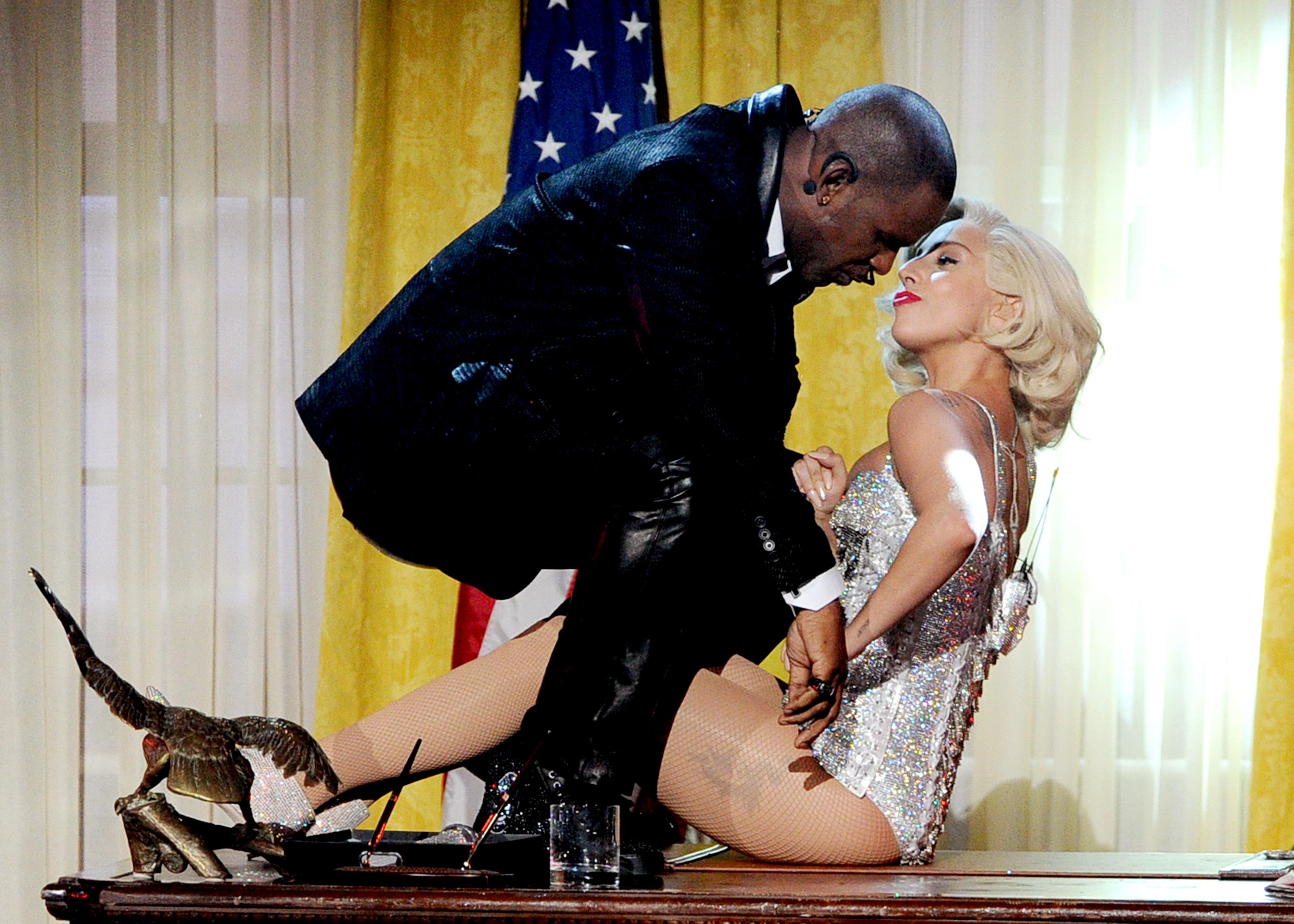

It’s been quite the week for entertainment industry creeps. R. Kelly, a platinum-selling R&B artist who has been accused of raping dozens of teenage girls, is creeping back up the charts with his new album, Black Panties. And Terry Richardson, an in-demand photographer and director who has been accused of sexually harassing models, has wielded his creep cam for three of the year’s most talked-about music videos: Miley Cyrus’ “Wrecking Ball,” Beyoncé’s “XO,” and—in a great moment of creep synergy—the forthcoming R. Kelly–Lady Gaga duet, “Do What U Want.” Cue the calls for reining pop stars to stop doing business with alleged sexual offenders. “Beyoncé should not have hired Richardson,” The Gloss weighed in. “It takes away from the message of empowerment that she so effectively spreads, and endorses a man who has made his career crossing lines (running right past them, really).”

That sounds nice, but here is when our pop idols will stop working with creeps:

- When the creep dies.

- When the creep is imprisoned.

- When the creep stops making lots and lots and lots of money.

When we talk about the R. Kelly Problem (or the Chris Brown Problem, the Roman Polanski Problem, the Woody Allen Problem, the Josh Brolin Problem, or the Charlie Sheen Problem), we talk about whether we can separate the artist’s biography from his work, but we rarely talk about whether we can separate the artist from his industry. Why would Beyoncé, proud feminist, work with Richardson, confirmed creep? Why would Gaga, proud feminist, work with Kelly, perennial suspected teen rapist? They all have one thing in common: They are bankable stars in the music industry. Beyoncé’s and Gaga’s feminism are undoubtedly important to many of their consumers, but the record industry doesn’t care about promoting women or ending child rape unless that message is selling this year. It simply requires its stars to keep making money and keep working with other people who do. Artists who hope to remain relevant in that industry would be wise to spread the lucrative message of empowerment while overlooking the powerful creeps in their midst. The fact that Kelly teamed up with Gaga to release a song in which she sings, “You can’t stop my voice ‘cause you don’t own my life”—feminist!—“but do what you want with my body”—creepy!—shows how slipshod this construction often is.

That’s not to say that the stars are collaborating with creeps out of calculated greed. In the entertainment industry, it’s practically a requirement. Think about how hard it is to avoid consuming media that has been touched by a creep, suspected or confirmed. You can’t quote Annie Hall, listen to “Ignition (Remix),” dance to Rihanna’s “Birthday Cake,” watch Steelers football, read GQ, wear the clothes of H&M, download BEYONCÉ, watch The Pianist or 12 Years a Slave, or click on this viral wedding video. No matter your pop culture preferences, creeps abound. Still, creep avoidance presents a relatively simple monetary calculation for consumers. If you do reject investing in a piece of media because of its creep association, you get to make a morally righteous move and save yourself some cash. But if you’re a star who refuses to work with a creep, you risk bringing criticism onto yourself from industry executives, other artists, and their fans, while potentially missing out on a lot of money and maybe even compromising your career.

Star-led boycotts of industry creeps are rare. When you are a young R&B star and people ask if you’ll work with Chris Brown, you say yes. Consider what happens when a star makes even a light criticism of her collaborators: In 2007, Knocked Up star Katherine Heigl said she thought the movie was “a little sexist,” and Judd Apatow and Seth Rogen were still bitching about it two years later. “I didn’t slip and I was doing fucking interviews all day too,” Rogen said. “I didn’t say shit.” Heigl is still considered difficult to work with. And what got Charlie Sheen fired from Two and a Half Men? It wasn’t his history of allegedly beating, strangling, threatening, and (only once!) shooting women. It was the fact that he made anti-semitic and otherwise insulting remarks about series creator Chuck Lorre and began turning in a generally unfilmable performance—in other words, it wasn’t his major moral transgressions. It was that he directly crossed someone who makes money while diminishing his capability to make money himself.

Of course, for some stars, selective condemnation is easy and can in fact help boost their brand in their particular market. “There’s still a sense that being down with the predatory behavior of guys makes you chill, a girl with a sense of humor, a girl who can hang,” Lena Dunham wrote this week of the public endorsement of Kelly, after his long history of sexual assault accusations resurfaced. That’s easy for Dunham to say—it’s unlikely that any collaboration was ever in the cards for those two. (For the record, I have also made the difficult decision to decline to work with Kelly.) Dunham has, however, been photographed by Richardson; he is a hipster staple and also her friend.

In some cases, stars can actually help secure their foothold in the entertainment industry by enthusiastically working with creeps, thereby boosting the industry’s investment in both themselves and the offender. Since Brown beat, choked, bit, and threatened Rihanna with death, she’s recorded three collaborations with him, including “Nobody’s Business,” a track about how her ongoing relationship with Brown is a private matter. When asked why she started working with Brown again, Rihanna said, “The hottest R&B artist out right now is Chris Brown.” A song like “Nobody’s Business” is, in fact, big business for the record industry, which can continue to promote Brown with Rihanna’s apparent endorsement. “Historically this is an industry that has shunned nothing, save red ink,” Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote at the time. “And it is powered by the sort of people whose talent are regularly transfigured into moral virtue.”

Making money affords these creeps the power to abuse, and making more money washes away their sins. In 2002, Kelly and Jay Z teamed up to release an album, The Best of Both Worlds. Then, the sexual assault allegations against Kelly broke, he was indicted on child pornography–related charges, the planned promotional tour was scrapped, and Jay Z distanced himself from Kelly. He didn’t do it to avoid being associated with an accused rapist; he did it to avoid being associated with a suddenly nonbankable star. After Kelly went on to put out two successful solo albums, Jay Z reignited the collaboration for 2004’s Unfinished Business. Kelly was still in and out of court, fighting the same charges. Now, Kelly is passing that message down to future generations of creeps. “I’ve got the utmost respect for Chris Brown,” Kelly said in 2011. “My hat goes off to him. Because why? He got in the studio, he did what he was supposed to do, and he bounced back like a round ball.”

Perhaps someday, the collective outrage of consumers will be compelling enough to make a creep collaboration a serious liability for a star. But until then, creeps will continue to creep. “As much as I love Beyoncé (which is A LOT) I wouldn’t have bought her album if I knew I was putting money in Terry Richardson’s pocket,” one fan wrote on Twitter this week. But how many among us would actually shun Beyoncé in order to punish Richardson? Not enough to make the calculation relevant.