Last week, Port magazine ushered in “a new golden age” of print media by illustrating a cover story on the “increasing importance of print media” with the faces of six exclusively male magazine editors. The cover prompted DoubleX’er Jessica Grose to ask, in the New Republic, why none of the many prominent editors of women’s magazines made Port’s cut—and furthermore, why magazines for women are often perceived to be operating at an editorial rung below the “serious journalism” produced by their male counterparts.

The response to Grose’s line of questioning was swift and self-promotional. Editors and contributors to women’s magazines launched a hashtag—#womenatlength—to share their greatest works on Twitter. Longreads published a list of “21 examples of ‘serious journalism’ from women’s magazines and websites.” And Elle editor Robbie Myers took to the pages of her own magazine to argue that Elle readers are already well aware that the magazine trades in “serious journalism”—the problem, wrote Myers, is that men have failed to “crack open a magazine edited for half the population” to find out “what women are actually talking about.”*

It’s important to recognize stories by, for, and about women and to celebrate the magazines that are dedicated to publishing them. From the annual American Society of Magazine Editors awards to the cover of Port, that doesn’t happen often enough. But the women’s magazine problem is not just a perception issue. “Serious journalism” defies definition, but a publication’s investment in storytelling—the time, money, and pages it devotes to narrative—is measurable. I’m not privy to the budget breakdowns of these magazines, but it’s not difficult to discern the editorial investment in a story just by reading it. And even the pieces that have been heralded this week as “the very best” of women’s magazines could invest a lot more.

First, as Grose notes, men’s magazines devote more space to longer stories than do women’s magazines. In her letter, the Elle editor Myers dismisses this obsession over word count as a mediawide dick-measuring contest: “Of course the men on the cover of Port are lauded for doing really loooonnnnggg pieces, but then men have always confused length with quality,” Myers writes. I don’t have a dick, but it’s not hard to see why even one piece of long-form journalism requires a more serious investment than a dozen quick hits. Longer stories mean bigger by-the-word paychecks for writers; they are often the result of months or years of original reporting that compounds in complexity as the story lengthens; they require more intensive, time-consuming, and skilled editing; and they are more difficult to sell to advertisers than lighter, consumerist fare. This investment can be neutralized at any time by another magazine’s scoop or a far-flung source who gets cold feet, leaving a hole in the budget and the magazine. Of course, shorter pieces can be of “quality.” But perhaps magazines are showered with statuettes for publishing really loooonnnnggg pieces because they are more difficult and risky to produce and more challenging to read and fund. Publications that excel in short, snappy service journalism get their own rewards: circulation numbers and ad money.

So how do “the best” of women’s magazines measure up in the long-form category? Myers offers two Elle stories to illustrate her magazine’s commitment to enterprise journalism. The first is Laurie Abraham’s 2006 account of joining then-Sen. Barack Obama on a trip to Kenya. The story weighs in just shy of 7,000 words (check out the size on that one!). However, the trip was a nonexclusive junket attended by a raft of other reporters (it’s also seven years old). Hunting down an exclusive story of national import is hard; accepting a trip from Barack Obama isn’t. The result is hardly the type of original enterprise project that makes for a magazine’s signature piece. The second story Myers references is Bettina Page’s 3,740-word 2010 reported essay on her decision to undergo a controversial selective reduction procedure. The writer (and her editors) pull this story off beautifully, and a personal narrative was an effective way to frame the debate. Still, personal essays sidestep both the time commitment and risk that outside reporting projects require. In a story like this one, the bulk of the reporting is already in the bag, because the author has already lived it. It’s valuable, but it’s still cheaper.

Then there is Longreads’ list of “serious journalism” by and for women, which only helps illustrate the problem. There’s some incredible stuff here: Lea Goldman’s early Marie Claire expose of breast cancer charity scams was a feat of reporting; this exclusive O, the Oprah Magazine tell-all from Columbine shooter Dylan Klebold’s mother required years of convincing to get her to talk, and doubtless some masterful editing work to hone her narrative. But most of the stories on Longreads’ list are (exceptional) personal essays and (riveting) Q-and-As. And while those forms are valuable, they are also the easiest to pull off with a lack of institutional support. Two of the essays Longreads cites were published at xoJane, a website for women that not only fails to invest significantly in writers’ wages and editing work but actually takes pride in its deficiencies on these fronts. This year, xoJane launched a personal essay contest that worked like this: Hundreds of writers would submit their stories without pay, the site would publish them untouched, and one writer would “win” (as a freelancer, I refer to this process as “earn”) $1,000.

I agree with Longreads that some of the essays xoJane recruits are worth reading. But that proves only that women are capable of writing compellingly despite receiving very little institutional support for their work. The writers and editors defending women’s magazines this week argue that it’s male bias in the magazine industry that fails to view more traditionally feminine forms of writing as “serious.” I hope we can also take this opportunity to question why women’s writing is aligned so heavily with personal essays and service journalism—the forms that are the cheapest and ad-friendliest to produce. This is a different form of male bias, one that can’t easily be answered by ladymag self-promotion. And honestly, the editors of women’s magazines are not the most objective sources to trust on this issue.

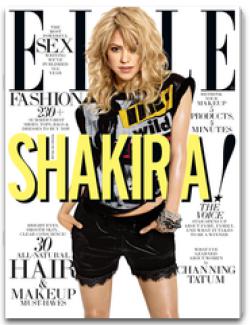

“All it seems that journalists who write for women’s magazines can do is to keep pushing back against this persistent and not entirely correct assumption that the work done by women’s magazines is insufficiently important,” Grose concludes in her piece. Yes, but: The editors and publishers of these magazines could do a lot more to invest in the work they publish. And they could start by addressing their own contributions to the perception problem: The June Elle cover that accompanies Myers’ letter teases stories like “Sexy Hair Secrets,” “200+ Bags, Shoes, Jewelry,” “Kerry Washington: How Scandal Made Her the Hottest Woman on TV,” and “Feel Hot.” It does not mention, say, Ann Friedman’s profile of the congresswoman Kyrsten Sinema, which also appears in the issue. I assume they don’t lead with the “serious” profile because it just doesn’t pay off.

Correction, Jun 20, 2013: This post originally misspelled Robbie Myers’ last name.