Without wanting to interrupt my colleague Emma Roller’s coverage—or interrupt the short time I’ve got to hammer out part of a book that has nothing to do with politics—I’d like to explain briefly how the Senate got here, and why Harry Reid confidently brought 51 of his 54 Democratics colleagues on board with a rules change that Washington long thought impossible: the end of filibusters on executive branch nominees and judicial nominees for lower courts.*

The Gang of 14 went extinct. You can start writing the history of the judicial wars at many points in time—the Bork nomination in 1987, the Republican filibusters of the Clinton years, the Democratic filibusters of the George W. Bush presidency. But the deal that kept a sort of peace for eight years was crafted in 2005, after a good election gave Republicans 55 Senate seats but Democrats kept blocking a posse of conservative nominees. Republicans threatened to rule filibusters out of order—this was quickly dubbed “the nuclear option,” and put lots of senators on the record with positions they would reverse when they switched majorities.

But it wasn’t ever clear that Republicans had 51 votes to push through the change. When seven Republicans joined seven Democrats to end the crisis, that seemed to confirm the cynics. The “Gang of 14” deal teamed up some of the Democrats’ elder statesmen, like Robert Byrd, with some of the more moderate Republicans.

Eight years later only five of the 14 Gang members remain in the Senate. Four of the Republicans were either defeated by Democrats or retired and replaced by Democrats (or, in Olympia Snowe’s case, an independent), all of whom backed filibuster reform. Three of the Democrats were replaced by more progressive senators, all of whom backed reform. Nebraska Sen. Ben Nelson was replaced by Republican Sen. Deb Fischer, who hasn’t found much of a leadership role in the Senate; West Virginia’s iconic Sen. Robert Byrd was replaced by dealmaking Sen. Joe Manchin, who would vote against a rules change but did not rally his colleagues against it.

Democrats stopped seeing the benefit of the old rules. Older, more patronizing members of the Senate liked to chastise the supporters of the nuclear option by pointing out that they’d never been in the minority. And that was true—Oregon’s Jeff Merkley, the soft-spoken ringleader of the reformers, had only arrived in the Senate in 2009, when the Democrats’ biggest problem was rounding up the pesky 60th vote for nominees. But Democrats new and old grew to mistrust the GOP.

“I know that if there is a Republican president and a Republican majority, they will force up-and-down votes because they demonstrated their committment to that principle in 2005,” Merkley told me this month. “There is, in a democracy, power that goes with the voice of the people.”

Merkley was both wide-eyed—hey, shouldn’t the winner of an election get up-or-down votes anyway?—and cynical. Over time, the party’s leaders and statesmen grew to agree with the cynical part. What had they gotten for the 2005 deal? A bunch of Republican judges and a promise that only “extraordinary circumstances” would stop future nominations. They felt that Republicans had broken the second part of the promise but would invoke it if they won the next election. By last week, when Judiciary Committee Chairman Pat Leahy was banging a dais about the “broken word,” it was clear that most Democrats agreed with Merkley. Did they want to put up with GOP filibusters for three or seven or 11 more years, then watch the barrier fall as soon as a new Republican president demanded it?

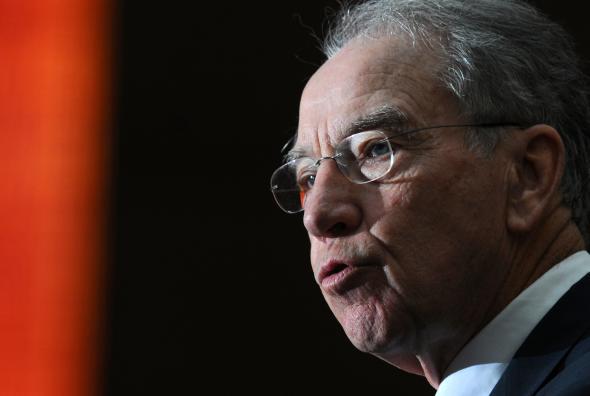

Chuck Grassley played chicken and lost. In June, when the White House announced three nominees for open D.C. Circuit seats, the Iowa senator started on a crusade to block them. He proposed redistributing two of the seats to other circuits, and nixing the third to save money. This, and not any ideological questions about the nominees, was the reason most Republicans filibustered them.

And that tore it. Democrats had no interest in cutting a deal; no Republican was emerging to craft one. In one year, even in the best circumstances, they were likely to lose a few Senate seats and fall below the majority needed for a rule change. Grassley, who’d arrived in the Senate in 1981, was emblematic of the new Senate GOP. He’d never voted against a Supreme Court nominee until Barack Obama was president. In the future, causes like his would be backed up by an increasingly right-wing GOP Senate caucus, as more Kay Bailey Hutchisons were replaced by Ted Cruzes and Bob Bennetts were replaced by Mike Lees.

There looked to be no stopping Grassley. So they revved up the deathproof car and ran right over him.

*Reid’s rule technically leaves Supreme Court nominees open to filibusters, but no nominee for that court has been filibustered since the introduction of the 60-vote threshold. Bork was defeated by an up-or-down vote; Clarence Thomas got only 52 votes, but Democrats, who ran the Senate, did not filibuster him.