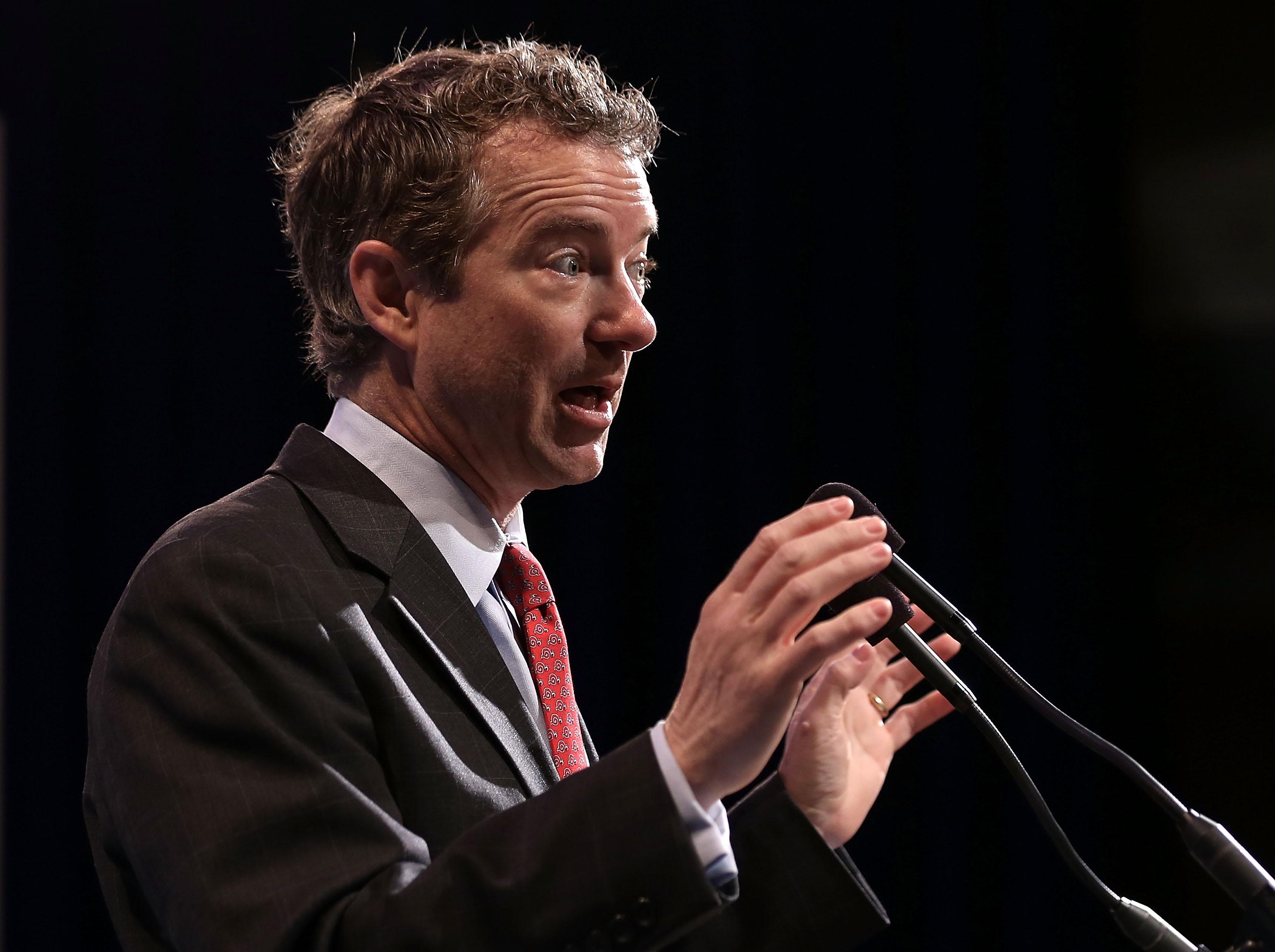

Rand Paul’s Wednesday speech at Howard University began shortly after 11 a.m. The speech ended around 11:27; the Q&A ended at noon. And yet the first pundit take on the speech was published at 11:18 by Washington Post opinion blogger Jennifer Rubin. She wasn’t thrown by all of the prepared text, but she knew it was working well for Paul.

It was a nervy effort on his part, and a sincere one, I think, to explain his views to an audience not enamored of his party or philosophy. He should do more of it, and in more concrete terms, to persuade and explain how his philosophy works and why liberalism doesn’t.

Today, National Journal’s Josh Kraushaar writes about the speech without as many caveats as Rubin.

He received a lukewarm reception at best, with his speech interrupted by protesters and hostile questioning. Already the takeaway from some news outlets is that Paul reiterated support for the 1964 Civil Rights Act, illustrating how politically risky such diplomacy entails. But the speech itself is a necessary test for the latest Republican proposition: that the first, necessary step to win over minorities is not just through policy proposals, but merely by showing up to make a case.

The connectivity: Neither writer was at the speech. In the room, Paul got a cool reception as he talked about Republican Party history. It wasn’t just that a dude with a sign decrying “white supremacy” interrupted him. The protester got up when Paul said “the Republican Party has always been the party of civil rights and voting rights.” The most vexing question was about the GOP’s active legislation demanding voter ID; Paul just said it was a calumny to compare that to “Jim Crow.” Paul’s best moments, and only applause, came when he shared his policy stances on drug laws and the death penalty.

But he wasn’t just talking to those students. The very existence of this Howard speech was supposed to impress white conservatives and black voters who would never see it. And the early indication is that this worked.