This past week was a good one for American interests in Iraq. A team of U.S. military advisers arrived on Mount Sinjar to discover that the combined gains made by American airstrikes and Kurdish forces had helped free thousands of Yazidis who had been stranded there without food and water. That discovery greatly reduced fears of a possible genocide and, the Pentagon said late Wednesday, along with it the need for a targeted rescue mission, which could have risked a direct, on-the-ground confrontation between U.S. soldiers and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. The following day, the foreign policy windfall continued when Iraq’s embattled prime minister, Nouri al-Maliki, announced that he’d drop his promised legal challenge and step down peacefully, an unexpected reversal that ended legitimate speculation of a devastating, destabilizing coup.

But one good week isn’t going to solve the puzzle that is Iraq, a country that continues to play an outsize role in American foreign policy a quarter-century after Operation Desert Storm. President Obama has made it clear that the current military intervention will continue, with additional airstrikes against ISIS and humanitarian airdrops to communities in need. Efforts to arm Kurdish and Iraqi fighters on the front lines against the Islamic State forces are likewise expected to continue. “Wherever we have capabilities and we can carry out effective missions like the one we carried out on Mount Sinjar without committing combat troops on the ground, we obviously feel a great urge to provide some humanitarian relief to the situation,” the president said Thursday afternoon while trumpeting the unexpected success at Sinjar.

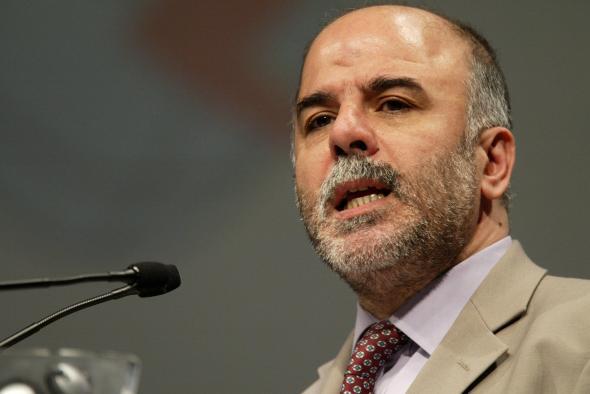

Exactly what happens next, however, remains unclear. U.S. officials had previously suggested that they would have more freedom to provide American aid—both military and humanitarian—if and when Maliki made way for a new government. But Obama’s made no secret of his belief that the long-term solution in Iraq isn’t just a new government, but a better government, one that is more inclusive and less sectarian than the one overseen by Maliki. That task now falls to Haider al-Abadi, a fellow member of Maliki’s Shiite Islamic Dawa Party and the former deputy speaker of parliament who has the next month to cobble together a coalition government.

The Sunnis and Kurds are expected to give Abadi the benefit of the doubt out of the gate, but it’s uncertain whether that is because of their confidence in him or just because they think that, by default, he can’t be worse than Maliki, who has been accused of stoking the sectarian conflict that experts say has greatly contributed to the current chaos in Iraq. Regardless, that good will could have a short shelf life depending on how Abadi goes about filling his Cabinet. Sunni and Kurdish leaders, experts say, will be looking for early olive branches, possibly in the form of positions running the powerful Iraqi ministries that control the military and police. Such appointments remain uncertain, however, especially given that, according to the New York Times, one of Maliki’s preconditions for stepping down was that members of his parliamentary coalition—which garnered a plurality of seats in April’s elections—“would be given their fair share of ministries and other positions.”

Still, the White House continues to express guarded optimism. “We are modestly hopeful that the Iraqi government situation is moving in the right direction,” Obama said Thursday. Of course, you don’t have to flip too far back in the history books for reasons for the president’s caution. It was less than a decade ago, after all, that Americans helped Maliki become prime minister, believing that he was the best man for the job (despite not knowing his real first name from his nom de guerre). Fears of history repeating itself exist inside Iraq as well. As one Iraqi put it when speaking to the Los Angeles Times: “Abadi is smarter than Maliki and he can learn from his mistakes. … But we liked Maliki in the beginning too.”

Adding to observers’ reservations is the fact that Abadi is a longtime member of the Islamic Dawa Party and a onetime Maliki spokesman. So while he is considered more secular and less likely to exclude Iraqi minorities from his government than the outgoing prime minister, Abadi doesn’t represent the cleanest of breaks from his former boss, whose pro-Shiite policies prompted Sunni and Kurdish resentment.

And, of course, there’s the not-so-small matter of the Islamic State fighters, the advances of which have been slowed but not stopped. As prime minister, Abadi is “going to face the same problem as Maliki; [ISIS] is not going to go away,” Hayder al-Khoei, an Iraq analyst at the British think tank Chatham House, told Foreign Policy. “It’s not rosy pink. The outlook is bleak, but there’s hope at least.”