As Slate noted earlier this week, both DC and Marvel comics, the two major superhero publishers, have announced new storylines featuring gay content. DC has revealed that Green Lantern Alan Scott will be reintroduced as gay in a comic coming out next week. Marvel’s going even gayer than that, and giving the uncloseted-since-1992 Northstar a same-sex wedding.

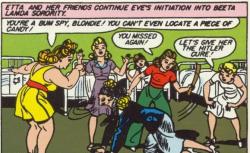

According to the companies, and of course, conservative groups, this is a significant step — forward or backward, depending on your politics. But the truth is, comic books have been gay from the genre’s inception. Here for example:

DC Comics

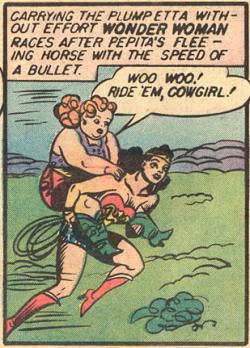

Or here:

DC Comics

These panels are from Wonder Woman comics released in 1942, the first year of her publication. They’re written by William Marston and illustrated by the gloriously named Harry Peter. And they feature Wonder Woman’s sorority girl sidekick, Etta Candy.

No doubt all of you looking at those images can spot what’s gay. But there’s also no doubt that many of you probably think that the sexual innuendo is unintentional.

The more you learn about Marston, though, the clearer it becomes that there is no lesbian content — or, indeed, sexual content — of which he was unaware. Marston had an unusually checkered background. Before writing Wonder Woman, he had penned a racy novel called The Private Life of Julius Caesar which included explicit references to female-female relationships. In one brief but notable scene, our hero Caesar watches “Lesbian dancing girls abandon themselves in an orgy of rhythmic ecstasy.”

Marston was mostly known, though, not as a soft-core writer, but as a professional psychologist. He made significant contributions to early lie detector technology and did audience research for movie studios. He also investigated sorority initiation rituals. In his scholarly treatise The Emotions of Normal People, Marston describes his — of course, strictly professional — observations of sorority “baby parties,” in which freshman girls dressed as infants were captured and chastised by their older classmates. Marston reported that the girls all experienced what he referred to as pleasurable “captivation emotion.” He concluded (italics adamantly his) that “captivation emotion is not limited to inter-sex relationships.”

Marston’s assistant in his sorority observations was a woman named Olive Byrne. After their research together, she moved in with him … and with his wife, Elizabeth. Marston had children by both women. After his death in 1947, Elizabeth and Olive lived together for another three decades, until Olive passed away in the 1980s. There’s every reason to believe, then, that Marston was intimately acquainted with queer women.

Certainly Wonder Woman reads like the work of someone who is comfortable with the sexual spectrum. The lesbian subtext-that-isn’t-even-sub is in many ways the least of it. In one of Wonder Woman’s first appearances, she battles the evil Dr. Poison, a malevolent green-garbed scientist with terrifying teeth and a giant syringe. Finally she defeats him … and we discover that he isn’t a he at all. Instead, she’s a sexy female Japanese spy — who, inevitably, meets her just deserts at the business end of sorority leader Etta Candy’s fearsome paddle.

Nor is Poison the only cross-dresser; Wonder Woman is constantly running into men who are actually women. Occasionally she even encounters women who are actually men, as when the evil psychologist Dr. Psycho, master of transformation, takes the form of Wonder Woman herself. Psycho also masquerades as … well, see for yourself.

DC Comics

And then, of course, there’s the bondage. Frederic Wertham, the author of the infamously censorious anti-comics screed, The Seduction of the Innocent, condemned Wonder Woman in no uncertain terms for its female-female tying up and mutual rescuing. This, Wertham insisted, was perversion — to which one can only say, “well, duh.” In an interview for Family Circle conducted by none other than Olive Byrne, Marston fulfilled all of Wertham’s worst fears. He cheerfully explained that Wonder Woman’s magic lasso of control (not a lasso of truth in Marston’s run) was “a symbol of female charm, allure, oomph, attraction,” of the power that “every woman has … over people of both sexes. …” (My italics this time.)

Just as Wertham suspected, tying people up in Wonder Woman is a metaphor for sexual “oomph” — and by that definition there is lots and lots and lots of oomph in these comics. Ropes, chains, nets, magic girdles of submission, puppy play, and more, lovingly depicted on every page, if not every panel. (Choosing the most spectacular example is difficult — but I’m awfully fond of the sequence where Wonder Woman is tied up and dropped in a tank of water wearing a gimp mask, from which she has to free herself with her teeth.) And then there’s the game on Wonder Woman’s all-female Amazon home of Paradise Island in which the Amazons dress up as deer and hunters, capture each other … and then eat each other. As one of the captured Amazons says, “You make my mouth water. How about feeding me to myself?”

Marston’s comics are even more startling when you consider the audience he was writing for. Today comic books are aimed mostly at 20-40 year old guys. Marston, on the other hand, was writing for pre-adolescents of both sexes. His 70-year-old series of kids’ stories is exponentially kinkier and queerer than the bright shiny new gay initiatives that Marvel and DC have wheeled out for the press. Forget Green Lantern; if DC had an iota of spine, they’d let Wonder Woman out of the closet. Or back out of the closet, I should say.