Ryan Lizza’s lengthly profile of Eric Cantor-in-power is worth reading. Even if you covered or watched the events recounted in the piece, you learn new factoids about what happened in the backrooms. And those factoids really firm up the popular image of Cantor. Lizza tracks Cantor’s movements during the pivotal moment of the “grand bargain,” the decisions that collapsed an ill-built deal.

Until late June, Boehner had managed to keep these talks secret from Cantor. On July 21st, Boehner paused in his discussions with Obama to talk to Cantor and outline the proposed deal. As Obama waited by the phone for a response from the Speaker, Cantor struck. Cantor told me that it was a “fair assessment” that he talked Boehner out of accepting Obama’s deal. He said he told Boehner that it would be better, instead, to take the issues of taxes and spending to the voters and “have it out” with the Democrats in the election. Why give Obama an enormous political victory, and potentially help him win reëlection, when they might be able to negotiate a more favorable deal with a new Republican President? Boehner told Obama there was no deal.

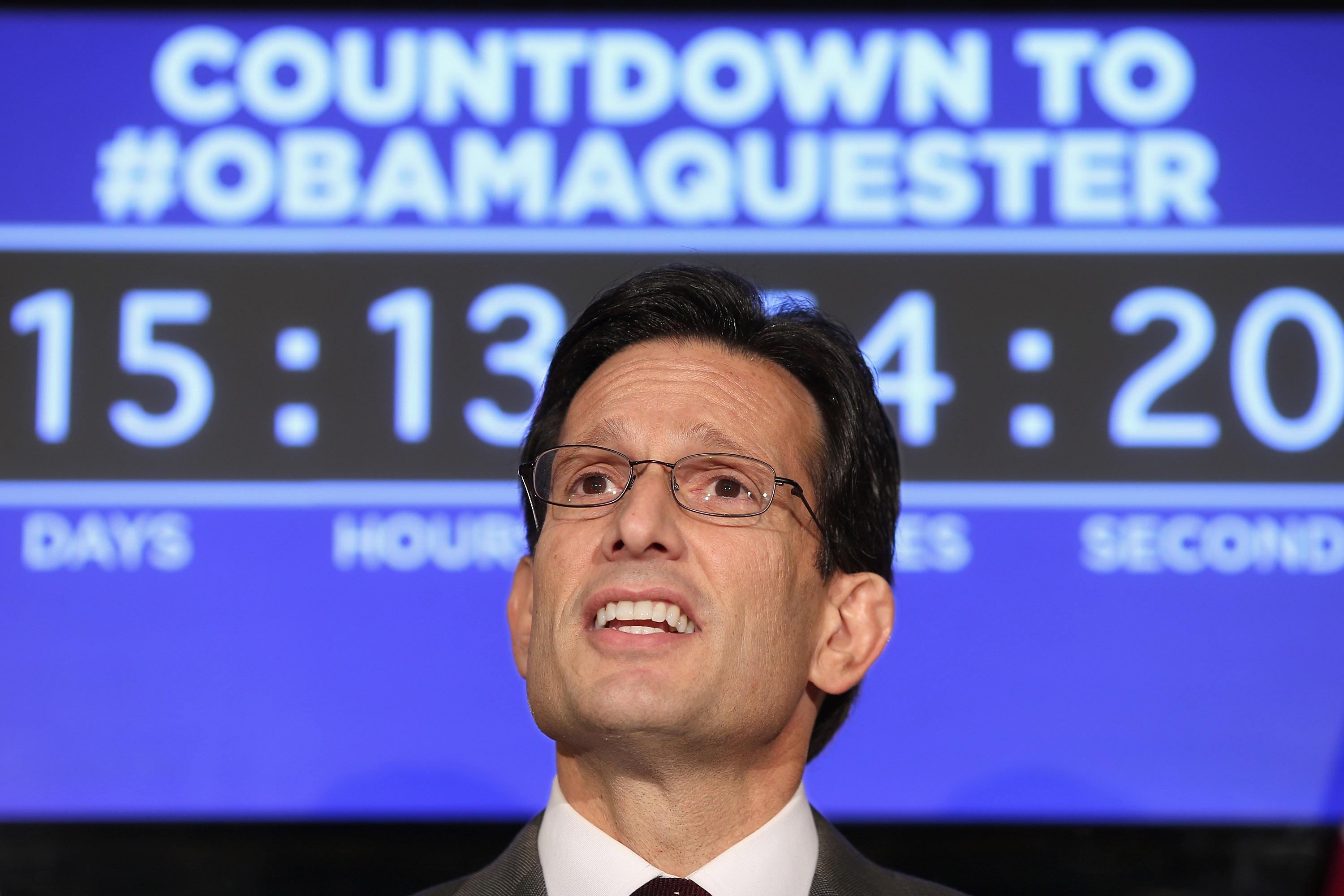

As Lizza writes, as you remember, the bet backfired spectacularly on Cantor, and Barack Obama was re-elected with increased Democratic numbers in Congress by portraying Republicans as the people who’d cut your Medicare to spare Donald Trump from higher taxes. Bad bet. What’s incredible is that Cantor went on to make the exact same calculation about the sequestration. I got into this at the House GOP’s retreat, where they decided to punt on the debt limit in order to schedule a better battle, on their turf, for late February. Lizza again:

Cantor viewed the various fiscal deadlines as what his aides referred to as hot stoves. “One is particularly hot,” Steve Stombres, Cantor’s chief of staff, said. “You touch the debt limit and you go into default, and that could be irreparable damage to our economy. But we felt like we could handle the heat of the sequester. We just needed to get them sequenced correctly and use that as an opportunity. The sequester was in place, and the members don’t want to give up that money, those cuts.”

That was five short weeks ago. Now, of course, Republicans are putting all their chips on a confusing argument about sequestration being both 1) the president’s horrible idea, and 2) not as bad as the president’s saying, when you actually stop and look at the cuts. They still aren’t in a good position to win the argument! I don’t think this is Cantor’s fault, really. The idea that you can be a deficit hawk while ruling out any tax increase, ever, is politically and mathematically untenable.