Canadian outdoorsman Marco Lavoie spent three months stranded in the wilderness of the Nottaway River in Western Quebec. His plight began when a bear attacked and wrecked his boat, ravaging his supplies. Lavoie’s pet German shepherd apparently helped drive off the bear. Eventually Lavoie, starving and dehydrated, struck his dog on the head with a rock and ate him.

Lavoie’s actions earned him a torrent of criticism when he was finally found, 90 pounds thinner and dogless, earlier this month. While survival experts supported his decision, Lavoie told authorities immediately after the rescue that he wanted another dog, and this wish provoked particular ire. On the Huffington Post, for example, one commenter wrote “I would rather eat my own limbs than my dogs.”

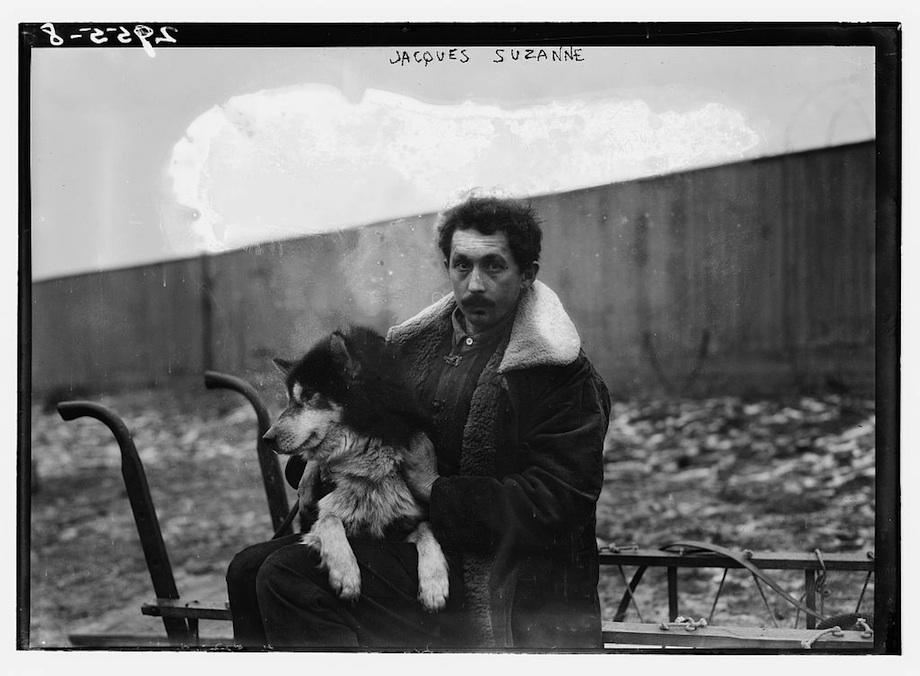

I wrote a master’s thesis on dog-in-the-wilderness stories, so the Lavoie tale, and the outraged public reaction, piqued my interest. Of the “Man and Dog vs. the Wild” genre, popular at the turn of the 20th century, we mostly remember the works of Jack London, a writer so loved that a new biography merits a long review in the New Yorker. Parents may be familiar with the real-life tale of Balto the sled dog, who brought diphtheria medicine to snowbound Nome, Alaska in 1925 and has been memorialized in children’s books, animated movies, and a statue in Central Park.

But many of the “Man and Dog” stories from the 1900s to 1930s now reside on the lower layers of the cultural landfill. Ever heard of Arthur Bartlett’s Spunk: Leader of the Dog Team (1926)? Ernest Harold Baynes’ Polaris: The Story of an Eskimo Dog (1924)? Esther Birdsall Darling’s Baldy of Nome (1916)? Probably not. Even John Muir’s story “Stickeen,” about a dog who traversed a dangerous Alaskan glacier at the explorer’s side, is now relatively unfamiliar.

What all of these stories have in common is a careful balancing of ideals of wildness and domesticity. Historian Gail Bederman, whose book Manliness and Civilization shaped a lot of my ideas, describes key conflicts within turn-of-the-century ideas of white masculinity. At a time of urbanization and modernization, Bederman argues, people were obsessed by wildness and tameness. Fears of the bad effects of soft city living were joined by equal fears of descent into total “savagery.” (This was a time when eugenics and cultural chauvinism were quite mainstream.)

Summer camps, wilderness recreation, and cultural tourism on Southwestern reservations, all of which were newly popular, were inoculations against softness. What all of these activities had in common was the promise that participation might give you just enough of that taste of wildness to get you through your everyday “civilized” life.

The dog in the wilderness was a perfect literary metaphor for the times. Dogs like London’s Buck in The Call of the Wild found their wild interior when they were forced up against the harsh realities of Alaskan travel. Dogs learned to fight, to eat wild game, and to persevere on long runs.

But through all of this exertion, they always loved their masters. Their wildness was never so complete as to foreclose that affection—and, indeed, many of the fights they engaged in were on behalf of those masters. Like Lavoie’s dog, they stepped between the dangers of the great North and their masters’ hides, turning “red in tooth and claw,” but for a purpose. The dogs in these stories, like the men they accompanied into the wilderness, were brawny, with a solid core of morality.

In using dogs as transportation, white explorers, missionaries, and prospectors were adopting a practice of the native Alaskan, but they staunchly held that they were doing it better. Hudson Stuck, a missionary who wrote a memoir called Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled, argued that native Alaskans had never figured out how to run dogs in teams, and it took white immigrants to perfect the concept. (Musher Scotty Allan and game warden Frank Dufresne agreed, taking credit for the invention of the harnesses and sleds that made rapid dog transportation possible.)

Sourdoughs in any number of stories contrasted white kindness to animals with native cruelty. At a time when the anti-animal cruelty movement gained traction nationwide, the stories embraced this particular emblem of “civilization” as one that differentiated white from native in the frozen North.

In a 1905 story by Addison Powell in Alaska Magazine, “The Alaska Partners,” a prospector’s dog, Summit, is kidnapped by native Alaskans, who have covetously observed his hunting prowess. Summit’s fate, “tied to a post with no food except an occasional raw salmon that a squaw threw to him,” shows the inferiority of native treatment. In Katherine Reed’s story “The Klondike Nugget,” published in Alaska Yukon Magazine in 1907, the heroic Prospector Dave’s very character is tied up in this difference. The narrator observes: “‘Go to Hell yourself but be white to your dogs’ was one of [Dave’s] favorite proverbs.”

Dog-eating, an extreme form of this kind of cruelty, was in these fictions a practice observed only by native Alaskans. In the 1933 film Eskimo, for example, Mala, the Inuit star, eats his dogs one by one when he’s lost on the ice. In a 1930 skit in which he played a sourdough, W.C. Fields made a joke at Balto’s expense, telling an inquirer that he “just et Balto,” and adding “Right good he was with mustard, too.” That joke worked because white prospectors were not supposed to eat their heroic companions, no matter how hard things got.

People angry at Marco Lavoie aren’t explicitly mad that he wasn’t “being white to his dogs.” But the long history of the “Man and Dog vs. the Wild” story can shed some light on the fury his action provoked. Taboos about the treatment of particular species, as Dana Goodyear explored in her recent story aboout eating and loving animals in the New Yorker, are wrapped up in a lot of cultural baggage. In the case of Marco Lavoie, we have years of stories telling us that we should starve rather than violate the man-dog bond.

That doesn’t mean the reactions to his case were uniform. Some of the most interesting responses to the Lavoie story can be found in the comments section of the conservative site The Blaze. Here, some commenters compared Lavoie to Obama, repeating the story that Obama ate dog meat in Indonesia while growing up. Other commenters shrugged, saying “Let’s just say he was resourceful.” One added: “If [Lavoie] would have died before eating his dog, his dog would have surly [sic] ate him.”