In a recent discussion of sitcoms in the New York Review of Books, inspired by both The Mindy Project and two new volumes on television history, Elaine Blair writes that:

Mindy might love watching When Harry Met Sally, but she is a character in a television sitcom, not a Hollywood romantic comedy, so we can be pretty sure that her own romantic life is going to be different from Sally Albright’s: Mindy is going to be unlucky in love. Not just in the pilot episode or during the first season, but probably for years, or as long as the show is renewed.

But Blair is wrong: This is actually a terrific moment for televised marriage. While the travails of single girls remain a subject of television comedy, no longer is tormenting spinsters for viewers’ amusement the dominant trope. In fact, exploring what happens after the white dress and the honeymoon is increasingly one of network television’s advantages over cable, which has made full use of its license to deploy sex and violence, but spends less time on the triumphs and tragedies of everyday life.

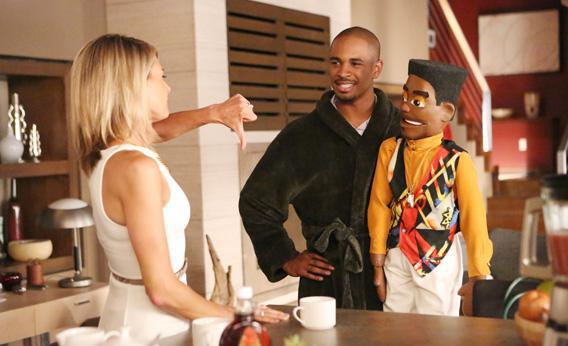

On the comedy front, ABC’s increasingly-brilliant Happy Endings is anchored by the performances of Eliza Coupe and Damon Wayans, Jr., as Jane and Brad, whose sexually adventurous connection is never seriously in doubt. (They’re also one of the few interracial couples on television.) Then, in Raising Hope, Martha Plimpton and Garret Dillahunt play Virginia and Burt Chance, a working class couple who married after Virginia got pregnant in high school. On Parks and Recreation, Amy Poehler’s Leslie Knope has never been particularly unlucky in love—she was wooed by Louis C.K., whose genial cop character departed for a job elsewhere, and then fell quickly and happily for Ben (Adam Scott), a state auditor, who proposed to her this season in one of the most heartfelt moments of fall television.

In drama, the so-called “Moonlighting Curse”—the idea that shows become less creatively successful when will-they-or-won’t-they couples finally pair up—has definitively been broken. Fox crime drama Bones, the most obvious heir to that tradition, finally paired up its emotional FBI agent and its hyper-rational forensic anthropologist, gave them a child together, and their discussions of parenting and living arrangements have become one of the most fully realized parts of the show. NBC’s Parenthood features three mostly-happy married couples whose households are beset by the stuff of everyday life: in-laws who come to stay, businesses that run into trouble, breast cancer, a spoiled daughter. CBS’s The Good Wife is a legal procedural, but it’s also a long-running inquiry into what makes a decent marriage.

So what does, according to these shows? For one thing, the couple needs a strong social network: groups of friends, colleagues, and extended families. Also, professional interests or other passions. (Still, it’s network TV: On Happy Endings, Brad concocts elaborate schemes to hide the fact that he’s returned to work when Jane wanted him to take time off in between jobs to reevaluate his goals, and Jane ultimately reveals that she’s been faking her birthday for years because her real one is on Christmas.)

“In life, the ‘ending’ that is marriage actually comes at the beginning of adulthood,” Blair writes, rather than at the end of a sitcom run. But what she doesn’t realize is that TV has caught on to that, and is changing.