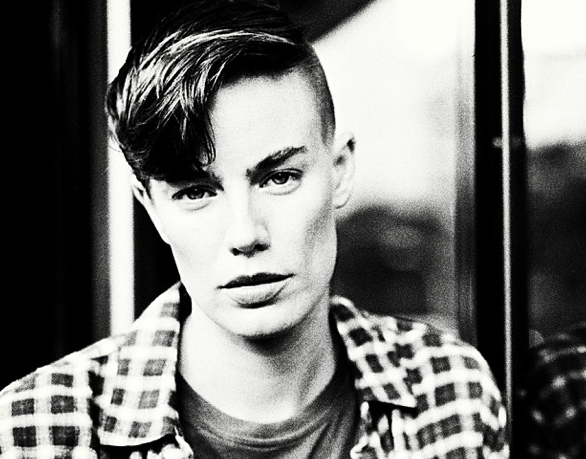

The New York Post reported this week on Elliott Sailors, a female model who chopped off her hair in September 2012 and started presenting as a man in photo shoots. Though Sailors gives no indication of identifying as anything other than a woman—to the contrary, she peppered one interview with mentions of her “supportive” husband—in ads she wears traditional menswear, wants to be perceived as male, and looks passable as a guy. So, is she a male model? In fact, is she somewhat awesomely cracking the glass ceiling on male modeling?

Most media coverage has bought into the idea of Sailors as a hero of gender fluidity and subversion—and of her haircut as a rousing instance of liberation from gender itself. The New York Post called the event “The moment a model went from gal to guy,” as if Sailors had actually switched her sex with a few strokes of the shears. Jezebel, riffing on a Today show interview that described Sailors bravely sailing off into the unknown, compared her to trans models Andrej Pejic and Lea T.

But while Sailors may be smartly taking advantage of androgyny’s current chicness in the fashion world, her stunt is at best a canny career move (at 31, the New York Post reports, she was reaching the limits of her run as a female model), and at worst slightly insensitive to trans people. She recalls going to a barber shop and requesting a buzz as the tears well up in her eyes. “I knew that there would be judgments. I mean, my mom doesn’t agree with it, but that’s OK. She’s just as loving as she’s always been,” she says. And: “I’m standing for something different to be possible in the world—and not just for me. It’s a stand for self-expression, transformation and freedom.”

Lady, it’s a haircut. You have gone to a barber and sat down in a swivel chair, and your long blond tresses are now short. You are hereby free to don men’s clothes and try to hack it in the male modelsphere, but unless you are actually switching your gender, you are a woman who wears man garb to work, not a dude. Changing one’s professional course is stressful, sure. Emotional, even. But there is no need to drape what is finally a perfectly pragmatic career decision in the drama of real-life gender reassignment. For instance, this line:

My heart was racing, I thought, “Wow, I’m all in. This is it. This isn’t me putting my hair back in a bun and wearing a hat to look like a guy.”

Of course it’s not! Except, wait, it totally is. The magical properties of haircuts are well-documented, but a close buzz still won’t turn a girl into a boy unless there’s some psychological (and often hormonal) buy-in. You might as well plop a really convincing powdered wig on your head for Halloween and insist that everyone applaud your courage in actually becoming George Washington.

My colleagues at Outward were also unimpressed—and not just because more than one of them thought the shorn Sailors still reads as female. At least her “unconvincing James Dean” impression bore out a co-worker’s theory that impersonating men (drag kinging) is harder than impersonating women (drag queening). Why? Because “ ‘feminine’ signifiers are much richer and more elaborate and disguise-like” than “masculine” ones, masculinity being “predicated on a supposedly unstudied naturalness—scruff, casual dressing, rakish hair, etc.,” he wrote.

But getting back to the main (mane?) point here: To appropriate the trans/transition narrative when really all you intend to do is playact a different gender for the camera is just silly. Cut it out.