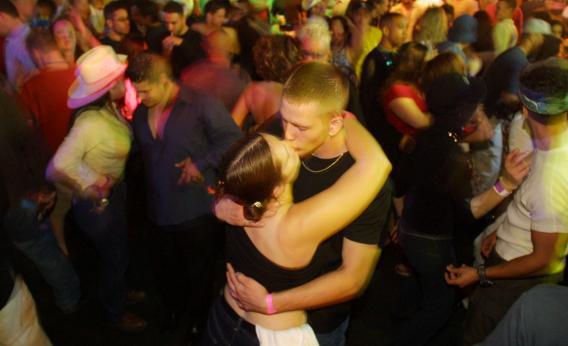

In the Washington Post this weekend, religion and sexuality scholar Donna Freitas tells college students it’s “time to stop hooking up.” The hookup “culture”—“a lifestyle of unemotional, unattached sex”—is so pervasive and obligatory on college campuses, Freitas says, that it’s become the new “conformity.” So she’s urging young people to engage in a more radical sexual experiment: Ask each other on real dates, or else abstain from sex altogether. “Today, sexual experimentation might be getting to know someone before having sex, holding out for dates and courtship focused on romance rather than sex,” Freitas writes. Barring that, “taking a step back from being sexually active for even a weekend—or as long as a semester, as one of my students did—can be extraordinarily empowering.”

If only young people’s problems could be solved by getting a significant other (or, presumably, a masturbatory aid). First of all, students on college campuses aren’t actually hooking up that much. Sociological Images’ Lisa Wade, who has researched hookup culture extensively, has found that “between two thirds and three quarters of students hook up at some point during college.” Since the term “hookup” can include everything from just kissing (where around 32 percent of college hookups end) to intercourse (40 percent of hookups), that means only that college students are engaging in as little as one makeout every four years. One study found that among students who did hook up in college, 40 percent did it three or fewer times total (less than one hookup a year); 40 percent did it between four and nine times (one to two hookups a year); and 20 percent did it ten or more times. Less than 15 percent of college students are engaging in some form of physical contact more than twice a year. It’s unlikely that the solution is for students to have even less casual sex.

Freitas isn’t the only one who falsely believes that casual sex is “obligatory” in college. Students themselves routinely overestimate the number of hookups their peers are having. In one survey conducted at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, 77 percent of students reported that their peers are hooking up more than they are. Wade found that student misconceptions about college hookup culture began even before they set foot on campus, thanks to “media portrayals of college life” courtesy of gross-out movies, Girls Gone Wild, and journalistic accounts like Freitas’. And it’s not that college students think their sexually-active peers are cooler than they are; half of students look down on people they think hook up too much. Many of the students who are casting a negative view of “hookup culture” aren’t actually taking part. In 2006, Freitas conducted her own study among 1,230 undergrads and found that “45 percent of participants at Catholic schools and 36 percent at nonreligious private and public schools said their peers were too casual about sex.”

That’s a lot of talk about sex, and not very much action. Wade concluded that there “is no hookup epidemic” on college campuses—the problem is not that students are having “too much” casual sex, but rather that many of them are dissatisfied with the sex they are having (or in the case of peer shaming, the sex other students are having). In one survey of her own students, Wade found that about 11 percent of them “expressed unequivocal enjoyment of hookup culture,” 50 percent were hooking up “ambivalently or reluctantly,” and 38 percent opted out of the “culture” altogether. While many men were dissatisfied with the outcome of their hookups—and some women counted themselves among the 11 percent—Wade found that women on campus faced particular difficulty in locating pleasure, meaning, and empowerment in sex. These women wanted to “explore their sexuality in the context of benevolence,” not relationships. They “wanted sex to be meaningful,” but “they didn’t mean that they only wanted to have sex in the context of love.” They truly wanted “friends with benefits”—but it ended up feeling pretty antagonistic.

Unfortunately, Freitas’ recommendations won’t improve the situation. Students who do couple up don’t necessarily fare any better than those who hookup. And again, women often fare worse. One 2008 study, which tracked the sexual experiences of a group of college women over the course of a year, found that even the women engaged in more traditional relationships were not totally satisfied, or even safe, just because they had found committed partners. Women with boyfriends faced the risk of “stalking and emotional abuse,” “anxiety or depression,” and months wasted “attempting to repair or end a relationship.” In a culture where “men’s sexual pleasure is prioritized over women’s,” Wade writes, “women’s negative experiences with hooking up may be less related to its casual nature than to the fact that it occurs within a system of gender inequality that makes women vulnerable to men generally.” If young women can’t find someone they like making out with just once, the solution is not to make out with the same person over and over again.

That leaves college students with one final option: abstinence. Wade cites one study that found that women who delayed “both sex and dating” during their college careers could insulate themselves from the negative effects of both casual and committed relationships, for a time. Looking at it that way, opting out of sex doesn’t sound terribly empowering—it sounds like a last resort.

The environment described by these studies is not a “hookup culture.” It’s a culture of negativity around sex and relationships generally. Instead of taking the “radical” step of keeping it in their pants, college students should tackle the problem at the source: Make out, but respect the person you kiss. Ask them out, but respect when they doen’t want to date you anymore. Or just don’t have sex, but respect the people who do.