Libya appears to be at risk of sliding back into civil war, with some of the worst violence seen since the overthrow of Muammar al-Qaddafi. Armed men loyal to retired Gen. Khalifa Haftar stormed the country’s parliament in Tripoli on Sunday, and intense fighting took place in Benghazi over the weekend. Haftar’s militia fought Islamist groups, including Ansar al-Sharia, which is blamed for the Sept. 11, 2012, attack on the U.S. consulate.

The current state of affairs is either the prelude to a military coup by Haftar or just infighting among rival militias, depending on how you look at it. It’s not the first near-coup the country has faced in recent months, and Haftar isn’t the only ex-military commander freelancing around the country with his own militia.

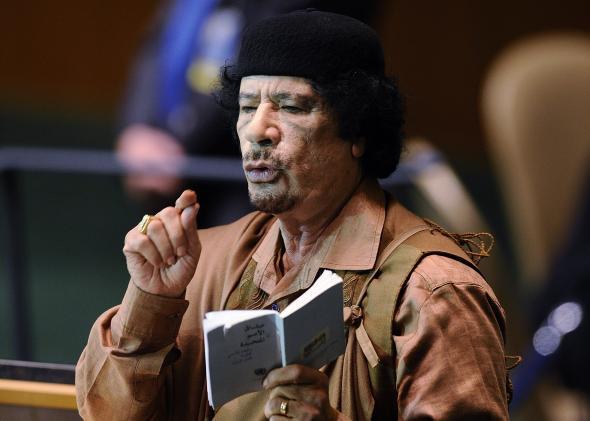

The precipitating cause of the current chaos is, of course, the internationally backed ouster of Qaddafi in 2011, but in many ways Qaddafi himself laid the groundwork for the deluge that came after him.

Unlike some of his dictator peers, Qaddafi never built up a strong military in Libya. As such, now that he’s gone, there isn’t a powerful central military force in the country. As the International Crisis Group’s Claudia Gazzini tells Al Jazeera, there’s a stark contrast between Libya and neighboring Egypt, where the military leadership structure has remained intact as it appears to be on the verge of installing a new strongman:

“Absolutely, some people might aspire to Egypt. …The problem is that in Libya you don’t have an Egyptian military. You have a very fragmented political and security scene, which is a recipe for continued fighting without conclusive results.”

As Robert Haddick of Small Wars Journal wrote in 2011, Qaddafi’s army was likely weak by design. The late leader was always more concerned about coups and internal uprisings than international threats. A strong military with a well-developed command structure could have created a situation in which—as with Hosni Mubarak in Egypt—the commanders pushed him aside in the face of popular discontent. For security, he relied instead on institutions like the Khamis Brigade, a special operations forces “Praetorian Guard” commanded by his son.

A 2010 analysis by the Center for Strategic and International Studies described the “militarily absurd” state of the country’s armed forces:

Libya has invested in equipment and facilities rather than a sound manpower, infrastructure, and support base. Its poorly trained conscripts and “volunteers” suffered a decisive defeat in Chad at the hands of lightly armed Chadian forces. Its forces have since declined in quality.

Libya’s military equipment purchases have been chaotic. During the Cold War and the period before Libya was placed under UN sanctions, its arms buys involved incredible waste and over-expenditure on equipment. They were made without regard to providing adequate manpower and support forces, and they did not reflect a clear concept of force development or combined arms. As bad as Libya’s military forces were, no neighbor could ignore the build-up of a vast pool of military equipment, although ties with its neighbors are warmer than in the past.

Libya has to keep many of its aircraft and over 1,000 of its tanks in storage. Its other army equipment purchases require far more manpower than its small active army and low quality reserves can provide. Its overall ratio of weapons to manpower is militarily absurd, and Libya has compounded its problems by buying a wide diversity of equipment types that make it all but impossible to create an effective training and support base.

What Qaddafi’s paranoia essentially created was a country with a disorganized and underdeveloped central military that was nonetheless flooded with heavy weaponry. In other words, once a power vacuum emerged, there was a perfect mix in place for violence and chaos.