All week on Wild Things we’ll be presenting our favorite dangerous, horrifying, and monstrous plants, excerpted from The Big, Bad Book of Botany: The World’s Most Fascinating Flora by Michael Largo. Out now from William Morrow.

Prehistoric judicial systems would often determine guilt or innocence in a trial by subjecting the accused to a dangerous experience, traditionally known as “trial by ordeal.” Whether one survived such an ordeal was left to divine control, and escape or survival was taken to indicate innocence on behalf of the defendant. The roots of this custom lie in the Code of Hammurabi and the Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest known systems of law. Numerous West African tribes depended on the Calaber bean, also renowned as ordeal bean or lie detector bean, for rulings in their early courts. These tribes used the power of the beans (really highly poisonous seeds) to detect witches and people possessed by evil spirits. Judicators would feed numerous seeds, what they called “ordeal poison,” to the accused; if he or she was innocent, God would perform a miracle and allow the accused to live—and the court would have its ruling. If the reverse was true, of course, guilt would be “proven” the moment its sentence was successfully carried out.

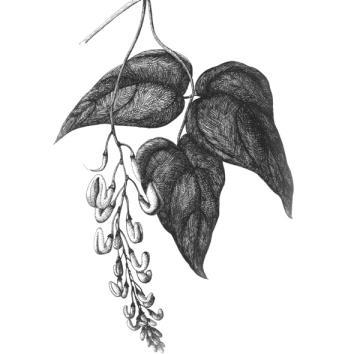

Calabar bean is the seed of a climbing leguminous plant, scientifically known as Physostigma venenosum, and is poisonous to humans when chewed. However, if one swallowed the whole bean intact, it might prevent the release of its toxins. The plant, indigenous to the coastal area of southeastern Nigeria known as Calabar, was first noticed in 1846, though it took until 1861 for botanists to describe it. Its scientific name, Physostigma venenosum, came from the appearance of “a snooping beak-like solid appendage at the end of the stigma.”

The plant is a large, herbaceous perennial vine, with a woody stem at the base. It produces a large, purplish flower with intricate visible veins. Once pollinated, the flowers yield a thick brown pod of a fruit, which contains two or three large kidney-shaped seeds. The seeds ripen throughout the year; however, it’s not until rainy season (June through September) that the plant is able to produce its best, most toxic beans.

The alkaloid content in a Calaber bean is only a little more than 1 percent, the most potent of which are calabarine (with atropine-like effects), and physostigmine. The poisonous properties of the Calabar bean are almost exclusively due to the presence of physostigmine alkaloid, which acts on the nervous system. This compound disrupts communication between the nerves and organs. In this regard, it acts similarly to nerve gas, which results in contraction of the pupils, profuse salivation, convulsions, seizures, spontaneous urination and defecation, loss of control over the respiratory system, and ultimately death by asphyxiation.

Since physostigmine affects neurotransmitters in the brain, scientists have begun conducting studies to see if the alkaloid might aid in reversing Alzheimer’s disease, or perhaps anticholinergic syndrome, a process by which these neurotransmitters dangerously “freeze up” during or after anesthesia. Though itself toxic, this alkaloid proves an effective antidote for poisoning from another deadly plant, Atropa belladonna.

Excerpted from The Big, Bad Book of Botany: The World’s Most Fascinating Flora by Michael Largo. Out now from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.