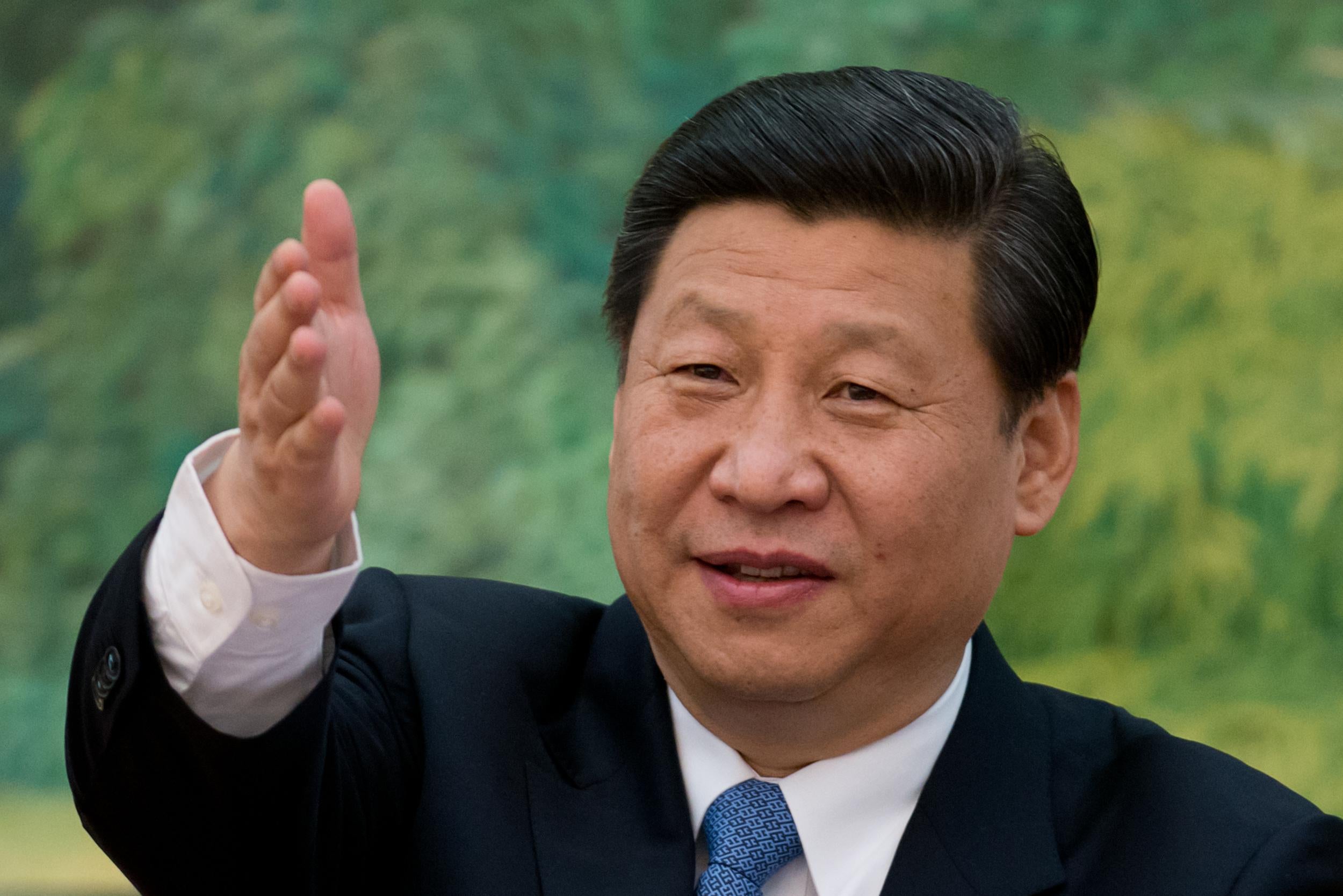

The New York Times’ Michael Forsythe reports that Chinese President Xi Jinping’s family members have been offloading assets as he launches an aggressive nationwide corruption crackdown:

From 2012 until this year, Mr. Xi’s sister Qi Qiaoqiao and brother-in-law Deng Jiagui sold investments in at least 10 companies, mostly focused on mining and real estate. In all, the companies the couple sold, liquidated or, in one case, transferred to a close business associate, are worth hundreds of millions of dollars, part of a fortune documented in a June 2012 report by Bloomberg News.

No investment stakes have been tied directly to Mr. Xi or his wife and daughter. But the extensive business activities of his sister and brother-in-law are part of a widespread pattern among relatives of the Politburo elite, who have built up considerable fortunes by trading on their family’s political standing.

The Communist Party disciplined 182,000 officials for corruption last year, a 13 percent increase from 2012. This has included heavy hitters like Zhou Yonkang, China’s retired former domestic security chief and until recently, the country’s most powerful oilman. More than 300 of Zhou’s relatives and associates have been taken into custody, and the former Politburo member is currently under house arrest.

Genuine concerns about corruption and the bad PR generated by the lavish lifestyles of senior Chinese officials may be motivating the crackdown—sales of Gucci bags and Ferraris have taken a dive in China since the campaign began—but it also seems to be a means of consolidating Xi’s power and sidelining potential opponents. Zhou, for instance, had reportedly angered Xi by opposing the ouster of controversial Chongqing politician Bo Xilai in 2012.

It seems likely that quite a few senior Chinese politicians have commercial interests that could be used against them or their families, and it makes sense that Xi would be taking steps to get his own house in order.

The 2012 Bloomberg report mentioned in the Times was also co-authored by Forsythe. Since then, he was suspended by Bloomberg following a dispute over the decision to spike another corruption-related story over fears that it would harm the company’s commercial interests in China.

The websites of Bloomberg and the New York Times are both still blocked in China, likely due to their reporting on the wealth of Chinese senior officials. But the government’s attempts to blackball critical journalists doesn’t seem to be stopping the unflattering stories from appearing in the international press.