“Skating, for Tonya, is her ticket out of the gutter.” That’s what figure skating coach Diane Rawlinson said of rising teen star Tonya Harding, who she had plucked from a broken Portland, Ore., home and shot onto the ice in the mid-1980s. “She lives in a terrible rental house. There’s no supervision at all. She has no direction. Tonya would have nothing in her life if it wasn’t for her skating.”

We all know what happened next. Harding’s husband, Jeff Gillooly, conspired to whack Nancy Kerrigan out of competition at a practice session before the 1994 U.S. Figure Skating Championships, the event that would determine the American delegates to that year’s Winter Olympics. Kerrigan recovered and won the silver medal, then reigned over Disney floats, game shows, TV specials, and charity spokeswoman gigs. Harding biffed her Olympic routine, pleaded guilty to conspiring to hinder the prosecution of the attack, and was barred from competition for life. She turned to exploitation films, celebrity boxing, and landscaping work. She never got her ticket out. Now, 20 years after the Kerrigan attack, ESPN’s new documentary The Price of Gold (which airs this Thursday) complicates the narrative of the American skater who triumphed against adversity to great fortune, and the one who sank to the bottom after a brazen attack on her biggest rival.

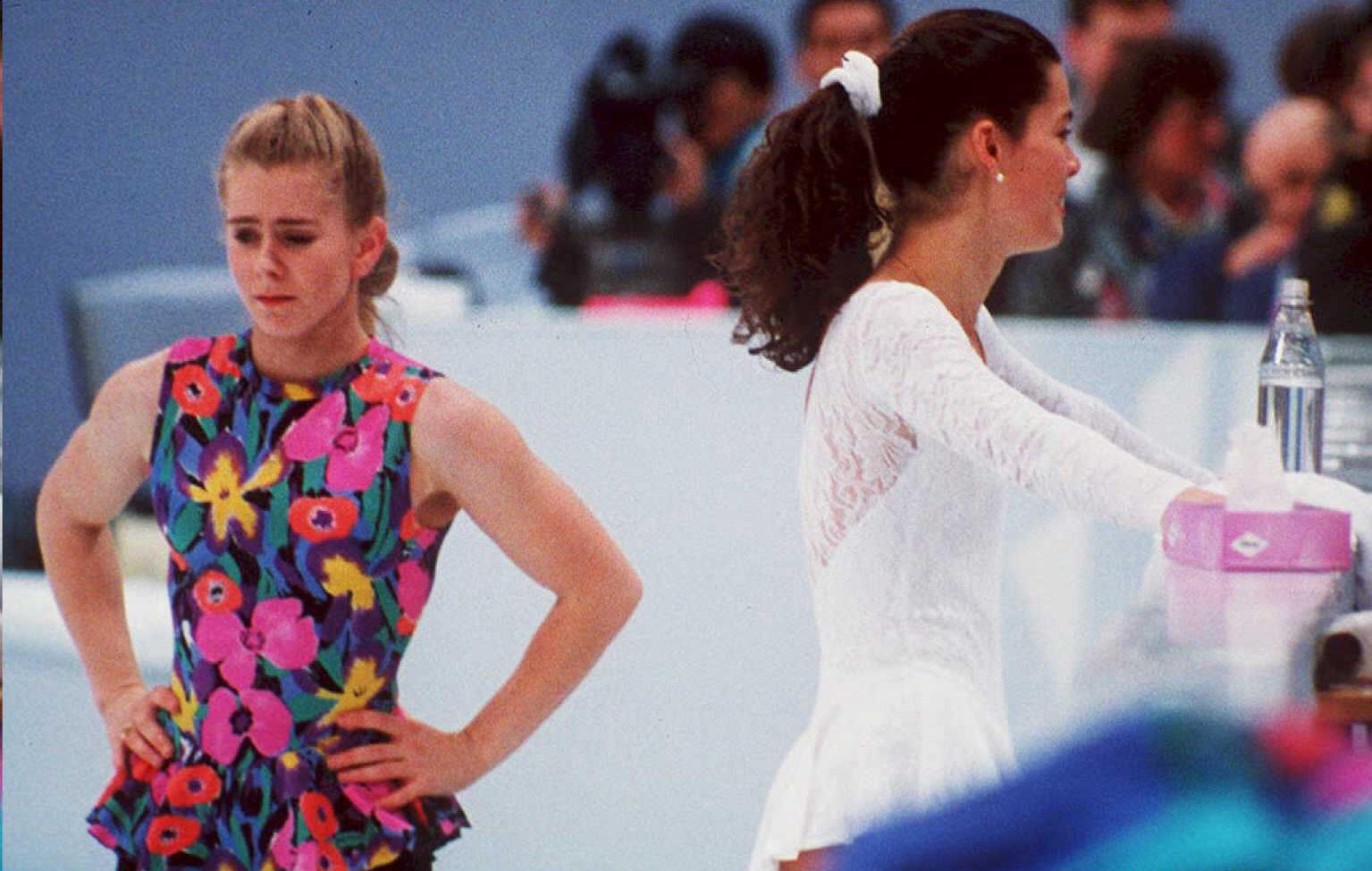

As Nanette Burstein’s documentary makes clear, the Kerrigan-Harding affair unfolded in a commercial landscape in which economic potential hinges on appearance as much as it does athleticism. By the early ‘90s, Kerrigan and Harding were toe-to-toe in American figure skating competition, but when it came to monetizing their skills, Kerrigan was skating on an elevated plane. Though both athletes emerged from working-class backgrounds, Kerrigan was blessed with patrician good looks and a sophisticated air that easily courted corporate sponsorships and Hollywood attention. “Nancy looked like she was wealthy,” is how Boston Globe reporter John Powers puts it in the documentary. Harding, counters Connie Chung, was the “girl with frizzy blond hair from the wrong side of the tracks.” And their performance styles reinforced the divide: While Harding powered through technical routines, Kerrigan danced.

And so Kerrigan’s face soon became as famous as her feats on the ice. She began raking in endorsements early in her career, filming spots for Campbell’s soup, L’Oreal, and Reebok; in 1992, she starred in a televised Christmas special. But even when Harding became the first American woman to land a triple axel in competition in 1991, no one wanted her to sell anything. “She was a great skater. I was a great skater. But she was treated like this big queen,” Harding says in the documentary. “She’s a princess, and I’m a pile of crap.” At one point in the film, Harding recalls wearing a bright-pink costume in competition that she had sewn herself. “It was really pretty!” she says. But “one of the judges came up to me afterwards and said … ‘If you ever wear anything like that again at a U.S. championship, you will never do another one.’” Harding shot back that until the judges gave her $5,000 to buy a designer piece, “You can get out of my face!” Meanwhile, as Sarah Marshall detailed in The Believer this month, Kerrigan had Vera Wang designing her costumes gratis.

As competition heated up before the 1994 Olympic Games, Harding pinned all of her athletic and economic hopes on the gold. If she cinched the medal, she believed that “someone would ask her to endorse something,” as Chung, who covered the scandal for CBS, says. While Kerrigan could profit off of personality and appearance without taking the gold (she won a bronze in 1992 and a silver in 1994), Harding needed to defeat everyone else, at any cost, to collect anything from her skating prowess. So even as federal investigators zeroed in on Harding in connection with the Kerrigan assault, she told reporters at a pre-Olympics presser that her mind was consumed with “these little dollar signs in my head.” When Harding turned in a dismal performance in Lillehammer, punctuated by a false start thanks to a broken lace, it marked the end of a career that had never brought Harding dividends. Meanwhile, the scandal that loomed over the games attracted Super Bowl–level viewing numbers and vaulted ice skating to an unprecedented level of popular interest. Everybody made money except for Harding.

But what would have happened had Harding won? Perhaps she had miscalculated. Even if she had managed to neutralize Kerrigan at the Olympics and take home the gold, it’s unlikely that Harding would have inherited all of Kerrigan’s endorsements, too. She might no longer have been dismissed as “crap,” but she’d never be the queen. And the numbers suggest that, for female athletes, winning still isn’t everything. Last year, Maria Sharapova earned almost twice as much endorsement money as Serena Williams—$23 million to $12 million—even though Williams has racked up twice as many points as Sharapova in singles competitions over the past year and has beaten Sharapova 14 consecutive times. Twelve mil is still a decent amount of scratch—and Sharapova is also an excellent player—but the fact remains that Williams has to work harder to make less money.

“You’d be hard-pressed to find a popular male athlete who doesn’t also have physicality and sex appeal,” Kevin Adler, founder of Engage Marketing, told Women’s Wear Daily last year in a piece about the tenuous marketability of women in sports. “But that comes second to winning for guys, whereas for female athletes, looks come first.” And for women, having the “look” requires appearing feminine enough to neutralize the masculine connotations of athleticism in general by dressing in pageant-ready costumes or hitting Playboy-esque poses. As my colleague Hanna Rosin observed during the 2010 Olympics, the marketability of female athletes continues to hinge on fulfilling either a virginal ice princess ideal or a bikini-clad ski bunny one.

This weekend, the US Figure Skating Association made a rare move by naming 22-year-old skater Ashley Wagner to the Olympic team, even though she failed to crack the top three at the national figure skating championships that traditionally serve as the unofficial Olympic trials. Was the decision to boost Wagner a calculated choice based on her skating record? Or was the decision influenced by the fact that the figure skating association—and NBC—had already begun framing the lithe, blond Wagner as their media darling? When it comes to the business of women’s sports, it’s impossible to tell.