Last week, Alex Trebek appeared on Fox News to talk about latest Jeopardy! mastermind Arthur Chu and to speculate as to why women are less likely to win at the game than men are. “Women contestants, when it comes to a Daily Double, seem to want to wager [less] because they figure, ‘Oh, this is the household money, this is the grocery money, the rent money,’” Trebek said. “Guys say, ‘Wait a minute, I’m playing with the house money. I’m not taking any money home unless I win the game, so I can go whole hog on this wager.’ Women are more cautious in that regard.” But “that’s changing,” Trebek added. “We’ve attracted more women to the show … and they’re getting a little more adventurous.”

Do women wager less in Jeopardy!? And is that a bad thing? We crunched the numbers of Daily Double bets dating back to 1984—the year that Trebek first took the podium to kick off the quiz show’s current iteration—and found that although there is no drastic gender difference in bet size, there is a consistent gap in male and female wagers that’s persisted across the show’s 30-year run.

A few caveats: We pulled data from J! Archive, a website that keeps a record of contestant names, questions, answers, wagers, and winnings stretching back to 1984. But the archive is not complete, particularly for games from older seasons. And since the archive doesn’t code contestants by gender, we assigned gender by identifying names that are more than 85 percent likely to be male or female. That means some names just can’t be given a gender—monikers like Renzo or J.D., though we have our hunches—and our system is susceptible to some errors. (Is every person named Chris male? No, but more than 85 percent of them are.)

So: We found 10,608 Daily Double bets made between 1984 and 2014 that could be identified as being from a man or woman. In that time period, the average male Daily Double bet was $1,963, and the average female Daily Double bet was $1,675. But men, on average, had accumulated more money before landing on the Daily Double than women had. If you look at Daily Double bets as a percentage of the player’s pot, the gap between male and female wagers is slim: Men bet an average of 42.97 percent of their current earnings on Daily Doubles, while women bet an average of 41.15 percent of their earnings.

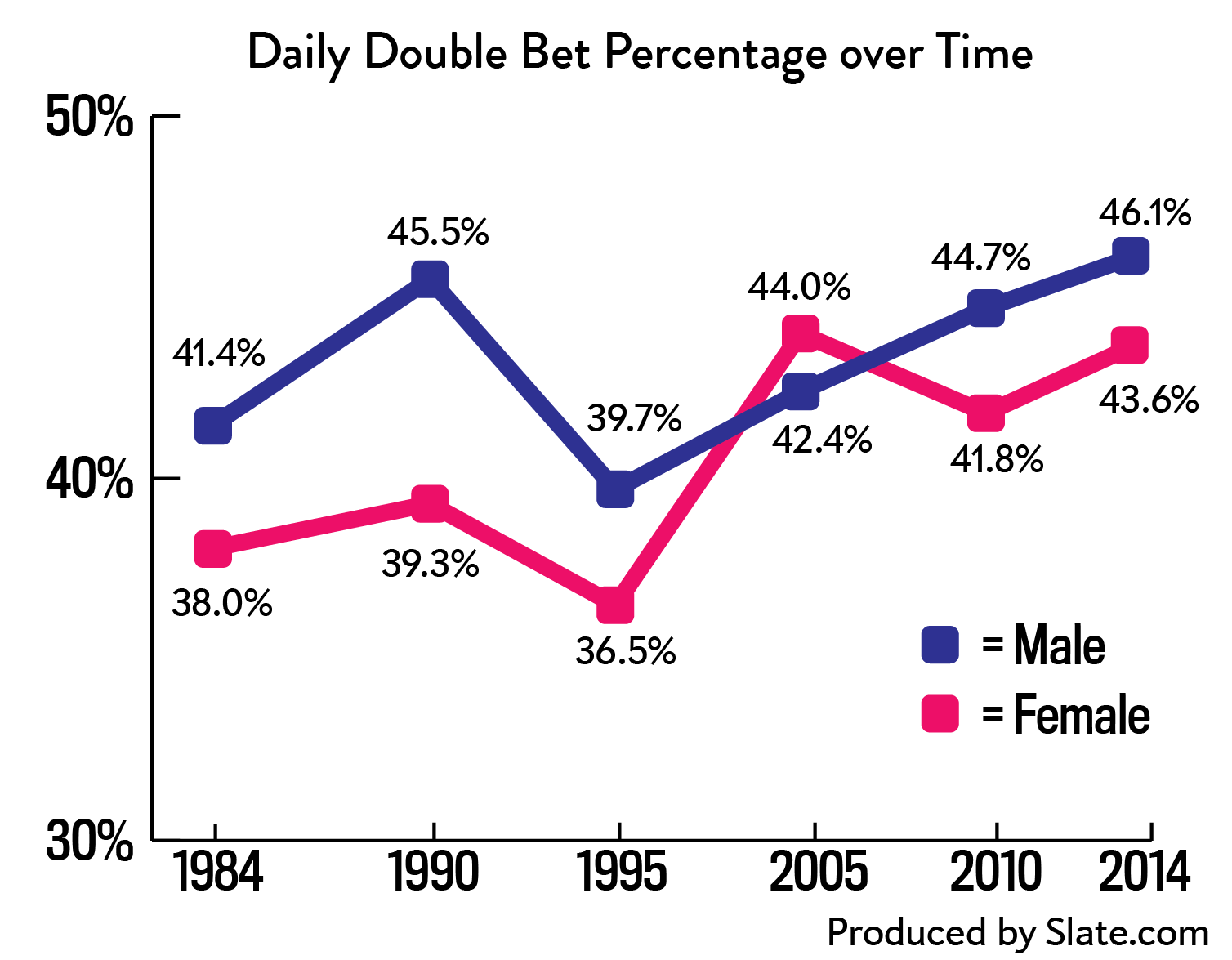

Women are, in fact, betting more than they did when the show kicked off. But so are men. And the uptick in player riskiness isn’t a clear trend; the numbers have fluctuated during the past three decades:

Trebek is correct that women tend to wager a bit less than men and that they’re wagering a little bit more than they used to. (Though for two years in our sample—2003 and 2004—women actually wagered more than men did.) What’s less clear is whether a more conservative bet actually constitutes a poor strategy for female players. According to our data, women win Jeopardy! less often than men do. During the past 30 years, 39.9 percent of Jeopardy! contestants have been women, and they’ve won 30.3 percent of games. But the gap can’t be explained by gendered betting strategies. Imagine an alternate form of Jeopardy! with no betting involved—no Daily Doubles or Final Jeopardy questions. If women were actually handicapped by their lower wagers, they would be more likely to win at this form of the game. But when we tallied Jeopardy! earnings without the Daily Doubles or Final Jeopardy questions included, we found that women would only win at this form of the game 29.5 percent of the time. They actually fare slightly better in the betting version. Of course, there could be other variables that would come up in this revamped game, but our findings do suggest bets alone can’t explain the discrepancy in male and female wins.

We’re not the first people to look at gender in Jeopardy!. A 2011 study conducted by the Swedish Institute for Social Research found that female contestants bet less when they were competing against men; when paired with two male opponents, women wagered 25 percent less of their accumulated score than they did when paired with two other women. But the researchers also found that women performed “significantly better” when competing against the men, despite their more conservative betting strategies.

So what accounts for the gender gap in Jeopardy! champions? It’s partly because there are fewer female contestants overall, but that doesn’t totally explain the difference. One possibility is that the questions themselves are gendered. (In our data set, women had a slightly lower rate of success than men on Daily Doubles, answering correctly 62.3 percent of the time compared to 67.8 percent for men.) The people who create Jeopardy! clues are overwhelmingly male: Male researchers on the show outnumber female ones 5 to 2, and male writers outnumber female ones 7 to 2. And there’s some indication that their clues have been historically tilted toward the male mind. One 1998 study published in Sex Roles found that “men selected and correctly answered a disproportional number of questions from masculine topic categories, which appeared more often during the first round of play. Women chose more feminine and neutral questions than did men, and correctly answered those questions at a proportional rate.” If it’s true that the first round of play is weighted toward men—and if some categories of human knowledge can really be masculine or feminine—then that could definitely tilt the game. Getting answers right from the get-go allows a player to control the board and, if he’s winning, have more to wager later.

So where does that leave us? It’s easy for Trebek to say that female contestants need to get “a little more adventurous” with their Daily Double bets. That’s the Lean In explanation for Jeopardy!’s gender gap. It’s more difficult to entertain the other possibilities: That 1) the game itself may be stacked against women, 2) women aren’t as good at Jeopardy! for reasons that elude us, or 3) women are too busy worrying about grocery money to study their potent potables.

Correction, March 5, 2014: This post originally misstated Arthur Chu’s last name.