The Washington Post’s Phil Rucker today profiles the Madison Avenue team recruited by Mitt Romney’s campaign to produce his general-election ads. Rucker unfortunately lets his subjects get away with calling themselves “the Mad Men,” but gives them the chance to articulate their theories of a single ad’s power—arguably the greatest mystery to those who practice and study political communication.

Together, they clock 12-to-14-hour days in their shared offices and try to apply what they’ve learned in careers marketing Colgate toothpaste, Big Macs, BMWs and Nationwide Insurance to help pitch to the American masses a product that lacks a dominant market share: Mitt Romney.

…

Much of the money that Romney raises falls into the hands of the Mad Men, who already have cut spots and laid plans to blanket the airwaves in battleground states throughout the final 10-week sprint. Romney can raise all the millions there are to raise, but if his ad wizards don’t make compelling and persuasive ads, it won’t do him much good.

“We can keep throwing ads up there all day long, but is there an idea that’s really going to touch people? It’s going to get them to pull that handle, and we’re going to win,” said Jim “Fergie” Ferguson, the Texan.

The knock on Madison Avenue types dabbling in politics, from the 1950s onward, has been that they approach political campaigns as a form of consumer marketing. (“The idea that you can merchandise candidates for high office like breakfast cereal is the ultimate indignity to the democratic process,” Adlai Stevenson said in 1956.) But I find it hard to believe that Ferguson—whom Rucker credits with coining “It’s what’s for dinner”—considers the process of winning a vote for Romney the same as converting someone into a beef-eater.

These days, it seems that the corporate-advertising world has healthier and more intellectually honest conversations than political consultants about what a single ad can or cannot do for its products. Madison Avenue rarely operates under an election year’s accelerated timetable. They think in terms of cultivating consumers’ long-term attachments to brands, and seem comfortable with the notion that there is not always a direct relationship between an ad’s power and immediate market share. Political consultants can’t afford that patience, and always seem eager to claim short-term successes—attributing poll movement to a particularly memorable or distinctive ad, for example.

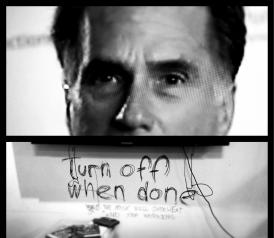

As a result, the conversation around political ads often ends up confusing aesthetics and effectiveness. The moment after I first saw the Obama campaign’s ad “Firms”—a thirty-second John Del Cecato masterpiece generally known as the Mitt-warbles-America-the-Beautiful ad—I tweeted that it was “an instant classic to remind [us] that, like abstract expressionism and bluegrass, attack ads are a great American art form.” It’s six weeks later, and while the distinctive ad appears to have helped sustain a media conversation about Romney’s personal finances, it’s unclear whether those thirty seconds had any direct impact on public opinion. Those who were asked to score it as part of an academic ad-rating project said it was “memorable.” There may have been an idea in there that touched people, but will it get any of them to pull that handle?