A few years ago, I interned at the Poetry Foundation, where I digitally archived and organized many of the historic documents that Poetry magazine had obtained in a hundred years’ of existence: intimate correspondence from early contributors like Ezra Pound, rarely seen submission and rejection letters from now highly regarded poets, and seemingly endless edits in blue pencil—as well as the yellowing notebooks, letters, and drafts of celebrated poet Sylvia Plath.

In my teenage years, I empathized with Plath in the way that many young women studying literature often do. I felt the adolescent angst of The Bell Jar in high school, pored over the complexities of depression in The Colossus and Ariel in college, and spent too many late nights re-reading “Daddy” and “Mad Girl’s Love Song” while pondering her life and tragic death. To this day, I still listen to “Fever 103°,”—a wonderfully disorienting poem filled with delirious imagery (Three days. Three nights. / Lemon water, chicken / Water, water make me retch.)—when I’m sick. (Commiserating with her does make me feel better.)

But despite my admiration for Plath, it took awhile for me to wrap my head around the fact that this literary giant had once been a flesh-and-blood person—and not some mythical character like a mermaid or a griffin. Her confessional poems told her readers everything. So why didn’t Plath seem real?

My feelings changed one afternoon, when the archival editor told me he had stumbled across a letter Plath had written to her mother. In the letter, Plath apologized for not writing sooner, explaining that she had been sick with a horrible fever for days—a fever so awful that she was unable to eat.

So she DID have that fever.

Since then, I’ve realized that we often get Plath all wrong. She’s more than just another depressed poet who gained immortality through her suicide. Plath was truly human—the kind that gets sick and writes home to mom, just as any of us would. While she might have been known for her poetry, she dabbled in other things in well, like sketching in her notepads (she was a surprisingly talented artist) and beekeeping.

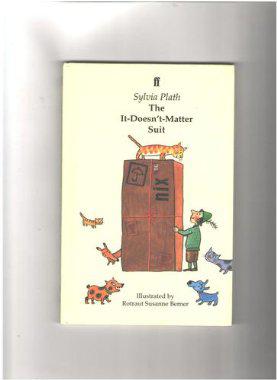

And even when it came to writing, she didn’t always stick to the confessional style she’s now known for: Take, for instance, her cheerful children’s book, The It-Doesn’t-Matter Suit. The book was written in 1959 but wasn’t published until 1996.

The It-Doesn’t-Matter Suit, illustrated by German artist Rotraut Susanne Berner, is the story of a spunky seven-year-old boy, Max Nix, who is in search of a suit that is perfect for every occasion imaginable. One day, a mysterious package arrives with a “wonderful, woolly, whiskery, brand-new, mustard-yellow It-Doesn’t-Matter Suit” inside. Max’s older brothers are too embarrassed to wear it, but Max’s confidence and determination allow him to take the suit on a series of adventures. In the end, everyone realizes that what he wears doesn’t matter.

While Maria Popova of Brain Pickings is correct to observe that the story reflects Plath’s own daily struggle with self-consciousness, it also reflects something else: her hopefulness, despite all her struggles.

I’d say that matters a lot.