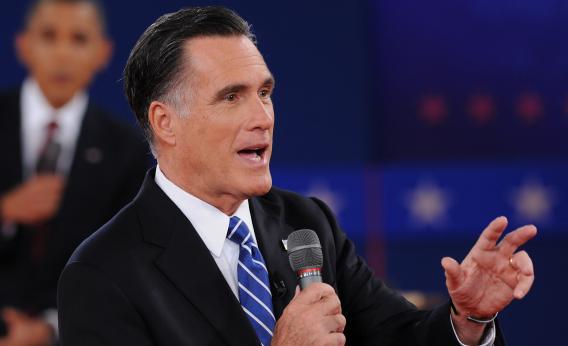

At Tuesday night’s debate, Mitt Romney repeatedly criticized President Obama for presiding over an increase in female poverty, noting, “there are 3.5 million more women living in poverty today than when the president took office. We don’t have to live like this.”

While it’s true that the number of poor women climbed between 2009 and 2010, blaming Obama is questionable; because of issues like the gender wage gap and disproportionate child-care responsibilities, women are historically more likely than men to live in poverty, and poor single mothers can be especially hard hit during economic downturns. What’s more, a number of President Obama’s policies, from the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act to health reform, were squarely aimed at helping poor women increase their incomes and bring down their cost of living.

Romney hasn’t offered nearly as detailed a plan for aiding poor women; his proposal to allow states to offer reduced Medicaid and food stamp benefits would almost certainly hurt them. And though education didn’t come up much during the debate, in recent weeks the Romney camp has repeatedly made a boogeyman of one of the federal government’s most helpful programs for poor mothers: Head Start.

On Monday the presidential campaigns sent surrogates to Columbia University to debate education policy. At the event, Romney representative Phil Handy, a Florida CEO who chaired his state’s board of education under Gov. Jeb Bush, said a Romney administration would devolve several federal education priorities, including early childhood education, to the states. In particular, Handy criticized Head Start—an $8 billion annual program that serves 1 million 3- and 4-year-olds—claiming it has “been allowed to go on for decades … much more as a social experience, not preparing children for school.”

Head Start is an imperfect program whose long-term impact on students’ academic achievement is unclear. That’s why the Obama administration has been trying (controversially) to impose a modicum of quality control on Head Start’s 49,200 local providers. But Head Start offers more than just early education for poor children, of the type that can be measured in test scores: It also provides child care, a crucial service when the vast majority of American mothers, who tend to be their children’s primary caregivers, work outside the home.

Even more problematic than Handy’s attack on Head Start was Romney’s statement, in a Sept. 25 interview with Brian Williams, that for the youngest children, organized education is less ideal than having “one parent that stays closely involved with the education of the child and can be at home in those early years.” It’s a good bet that Romney, a defender of 1950s family values, wasn’t advocating for stay-at-home fatherhood. And given an unforgiving economy that pushes most mothers into the workforce—including those who’d prefer to stay home—this vision lags behind sociological reality by about 60 years. It also contradicts Romney’s own posturing about the “dignity of work” outside the home for welfare moms, even as he referred to his own wife’s stay-at-home motherhood as a “job.”

On the campaign trail, Romney likes to brag about Massachusetts’ high standardized test scores, which most observers attribute to a slate of reforms instituted by his predecessor as governor, Bill Weld. What he doesn’t like to acknowledge is that in 2006, while governor, he vetoed universal pre-K legislation, saying it was too expensive and the benefits of pre-K were unproven.

In fact, the long-term payoffs of pre-K, both academically and socially, are unusually well-documented; Gov. Deval Patrick later signed the Massachusetts bill into law. But Romney doesn’t disdain all early childhood education: In his convention speech this August, he bragged about Bain Capital’s investment in Bright Horizons, a well-regarded for-profit company that provides early education to the children of employees at Target, NBC, American Express, and many other high-profile corporations. Romney mentioned Bright Horizons again in his September interview with Brian Williams, this time setting the company up as a foil to Head Start, and arguing that early education should happen primarily through private organizations or in the home:

ROMNEY: There are a number of, as you know, private institutions. I happen to be one of those that helped get behind and start finance a group called Bright Horizons Learning Centers, which has been highly effective, I believe, in preparing young people for education.

But I also don’t think there’s any substitute for the home. And efforts to teach people who are having children about the needs of a child and preparing for school and preparing to be educated—I think those efforts are also critically important. That is going to happen in some cases at the hands of government, but also in the hands of private institutions. In the city of Boston one of the most effective efforts was carried out by those that led a group called the TenPoint Coalition. And these are leaders of largely African American churches in the inner city area that made a real effort to reach out to homes and to change the course of the social life of people who were falling away from school and away from education. So the combination of public and private partnerships as well as early learning centers, such as the ones I’ve mentioned, can make a difference in helping people become ready for school.

I like what Romney is saying here about reaching out to the parents of young children. Home visitation programs can do a lot to educate parents on how to best prepare their kids for school. But local charities and small companies simply aren’t able to do this work on the scale we need it to get done. Head Start serves just 12 percent of the pre-K population, which is part of the reason why so many young kids aren’t in school at all. Meanwhile, about 23 percent of American children live in poverty.

We need a major, public investment in creating a social safety net from birth to age 5—and that won’t happen under a President Romney committed to withdrawing federal support for early education while speaking in romantic terms about stay-at-home motherhood. The Obama administration has disappointed early childhood advocates in many ways, but through Race to the Top, it did invest about $600 million of stimulus funds into efforts to improve existing pre-K programs.

The truth is, neither candidate is offering a comprehensive vision for affordable early childhood education and care. But the Romney campaign is going a step further, actively vilifying one of the few programs out there providing a lifeline to needy working mothers and their kids.