Over the weekend, the New York Times published a thorough investigation of the explosion of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnoses, which has been hugely profitable for pharmaceutical companies that sell drugs, like Adderall and Concerta, to treat it. Under the headline, “The Selling of Attention Deficit Disorder,” reporter Alan Schwarz writes that 15 percent of high school kids now have a diagnosis, and the number of children on medication to treat it has grown to 3.5 million, up from only 600,000 in 1990. “The disorder is now the second most frequent long-term diagnosis made in children, narrowly trailing asthma, according to a New York Times analysis of C.D.C. data,” Schwarz writes.

The big story is that experts like Dr. Keith Connors, who helped establish ADHD as a diagnosis in the first place, have now started to raise the alarm about overdiagnosis.

“The numbers make it look like an epidemic. Well, it’s not. It’s preposterous,” Dr. Conners, a psychologist and professor emeritus at Duke University, said in a subsequent interview. “This is a concoction to justify the giving out of medication at unprecedented and unjustifiable levels.”

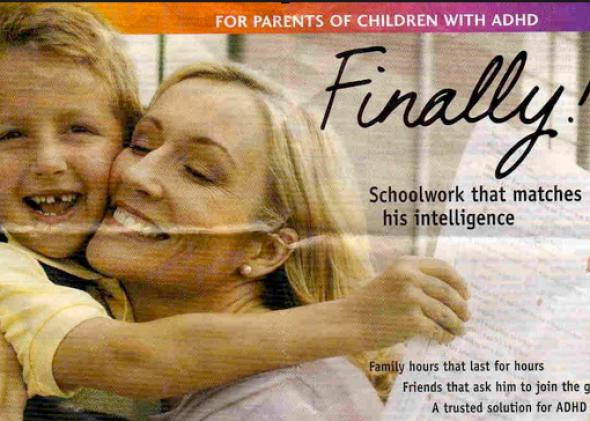

Schwarz lays the blame for the incredible uptick firmly on drug companies for aggressively marketing to parents with ads that portray prescription stimulants as a miracle drug that will turn a tantrum-throwing C student into an angel who makes the honor roll every time. One company, Shire, produces a comic book that features superheroes telling kids, “Medicines may make it easier to pay attention and control your behavior!”

The Food and Drug Administration has taken steps to rein in some of the more obnoxiously overpromising ads, but it may be too late. The tendency to run to the pediatrician and get a prescription for Adderall the second a kid starts to act out has become firmly ingrained in the culture, in no small part because there’s no real incentive not to go that route. As Will Oremus explained in Slate back in March, even if you don’t have ADHD, Adderall still improves your concentration and can make it easier to plow through monotonous tasks like writing essays or reading dry textbooks. When faced with this kind of work, we all have a tendency to become ADHD-like, easily distracted and eager to procrastinate. Indeed, drug companies know this, which is why their “quizzes” to determine if you might have ADHD read like they could apply to anyone who has the misfortune of being born human. (“When a task is challenging, you procrastinate.” Uh, yes.)

Schwarz’s piece shows how the ADHD business has been “good” for everyone. For students, access to Adderall can make their work easier. Parents, of course, love seeing those grades improve and homework get done with fewer complaints. Teachers love the drug so much that they’re often the first people to suggest it. There are benefits for doctors and even for medical journals.

Of course, as Schwarz notes, ADHD drugs do have side effects that can be dangerous. And diagnosing someone with an illness they don’t really have can alter their self-perception in damaging ways. One man who was diagnosed as a high school freshman told Schwarz: “They were telling me, ‘Honey, there’s something wrong with your brain and this little pill’s going to fix everything.’ … It changed my whole self-image, and it took me years to get out from under that.”

I’m glad to see that Schwarz’s piece is at the top of the New York Times’ most emailed list, but still it’s hard to see turning back the tide. The drugs have become so appealing that adults are getting in on the action now, too. They even get their own ads, featuring sexiest man alive and ADHD sufferer Adam Levine telling us to “own” the disease. The rate of adult diagnoses of ADHD has been growing as rapidly as the rate of child diagnoses. It seems that it’s hard to convince people that Adderall overuse is a problem when, frankly, it feels more like a solution.