Located more than 1,000 miles southeast of Tahiti, the Gambier Islands are where snails go to die.

Six million years ago, lava shot up through cracks in the Earth’s crust and into the South Pacific Ocean to form this archipelago of 10 islands. Over the ensuing eons, animals and plants arrived on the wind and waves (and sometimes on each other) and transformed the islands into functioning ecosystems.

Getting to a remote volcanic island on your own requires certain traits (it’s no coincidence there are no native elephants in Tahiti) and a lot of luck. According to a flurry of recent archaeological studies, land snails were particularly lucky and/or well-suited to life in the Gambier Islands. Ancestral snails arrived on floating rafts of vegetation or other detritus and, over millions of years, diverged into different species. The most recent research, published in Biodiversity and Conservation, reports the discovery of nine new species of land snail, bringing the total number of known snails from these islands to 46.

But here’s the catch—all nine new species are extinct.

Overall, 43 of the 46 species are extinct. Deader than a dodo. Gone before they could even get names.

They may not be cute and cuddly, but snails and other mollusks are worth our attention because they have taken a disproportionate drubbing in recent history: Of the 811 worldwide extinctions recorded over the past 500 years by the IUCN Red List, 308 are mollusks. I’m not sure what our beef is with Turbo, but it’s clear that in this human-caused period of mass extinction dubbed the “Anthropocene,” escargot is high on the menu.

“We care about things like [the extinct] woolly mammoth, but who will speak for these snails?” asks George Roderick, an invertebrate biologist at UC–Berkeley.

Perhaps Ira Richling.

Richling, a malacologist (snail scientist) at the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History in Germany, is the coroner for the Gambier Island snails. Her specialty is snails in the family Helicinidae, an overlooked group of 500-plus species found throughout the New World tropics, Pacific Islands, and Australasia.* Helicinid snails are so striking in their shape and color that they are actively traded in the conchology collector’s market. (I asked Richling if she knew any good snail jokes; her answer: “ .”)

Another snail expert, Philippe Bouchet of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, indicated that he had a trove of shells collected from the Gambier Islands, and oh, would Richling like to take a peek?

I asked Bouchet over email what initially led him to the desolate volcanic speck that is Mangareva, the main island in the Gambiers.

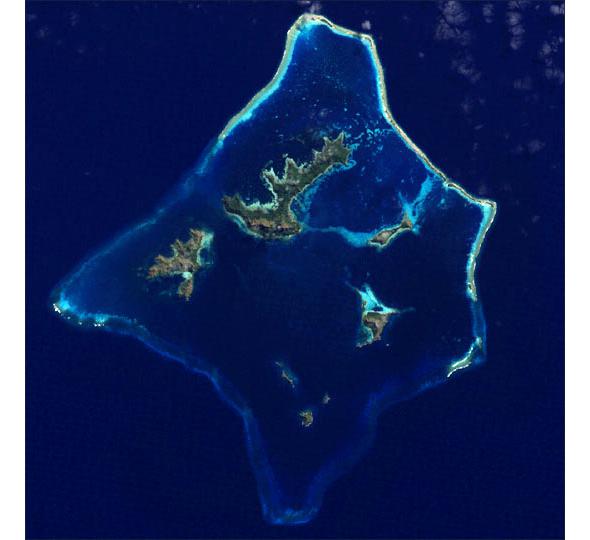

Gambier Islands from space.

Courtesy NASA/Wikimedia Commons

His response (caveat lector: my translation): “I wanted to benefit from the experience of visiting an island emblematic of the isolation and endemism of French Polynesia. I chose Mangareva, in the footsteps of [early 20th century malacologist] Montague Cooke. I went there for 10 days, all alone, and it was an unforgettable experience and a reminder of the transience of human societies and the vulnerability of oceanic islands.”

If only more of us wrote like that in emails.

It turns out Bouchet can get a lot done in 10 days. He brought back 50,000 shells in 1997 that Richling later examined, adding to the 861 he already had from Cooke’s 1934 expedition, the last comprehensive survey of snails done in the Gambiers.

Combing through the specimens, Richling found shells that were unlike any she had seen before. The snails were already long dead when Bouchet collected them, perhaps for up to 100 years, preserved in the island’s upper layers of soil and leaf litter. But the lack of live specimens in both the 1934 and 1997 expeditions suggests these species are no longer with us, Richling wrote. In fact, only one type of helicinid snail, Sturanya makaroaensis, is thought to be still alive.

The nine new species Richling and Bouchet plucked from the island rubble were so different from other snails that they created a new genus for them: Nesiocina, from the Greek nesios (“island”). Aside from their novelty, there were some other peculiar things about these snails—for one, they were unusually small. Many animals on islands are known for evolving into dwarf versions of their mainland counterparts, from pygmy mammoths on California’s Channel Islands to “hobbits” on the Indonesian island of Flores.

Could evolution have shrunk the snails? “Possible,” says Richling. “We don’t know enough.”

Another quirk was that several of the species had little knobs and protuberances around the openings in their shells, a trait seen nowhere else in Pacific Island helicinds. It’s possible these bumps provided some protection against predatory insects trying to get to the meat inside, says Richling.

A final mystery is how so many species could be found in the same place, considering the ecological principle that closely related species should compete with one another for food and other resources and thus have a hard time sharing the same niche.

We may never get answers to these questions, but perhaps we can get a handle on why they remain unanswerable—what drove these 43 snail species to extinction in the first place?

Snails are clearly not built for getting around—entire species are often restricted to limited areas, so if that landscape is modified or destroyed, so too go the snails. We know little about the natural history of these species, but we do know that their habitat got trashed by multiple waves of human invaders—first Polynesians, arriving somewhere around 900 to 1000 A.D., and then Europeans, who landed on the islands in 1797.

While both groups of colonists dramatically altered the natural landscape, clearing forest, planting crops, and introducing animals like pigs and dogs, it appears the snails withstood the initial Polynesian onslaught. Scattered museum records report snail sightings in the 1840s to1860s, and the recovery of so many extinct species’ shells in 1934 and 1997 suggests their demise was fairly recent. Our best guess is the snails took a beating when the Polynesians started destroying their habitat, and the Europeans finished the job with the addition of their technology, agricultural practices, and introduction of foreign species.

The Gambiers of today bear little resemblance to the environment in which these 46 snail species evolved. In postcards of the island, still an arrestingly picturesque place, almost all of the vegetation you see is not native, replacing species driven out by humans and their activities. The floral change was so dramatic that upon arriving at the island in 1935, botanist Harold St. John said the islands’ “natural flora is more completely exterminated than that of any other part of the world that I have seen.”

The second highest point on the island of Mangareva, Mt. Mokoto. Almost all the vegetation in this photo is not native to the island, representing the dramatic transformation wrought by humans.

Photo courtesy David Hembry

Extinction in the Gambiers is not confined to snails, unfortunately. Four land bird species and two plants found nowhere else are also gone. Untold numbers of insects, often the most diverse organisms in an ecosystem, are likely extinct as well.

Recent insect extinctions are hard to identify because their soft bodies do not preserve well. Yet David Hembry, a postdoctoral researcher at Kyoto University in Japan, used a work-around to detect a probable extinction, reported in the journal Pacific Science. He found leaf mines, burrowing trails left by a specialist moth, on the leaves of its host plant in old herbarium specimens, but he did not find the mines on the 10 plant specimens he found today. Nor did he see any of the moths. Although it’s impossible to prove a negative, the Magic 8 Ball of extinction says “all signs point to yes.”

In Richling’s words, it’s “already too late for the land snails” of the Gambier Islands. Islands are much more fragile than continents. As such, they are also a harbinger of what may come if we don’t decelerate our pace of modifying pristine landscapes and poorly managing already altered ones.

But it’s not too late for the thousands of other snails still out there, many of them yet unnamed, undiscovered, and unprotected. Focusing our energy on finding and documenting these species and understanding their role in their ecosystems, developed over millions of years of evolution, will mean we’ve learned from the Gambier gamble, which clearly did not pay off.

Finally, a malacology joke: A man goes to a Halloween party with a woman on his back. The host asks him, “and what are you?” The man says, “I’m a snail.” The host says, “and who’s that on your back?” And the man says, “That’s Michelle!”

Correction, Jan. 14, 2014: This post previously misidentified Ira Richling as a man.