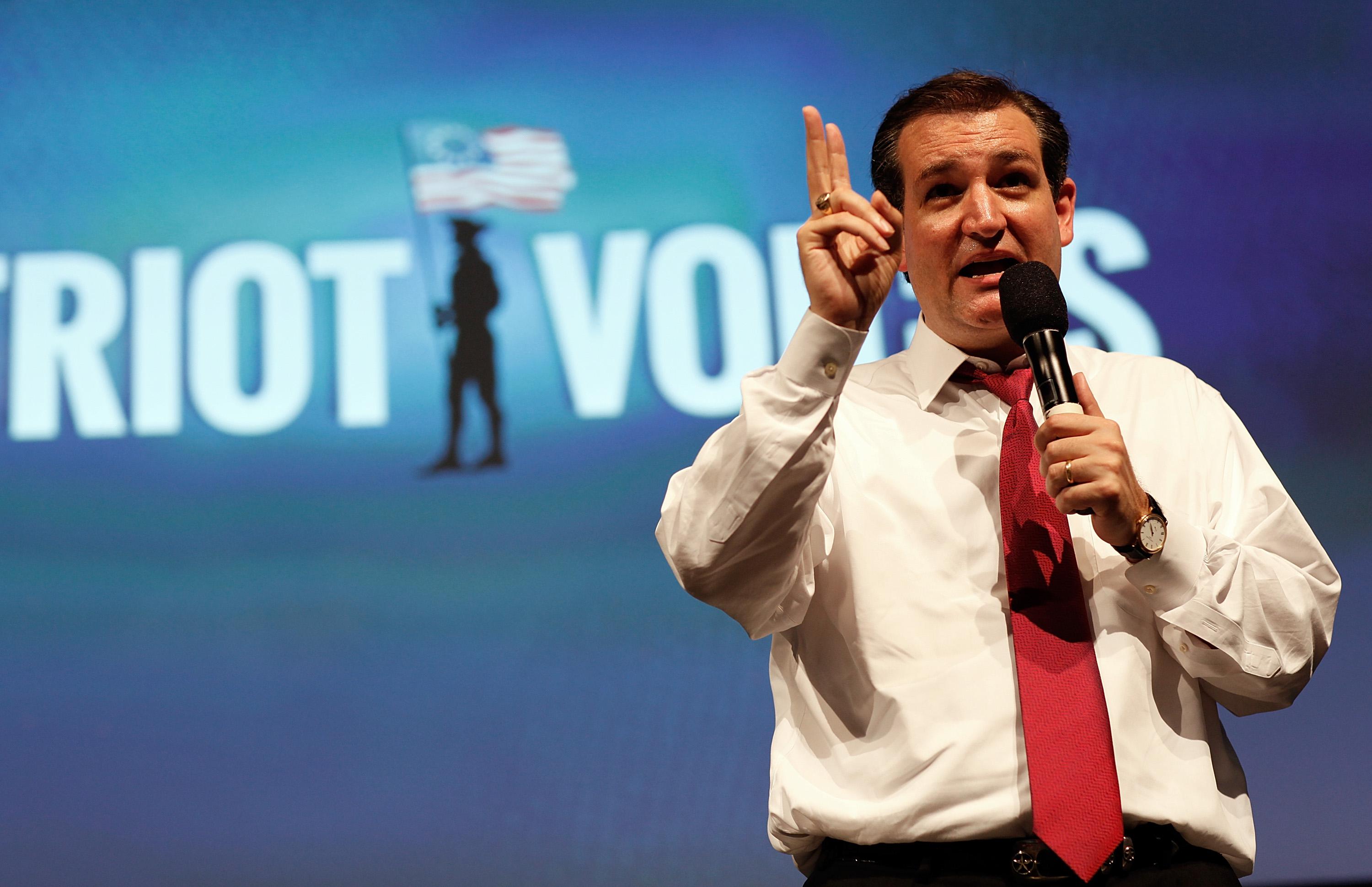

For a new story, I went back through the transcripts of Ted Cruz’s Supreme Court battles. For most of the aughts, Cruz was Texas’s chief lawyer, and his wins in that job formed the narrative of his Senate campaign. Cruz reminded crowds that he “fought the U.N. and won” by getting SCOTUS to agree that the Geneva Convention didn’t apply to foreign nationals wanting to wriggle out of death sentences. My basic finding: The manichean, listen-to-the-founders approach that does Cruz such good in the political arena often failed in court.

Frew v. Hawkins, for example, was a disaster for Cruz. The state had given him a weak case: It was arguing that federal requirements for improving health care didn’t apply to Texas, because of state sovereignty guaranteed by the 11th Amendment. Cruz’s own arguments foreshadowed some of the theories that would become conservative gospel in the Obama years. In 2004, they were met with a wall of laughter.

“I will point out if signing a consent decree is a waiver of 11th Amendment immunity or sovereign immunity, then plaintiffs’ argument proves too much,” said Cruz. “It means every consent decree is utterly immune from Ex Parte Young. It means once a consent decree is there, the requirements of Federal law don’t matter.”

“Only with the state attorney general,” joked Antonin Scalia.

Keep on reading. Cruz is undeniably smart and a first-class rhetorician, but there’s a lesson here about what works in political coverage and what works when the people making decisions are clued in to the precedents. Doesn’t speak particularly well of the media.