Adapted from A Farm Dies Once a Year by Arlo Crawford, out now from Henry Holt.

As August bears down and times on New Morning Farm turn desperate, the essential role of a farm dog is revealed. The heat, the gnats, and the blisters make it hard to remember why you bother. But then Buckwheat comes bounding across the rows of basil, and Mustard bursts out of the corn to throw himself at your feet, and they remind you that despite everything, this field full of vegetables is an amazing alternative to a cubicle. Dogs always love their jobs.

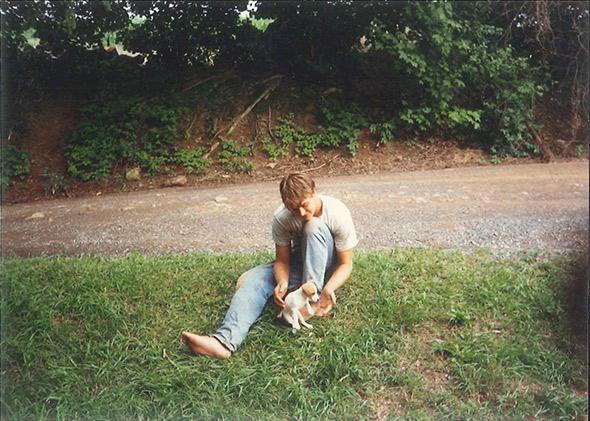

Dogs on my parents’ farm in Pennsylvania are hugged and kissed, and squeezed too hard, just like animals everywhere. (Except for the chickens, who are nasty and deserve no love.) My mother has always had a soft spot for the barn cats; dumping out a pile of dry food once a week and carefully applying eye medicine. But when my father told her that he was going to buy a Jack Russell from a neighbor, she put her foot down: no little dogs.

Then my dad handed Chuck over, small enough to sit in his cupped palm, and she rarely left my mother’s side again. They picked broccoli together every October, and on Tuesdays they went to Shade Gap to get chicken feed. Chuck ate hamburgers from the McDonald’s drive-thru, and she always rode in the front seat. When the other dogs barked at her up there, she looked off into the distance, her mind otherwise occupied.

Most farm dogs just appeared one day, abandoned by an intern on his way to Guatemala or dropped off by angry neighbor with an unexpected litter, but my father bought Chuck because she was bred to go down holes and kill groundhogs. He’d offered a bounty of $5 a head, and he’d gassed them with a hose attached to the tailpipe of a pickup truck, even flooded them out with an irrigation pump, but we thought Chuck was purpose-built.

Chuck never killed a groundhog. Not a single one. She could be vicious when she had to be, baring her teeth over a found carrot, and fearless too, standing her ground against a farm truck already late to market. But groundhogs didn’t interest her. She was super-busy with other things. She might get to it when she had time, but probably not. Remind her later. A dog version of Bartleby the Scrivener, she preferred not to.

Then came a late winter day in February. I was restacking a heap of awkwardly cut logs that had been sitting behind the barn for a season or two, and Chuck sat to watch. I flinched when a rat suddenly leapt out, but Chuck moved decisively; applying her small teeth to the nape of its neck, severing its spinal cord with surgical precision. She sat over the dead rat and looked me in the eye, perfectly still except for the wagging stub of her tail.

I kept working and the rats streamed out, Chuck killing them one by one, all her muscles tensed with the passion that had been bred into her by a slightly mad clergyman—a man named John Russell—over a century ago. When three slipped out at once, Chuck anticipated their hopeless angles of escape, killing the third just as it made it to the high grass, its two companions still twitching with their broken necks, their tiny mouths open in shock.

By the time I pried the last log from the frozen dirt, she had killed 14 rats, and the corpses littered the field. She turned her back and went to find my mother.

As Chuck aged she earned the sort of quiet deference afforded to elderly veterans. She would enter the packing shed during the interns’ morning meeting, and the other dogs would quit their begging and scraping for attention to make way, watching from the corners of their eyes until she chose which lap she wanted to sit in, which treats she would accept. When the others clamored for a place on the back of the pickups, Chuck headed back to the house to nap until lunch.

Years earlier, Fritter, a golden retriever mix, and the patriarch of a long line of dogs at the farm, had spent three days and nights in a quiet spot under the summer kitchen, when my father took me aside and explained the cold facts of death. During the closing parts of this speech, a fight broke out among the other dogs over an old blueberry pie, and Fritter came trotting around the corner of the barn, eager to claim his piece. He lived for another four years.

Chuck wouldn’t be a miracle. At 12 years old she was nearly blind and had lost most of her teeth, and tremors shook her little body. She still went with my mother to pick broccoli, but she sat in the cab of the truck now and watched quietly. She would hop down and sniff around the cut stems, but her milky eyes would always turn toward my mother and then the house, eager to get back to the old laundry basket where she slept.

My mother was away visiting my sister in Pittsburgh on the snowy night that Chuck left the house for the last time. There was no real way to know if she had a plan when she headed down the hill toward the creek. But my mother knew what had happened. Chuck had made her way to the frozen banks, looked at the cold water flowing by, and then, in her final act of dignity and courage, she had thrown herself in. We never found her body.

My mother cried when she told me, and she shooed Okra away from Chuck’s empty laundry basket. She didn’t pick broccoli as often as she used to, and you couldn’t always tell when she was collecting eggs, because Chuck wasn’t sleeping there outside the door of the chicken house. But then she adopted two kittens that scratched and mewled, and, after accepting them as the barn cats they were, she fell in love again.

I live in San Francisco now, and people in this town love their dogs–hard. But the Chihuahua at Peet’s Coffee wears a pink tutu that she would never have chosen herself, and the huge Newfoundland drinks from a tiny bottle of water instead of a puddle. No rotten pies, no severed deer’s legs, no scavenging the compost heap for them. When someone tells these dogs to “drop it,” that’s exactly what they do.

I love all these dogs too, the ones bred for cuddling, or loafing, or being dressed up in sunglasses by a 3-year-old. But spare a thought sometime for Chuck and her rats. If your dog must dig, let her dig. If she’s eager to run in the long, empty loops that trace the mystical geometries of canine ecstasy, let her run. Let her swim out too far, and lose sight of her in the snowy woods. Let her follow her dog-shaped dreams. Because that’s what we do for our friends.

Adapted from A Farm Dies Once a Year by Arlo Crawford, out now from Henry Holt.