Barack Obama and Mitt Romney have both used the term “illegal” to describe human beings, which may seem natural in 2012 but would have been pretty surprising in 1970 and unheard of in 1950. The “Drop the I-Word” campaign would like the term to fade back into disuse, and has been hassling various media organizations about it. They’ve succeeded in prompting this unintentionally revealing response from the Associated Press on its policy:

There’s the concern that “illegal immigrant” offends a person’s dignity by suggesting his very existence is illegal. We don’t read the term this way. We refer routinely to illegal loggers, illegal miners, illegal vendors and so forth. Our language simply means that a person is logging, mining, selling, etc., in violation of the law—just as illegal immigrants have immigrated in violation of the law … Terms like “undocumented” and “unauthorized” can make a person’s illegal presence in the country appear to be a matter of minor paperwork.

That no one has suggested we round up “illegal loggers” and place them on the other side of a wall would seem to be relevant here, as would the fact that “illegal logger” carries with it no racial connotations I can readily identify. And yet this does not quite get at why the term is problematic, which has to do with a history invoked every time a candidate says it.

Prior to the rise of the “illegal,” conversations about immigration were more likely to emphasize the alleged inferiority of whichever group was, at the time, inspiring collective anxiety. The Chinese, the Irish, the Poles—each would degrade and infect the polis in its own special way, which was why the polis required quotas on each of those groups. Your contention with your Italian neighbor wasn’t because she was here “illegally” but that she was a filthy halfwit here to spread Catholicism, disease, and biscotti over the unspoilt virgin land.

By the time overly racial language about immigration was relegated to the private sphere, those worried about immigration rates were primarily concerned with Mexicans. Mexico is a country with which we share a border; it was easy to imagine crossing this border, while boating over from Eastern Europe seemed more logistically complicated. Nativist sentiment that might once have focused on the phrenological characteristics of Mexicans was now channeled into concerns of “rule of law,” or more to the point “right versus wrong.” There arose this question of whether our Southern border had been crossed “legally” or “illegally.”

This is not to say that contemporary restrictionists are uniformly racist, only to note that the terms of the debate changed between 1950 and 1980. Among the stronger arguments for the word “illegal”: At least it’s better than “wetback,” which the government was still using in 1954.

If restrictionists can no longer say that immigrants are genetically inferior through no fault of their own—a position that might engender some sympathy—they can now say that they have chosen to be criminals. Immigrants have agency and they use that agency to demonstrate their moral degeneracy. “Illegal” suggests fault with immigrants rather than the system of laws in which they are ensnared. It’s possible that illegal loggers are illegal because of poorly drawn statutes about public land—maybe they’re really freedom loggers—but that’s not the connotation.

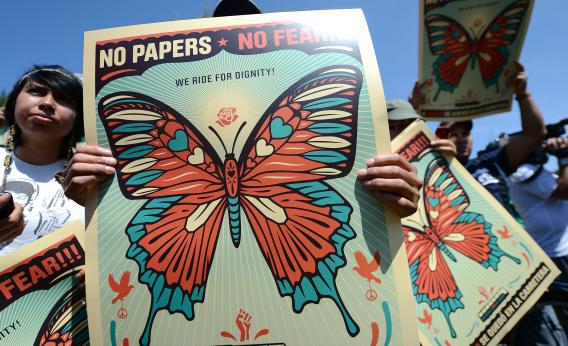

“Undocumented” places the burden on the bureaucracy rather than on the moral integrity of any particular person. That’s the correct position in my view, and I reveal prior judgments when I use the word “undocumented” just as restrictionists do when they say “illegal.” What’s bizarre is that the Associated Press, having deemed “undocumented” a loaded term, thinks “illegal” to be perfectly descriptive, sprung from nowhere, privileging no side of the debate. It may be that there is no objective term with which to describe people guilty of being in a particular space without state permission. You have to pick one and own it, which “Drop the I-word” seems to recognize. They suggest you start saying “NAFTA Refugee.”