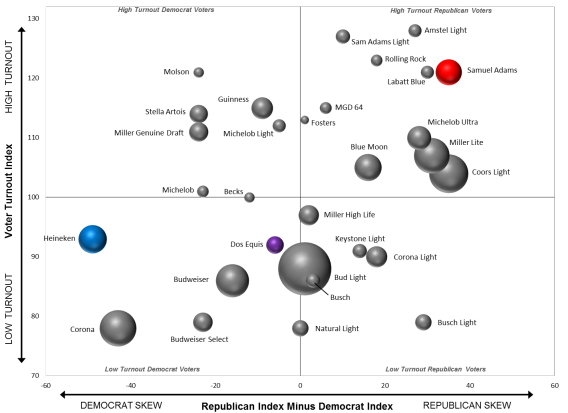

Yesterday’s most trafficked piece of political data candy was the above chart of beer brands arrayed according to the political orientation of their drinkers, which ran on National Journal’s website. Former George W. Bush ad strategists Will Feltus and Mike Shannon have become specialists in these displays, which are all based on voluminous studies that Scarborough Research conducts primarily to help advertisers distinguish the consumer habits of viewers of different television shows.

As 2004 approached, Feltus recognized that the Scarborough survey included two questions usually overlooked by commercial marketers, asking respondents about their partisanship and frequency of voting. It quickly became possible to plot TV audiences along those two axes, which Feltus used as a guide to which shows would be the best fit for reaching the Bush campaign’s targets. But the Scarborough surveys offered an unending trove of future insights: one could similarly map any other consumer preference that the firm asks its 200,000 respondents onto political orientation.

These nuggets contributed to one of the persistent mythologies that emerged from the Bush re-election campaign: that Republicans had won because Karl Rove discovered that his base drank Coors and bourbon. It was a notion floated in post-election interviews by some of the consultants who were looking to market this new “microtargeting” to other political clients, and argued extensively in the 2006 book Applebee’s America, by Bush adviser Matthew Dowd, who is a partner of Shannon’s in the firm Vianovo, and Ron Fournier, who now edits National Journal. (The third co-author was former Clinton aide Doug Sosnik.) The book ratified what might be considered the consumer fallacy of 21st-century of politics: that buying and lifestyle habits are the best predictor of political belief and behavior.

In fact, this has rarely been the case. The best predictors of political attitudes tend to be political attachments, and one doesn’t need to mine deeply into marketing research to find characteristics that separate Republicans and Democrats. The Republicans, for instance, tend to register to vote as Republicans, or in the places where that’s not possible—or it’s in greater vogue to call oneself an “independent”—vote in Republican primaries. The best predictor of one likelihood of voting is frequency in having done it before. Furthermore, even those consumer categories that might help to locate voters often don’t cover enough of the population to be terribly useful. After all, what share of voters have been identified as bourbon drinkers by a consumer-research firm?

Indeed, the consultants who had been involved in the Bush microtargeting project acknowledged to me for my book The Victory Lab that they entirely misrepresented the role that consumer variables like liquor preference or car ownership played in segmenting the electorate. “As we talked about this publicly we had to make stuff up,” Fred Wszolek, a Republican operative involved in the Bush microtargeting project, said. “We just wanted to keep them from knowing how accessible it is.”

Buried in the short National Journal essay that accompanied their beer chart, Feltus and Shannon effectively concede the point. They argue the data could offer insight into the consequences Dos Equis faces among consumers following the news that its “Most Interesting Man in the World” spokesman had hosted an Obama fundraiser. Because Dos Equis does not have a sharply defined partisan drinkership, Feltus and Shannon caution, the identification with Obama could prove perilous for the brand. “This is in contrast to its corporate sister Heineken, which as it turns out is the most Democratic beer of all,” they write. “On the other hand, Republicans love their Coors Light and favor Sam Adams, which is brewed just a few miles away from Romney campaign headquarters and whose namesake was an original tea partier.”

Indeed, Feltus and Shannon reach a conclusion that suggests there’s little value in any of these correlations for the political world.

We continue to advise big brands—who spend millions on consumer research—to make the investment to know where their fans stand politically and to put in safeguards to mitigate a political firestorm.

The implication is clear, and long overdue: political targeters shouldn’t waste time trying to translate insights from the beer aisle to the voting booth.