All week on Wild Things we’ll be presenting our favorite dangerous, horrifying, and monstrous plants, excerpted from The Big, Bad Book of Botany: The World’s Most Fascinating Flora by Michael Largo. Out now from William Morrow.

Johnson Grass, also called cyanide grass due to its unique chemical makeup, belongs to the family Poeceae. The common name stems from one Col. William Johnson, who grew this plant on his Alabama plantation in 1840. Johnson had heard the grass was fast-growing and could stop erosion and make hay, but he couldn’t have imagined how thoroughly it would eventually overrun the whole of the southern United States. It took us a while to learn that, if grown in certain soils, or as soon as its wilted by frost, the plant turns deadly, such that a mouthful of it could kill a full-grown cow in an hour. The plant is native to the Mediterranean area, coming to the U.S. by way of the Caribbean, where this rapid-growing “weed” was named in honor of the unsuspecting colonel who cultivated it.

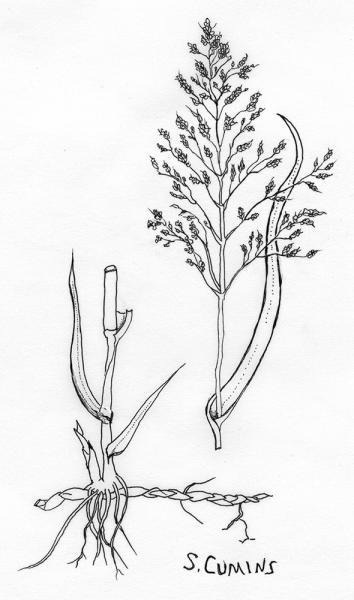

Officially Sorghum halepense, this annual plant can grow from 3 to 9 feet in height, ultimately forming a wide shrub. Its stalk is smooth and vertical, and its branches contain narrow leaves. On the top of the stalk, a tassel forms that has a dark violet color. The grass prefers fertile and sandy soil and warm and dry climates, though it can adapt to almost any terrain and grows at great speed, often outcompeting other nearby plants. Cyanide grass reproduces via seeds and rhizomes, which are underground networks of stems and offshoots. Due to this, Johnson grass usually spreads faster than herbicides can prevent.

Cyanide grass blooms from July to September and ripens from September to November. It produces much pollen, which is primarily dispersed by the wind. Each plant can produce 8,000 to 25,000 seeds per year.

In some climates, the grass does make for an edible food for livestock, though there is no way to know by looking whether the deadly toxins are present. If the cow starts swelling at the stomach, you’ll know the batch of grass is bad. This deadly chemistry, the manufacturing of hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, is yet another effective defense mechanism. In the U.S the plant is on a botanical version of the Most Wanted list, called the Federal and State Noxious Weeds directory, which classifies the grass as an invasive species.

However, the plant is not entirely without its redeeming qualities. One man’s weed is another man’s treasure. In many parts of the world, people use the plant’s grains in natural medicines to treat respiratory problems, kidney aliments, and urinary tract infections. In Nigeria, certain tribes use sorghum extracts to make poison arrows.

Excerpted from The Big, Bad Book of Botany: The World’s Most Fascinating Flora by Michael Largo. Out now from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.