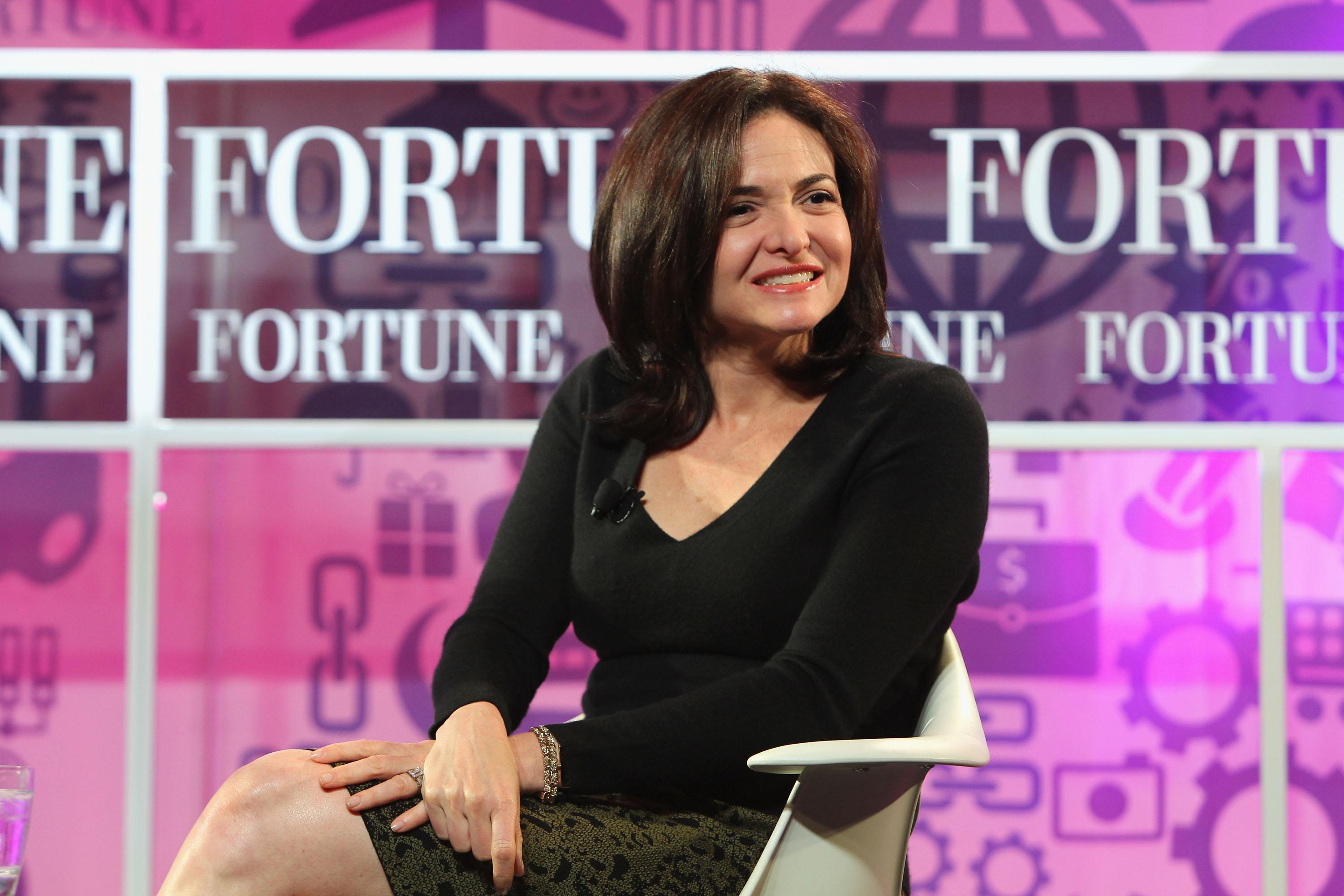

Job-searching women have long expected to make less money than their male counterparts (which firms know, so they offer us less). We also tend to flinch from haggling with our bosses once an offer hits the table. But Sheryl Sandberg and a new generation of working feminists have inflamed our timid souls: We understand now that negotiating for a higher salary can help shrink the gender pay gap and that when we value our time and expertise, so do our employers. Plus, what’s the downside to floating a better number to the higher-ups, like a plume of smoke from the burnt offering that is our endless drudgery?

The worst they can say is no.

But, in fact, bosses can do a lot worse than say no—they can assign us fewer projects because we lack team spirit. They can label us rude and uncooperative. They can even rescind our job offers.

The blog Philosophy Smoker hosts the tale of W, a woman who says she was offered a tenure-track philosophy position at Nazareth College, a liberal arts school in Rochester, N.Y. She replied, she says, by emailing the selection committee:

As you know, I am very enthusiastic about the possibility of coming to Nazareth. Granting some of the following provisions would make my decision easier[:]

1) An increase of my starting salary to $65,000, which is more in line with what assistant professors in philosophy have been getting in the last few years.

2) An official semester of maternity leave.

3) A pre-tenure sabbatical at some point during the bottom half of my tenure clock.

4) No more than three new class preps per year for the first three years.

5) A start date of academic year 2015 so I can complete my postdoc.

She ended the email by writing, “I know that some of these might be easier to grant than others. Let me know what you think.”

Their alleged response:

Thank you for your email. The search committee discussed your provisions. They were also reviewed by the Dean and the VPAA. It was determined that on the whole these provisions indicate an interest in teaching at a research university and not at a college, like ours, that is both teaching and student centered. Thus, the institution has decided to withdraw its offer of employment to you.

Thank you very much for your interest in Nazareth College. We wish you the best in finding a suitable position.

The abrupt turnaround from Nazareth shouldn’t necessarily surprise us. Although we can’t know the full circumstances surrounding this alleged exchange (in an email, the college declined to comment on personnel issues), research shows that initiating negotiations while female can be dangerous business. In a 2007 study, Linda Babcock and Hannah Riley Bowles found that men and women were less likely to want to both hire and work with women who asked for raises; the go-getting femmes were perceived as demanding and uncollegial. Raise-seeking men, on the other hand, faced no backlash at all: Not only did the study participants tend to grant them lots of (hypothetical) perks, but socially their images went untarnished. In a follow-up paper published in 2013, the same year that Lean In hit bookshelves, Bowles and Babcock isolated some strategies—blaming another supervisor for the ask, “expressing concern for social relationships”—that helped women navigate the raise minefield by making them appear more feminine. Yet the line between aggression and gently assertive charm is thin. “Even if a woman successfully negotiates a higher wage,” the researchers warn, “she could dampen her long-term earnings” by “[alienating] colleagues who might be important to her career advancement.” (For more on bargaining and gender stereotypes, check out this 2009 paper from the Negotiation Journal.)

Again, the W/Nazareth situation may be more complicated than what has surfaced in the blogosphere. Still, if the hiring committee was already wavering, there are not entirely kosher reasons that W’s request for “the usual deal-sweeteners” might have pushed them over the edge. “It’s not that women can’t negotiate, but they have to be much more careful about how,” Babcock told me on the phone. “Men can use a wide variety of negotiation approaches and still be effective. But women generally need to pull off a softer style.”

The reasons for this are complex, but they boil down to “what’s normal, what the norms are,” says Babcock. “We’re used to seeing women being less aggressive, more soft. And when people don’t behave the way we expect them to, there are often negative consequences: You’d see similar social penalties if a man in a business context broke down and cried.”

I asked her what W could have done differently in light of the negotiation double standard. “Email is hard,” she replied. “It feels very direct, cold, and assertive, and it’s easy to misinterpret.”

Still, based on what we know, Babcock thinks W did a lot of things right. She expressed enthusiasm and showed that she respected the hiring committee’s constraints. “If a man had sent that message,” Babcock says, “I suspect it might have been dismissed as a rookie mistake. Rescinding the offer rather than just refusing the requests is horrifying.”

Perhaps more horrifying are the tortured conditions of the academic job market, which make this kind of alleged bait-and-switch possible. Still, as Erin Gloria Ryan wrote on Jezebel, the story has impact beyond academia. Take me, for example. I once asked for a raise. But I would never have done so if 1) I had not been inundated in Lean In–themed cheerleading, 2) I were not writing an article about it for Slate, and 3) I had any inkling that tales like W’s were possible. As Babcock said on the phone, the Nazareth debacle “imposed so many costs on so many people.” The department (allegedly) didn’t get their candidate. W (allegedly) didn’t get the job. And women everywhere can now draw the conclusion that they are better off acquiescing to the wage gap than advocating for themselves and, perhaps, winding up with nothing at all.