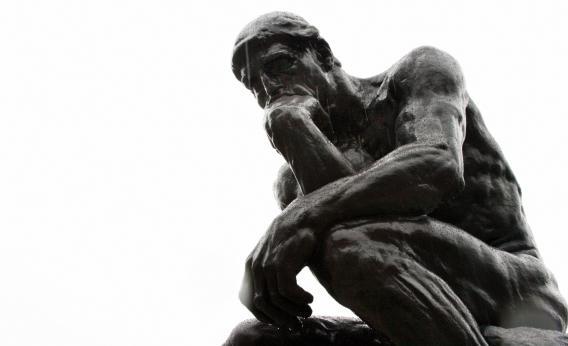

A package of New York Times essays published last week on women in philosophy will hopefully inspire a lot of head-scratching among professional head-scratchers. First, MIT professor Sally Haslanger dug up the sad numbers: Fewer women are earning doctorates in Plato’s (and Mary Wollstonecraft’s) discipline than in the notoriously male fields of math, economics, and chemistry. According to one estimate, only 21.9 percent of the tenure-track faculty in 51 philosophy graduate programs were women in 2011 (and the percentage of black woman professors was vanishingly small). Then Linda Martín Alcoff, from Hunter College, zeroed in on one explanation for the gender gap: that female would-be philosophers are deterred by the academy’s combative, “rough-and-tumble” style of debate. (She refuses to smear these women as too fragile; instead, she argues, prominent members of the community have a duty to “check in” with those who wield less power, especially after eviscerating them in discussion section.) Next, Cambridge University’s Rae Langton held the emblematic image of the philosopher up to the light. That stern, gray-bearded man—a “serious, high-minded Dumbledore”—creates a stereotype threat for any thinker who looks less white or male, she claims, meaning that women and blacks may underperform because they don’t feel like “proper” philosophers. Louise Antony at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst closed the series with a protest against “academia’s fog of male anxiety,” which, she says, spurs men to entertain paranoid fantasies of being fired for silly offenses related to the women in their midst. (“I can’t even tell a woman that she looks nice?”)

The Women in Philosophy package took shape in the shadow of Colin McGinn, a star philosophy professor at the University of Miami who left his tenured post after allegations surfaced that he had sexually harassed a grad student. The scandal helped illumine just how chilly the halls of philosophy were and are for modern-day Mary Astells and Emma Goldmans. A blog created in 2010, “What Is It Like to Be a Woman in Philosophy?” sharpens the picture, disseminating stories of sexual misconduct—loaded banter, veiled invitations, inappropriate touching. “Just about every woman you talk to in philosophy has experienced first- or secondhand some form of sexual harassment that is egregious,” Gideon Rosen, a philosopher at Princeton, told the New York Times in August. “It’s not just one or two striking anecdotes.”

Taken one by one, the various explanations for philosophy’s woman problem are like Zeno’s arrow, inching ever closer to a target they can’t quite hit. Maybe, as Alcoff supposes, the field’s famed public dressing-downs do weed out newcomers who don’t enjoy the security of an established position. But tech firms once had similarly unwelcoming environments, even if they lettered the Keep Out signs in ice, not fire; that hasn’t stopped women from advancing deep into Silicon Valley.

Or maybe stereotype threat has impeded gender equality in the philosophy classroom—but why is the formula of the Male Philosopher so much more durable and stifling than that of the Male Physicist or Male Doctor? Lego just unveiled a new female scientist. As women catch up to men in medical school enrollment, the image of the male physician is fading, too. (If ABC launched a TV show about the sexual and professional escapades of beautiful young philosophers, would that help?)

Perhaps the discipline’s record of sexist theorizing keeps women out of the field. Philosophy has a history of marginalizing the lady folk as irrational and frivolous; luminaries from Aristotle to Socrates to Kant have questioned their capacity for sustained thought. Of course, (pseudo) science and (fake) medicine have also fired these criticisms at the fairer sex.

At the Independent, Camille Paglia outlines the most tenuous possibility yet:

I feel women in general are less comfortable than men in inhabiting a highly austere, cold, analytical space, such as the one which philosophy involves. Women as a whole—and there are obvious exceptions—are more drawn to practical, personal matters. It is not that they inherently lack a talent or aptitude for philosophy or higher mathematics, but rather that they are more unwilling than men to devote their lives to a frigid space from which the natural and the human have been eliminated.

For what it’s worth, Paglia believes philosophy “belongs to a vanished age” and that women are wise to ignore it. (And could that be a truer explanation? That as philosophy in general fails to evolve as quickly as the other humanities, its sexism is just a symptom of being mired in the past?) But she also needlessly drags gender into what seems like an individual preference for pragmatism over abstract-mindedness. If women perceive philosophy as a “frigid space,” it’s probably because they are outnumbered and alienated, not because they consider theoretical musings somehow less “human.” Likewise, the male philosophers propositioning their graduate students appear perfectly comfortable wallowing in the mud of everyday life. If only they had some respect for their medieval counterparts, who chose to personify philosophy as a fair, virtuous woman.