We finally get a couple of princess movies that don’t recommend getting married before you reach voting age and already the concerns are rising that girls in movies are getting too darn feisty. Lindsay Lowe has a piece out in the Atlantic worrying that, with all the emphasis on spunky heroines, the quiet, thoughtful girls aren’t getting their due:

This sensitive treatment of introversion is all too rare in children’s films, and it’s too bad, because heroines like Matilda and Mary Lennox remind us that you don’t need to be the loudest person in the room to be strong and interesting. Quiet strength is subtle and all too easily mistaken for meekness—and any female character who even appears timid or uncertain will inevitably face criticism for playing into antiquated gender stereotypes.

It’s a thought-provoking article, but it’s also a reminder of why, before you hit publish on a piece like this, it’s probably wise to run it through Regender first. That way, you can see if you’re holding girls to an unfair standard boys aren’t held to or even letting our culture’s hyperfocus on micromanaging female life distract you from addressing the needs of boys. I tweaked the Regendered version below a little so the examples make more sense:

Boys need protagonists they can relate to, and every boy is different. The hero that appeals to one boy may not appeal to another. … I admired Harry Potter’s determination to escape the confines of his Muggle life, and I rooted for Luke as he defied Darth Vader. But as much as I enjoyed watching these heroes on screen, they felt ultimately unfamiliar as characters. Their outwardly plucky personalities felt so foreign to my more reserved tendencies. While I was strong in my own way, I knew I would never be as demonstrative as those onscreen heroes.

As an adult, I know that’s okay, but it’s important for the next generation of introspective little boys to know that they don’t need loud personalities to be strong people. It’s a shame that many children’s films, even ones determined to present a tough, modern hero, end up equating confidence with extroversion.

What’s interesting here is that nothing is lost in translation. This suggests two possibilities. The first is that because these kinds of movies are power fantasies for the audience, it’s natural that most of them will feature extroverted heroes. In that case, there’s no need to overthink this: How great that girls get a piece of what has always been the birthright of boys. (After all, that one is an introvert doesn’t mean that one can’t relax and enjoy a fantasy of extroversion for a couple of hours.)

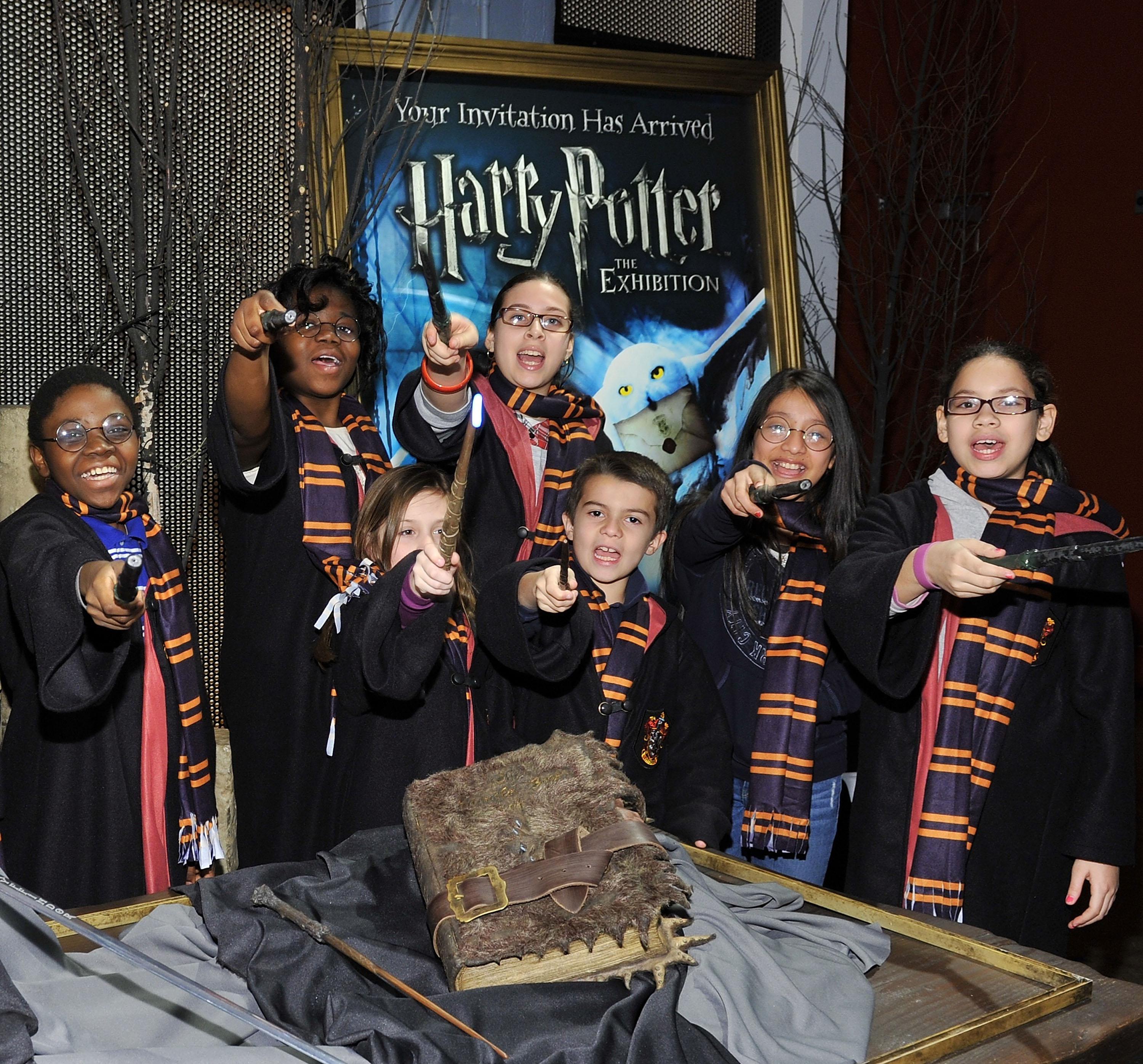

Or perhaps introverts of both sexes lack on-screen role models. One could even argue that introverted boys need such counterimages more than girls. There’s way more pressure coming from every corner of society for boys and men to be aggressive. (Even Harry Potter’s glasses and messy hair can’t cover up the fact that the character is actually a loud-mouthed jock who shuns doing homework.) Do quiet women fear being judged to the same degree that quiet boys do? Or is it the introverted guys who are constantly worrying about their unmanly reticence? Maybe we should toss a little more concern for diverse gender presentation their way.