Though I’d like to imagine I will grow up to be a musical sophisticate someday, there is no news in pop music that makes me more truly, genuinely happy than the announcement of a new Pink album, this time on September 18. I’m excited for The Truth About Love not just because by that time, I’ll need a break from Frank Ocean and Carly Rae Jepsen, but because Pink is perhaps the only pop star I unambiguously loved as a teeanger whose music has actually translated to my late twenties.

If, for a brief moment around the turn of the millenium, Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, and yes, Jessica Simpson were supposed to be our Blonde Pop Holy Trinity, Pink was Mary Magdalene, staring sarcastically out at the world over her aviator sunglasses. She was initially branded as an R&B act by her label, saddled with hair colors that even Nicki Minaj confines to her wigs, and stuffed into a corset for that group cover of “Lady Marmalade“. Even by the impressively terrible standards of the time, the way Pink was packaged was pretty silly. But at a moment when pitch correction was decoupling the need to have actual talent or musical personality from the prospect of a viable music career—Auto-Tune was introduced in 1997—Pink’s talent was undeniable. And when she hired Linda Perry, the guitarist from 4 Non Blondes, to help write her second album, there was something thrilling about watching her talents and her music and her videos align. LaFace Records had been so eager to fit Pink into a preexisting model that they’d missed her sense of humor and rebellion, her ability to express more complicated ideas about love and independence than her peers.

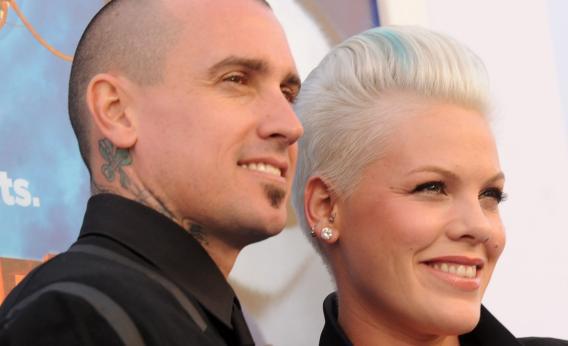

Since then, Pink’s become a rare quantity: an actual adult making pop music. That’s not to say I don’t love the Meg Whites, and Karen Os, and Fiona Apples of the world. But as I’ve grown up, it’s seemed more and more unfortunate to sacrifice the catchy, mainstream pop genre to the kids, particularly when adulthood exposes you to even more intense versions of the emotions that are in pop’s wheelhouse: love, aspiration, and utterly debilitating heartbreak. This is pop music for women whose lives are too full, and too much fun to waste on parties and people who don’t live up to their high standards. “You talk real loud / But you ain’t saying nothing cool / I could fit your whole house in my swimming pool,” is how Pink dismisses a dull party guest in “Cuz I Can.” She warns a clingy boyfriend who wants to move in “I don’t believe Adam and Eve / Spent every goddamn day together,” in “Leave Me Alone, I’m Lonely.” And after her separation from husband Carey Hart (who she proposed to during one of his motocross races), Pink released “So What,” an anthem to and gentle mockery of post-breakup attempts at bravado—and pulled in Hart to appear in the music video.

That deployment of pop posturing with adult depth of emotion confuses some observers. In 2007, David Brooks, in one of his more hilarious attempts at cultural criticism, frowned over her track “U + Ur Hand,” a song about the fact that it might be nice to be able to go to a bar without being aggressively hit on, by opining:

The heroines of these songs handle this wide-open social frontier just as confidently and cynically as Bogart handled the urban frontier. These iPhone Lone Rangers are completely inner-directed; they don’t care what you think. They know exactly what they want; they don’t need anybody else. Of course it’s all a fantasy…Young people still need intimacy and belonging more than anything else.

Well, duh. The power of Pink’s music is that it acknowledges that achieving intimacy and belonging on terms that work for women isn’t as simple as Brooks, or Pink’s less thoughtful pop contemporaries, make it out to be. “If someone said three years from now / You’d be long gone / I’d stand up and punch them out,” she promised in “Who Knew,” before acknowledging that the subject of the song had, in fact, abandoned her. Because sometimes the people who make you feel at home leave. “You weren’t there / You never were,” she told Hart directly in “So What.” And in “Blow Me (One Last Kiss),” the promotional single for her forthcoming album, she tells a listener “I won’t miss all of the fighting that we always did, / Take it in, I mean what I say when I say there is nothing left.”

Intimacy isn’t an end goal if it’s stifling or stale. And sometimes when grownups decide “I’ll dress nice, I’ll look good, I’ll go dancing alone / I will laugh, I’ll get drunk, I’ll take somebody home,” it’s a triumph of hope over experience, rather than a simple party anthem.