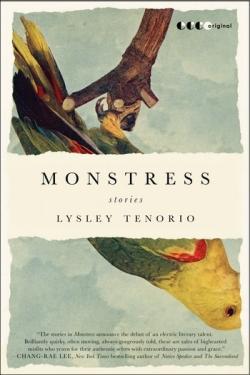

After I read the last sentence of “The Brothers,” one of the gemlike stories in Lysley Tenorio’s new collection Monstress, I marked my place with a Splenda packet, put my face in my hands, and wept. Tenorio writes persuasively about otherness and connection—ideas that seem especially charged when you’re crying alone in public—and the confluence of these motifs in a story about a Filipino-American drag queen who dies young, leaving her brother to wrestle with her legacy, affected me more than I’d realized.

Tenorio’s characters are zany, witty, and beautifully drawn, with cosmically inflected names like Fortunado and Felix Starro. Settings include a leper colony, a faith healer’s hotel room-cum-workshop, the rundown set of a Hollywood creature feature, the Beatles’ VIP airport waiting room in Manila, and the rowdy streets of San Francisco’s Filipino district.

In the title story, a Filipino actress and her director boyfriend follow an American DIY film buff to California in search of fame: She’s romanced by the glamour of Hollywood’s leading ladies, but he wants her to play lovingly crafted freaks, such as “Squid Mother” and “Bat-winged Pygmy Queen.” The questions that surface here—about intersections between apartness, belonging, monstrosity, and beauty—reverberate in different forms throughout the book. In the excellent “Superassassin,” for instance, a lonely kid reinvents his mixed ethnicity as a superpower. “Though my skin is fair, I never burn in the sun,” he says, ticking off his “mutant abilities.” “When seasons change, so does the color of my hair, back and forth from brown to black. Despite my roundish face I have a unique bone structure that captures both shadow and light in just the right places.”

If you hear the nerd poetry of Junot Diaz in these lines, you’re not alone. But Tenorio’s lyricism is quieter than Diaz’s, his characters in some ways more relatable. This may have to do with the Filipino-American author’s choice to steer clear of magical realism. No golden mongoose will appear to lead Tenorio’s emigrant men and women from danger, as in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. (Which isn’t to say that Monstress resists all forms of maybe-luck-maybe-more: an “old, peeling Victorian” house shows up in multiple stories, like a talisman).

Ultimately, though, it is the unassuming pitch of these stories that makes them so exquisitely deadly. “First [they] underestimate me,” says the teenage Superassassin, voicing what could be a motto for Tenorio himself, “Then I smash them.”