Afghanistan suffered one of its worst natural disasters in more than a decade last Friday, when a massive landslide buried a third of the village of Abi Barak in the northeastern province of Badakhshan. A rescue effort is ongoing, but hope is dwindling for the more than 2,000 people buried by the mountain slope, which collapsed after days of heavy rainfall.

Given their relative frequency and geographical range, it strikes me that landslides—mass movements of soil or debris often caused by seismic activity or flooding—get relatively little attention compared with other natural disasters. Just last month, 36 people were killed by a landslide in Washington state. Countries ranging from China to India to Uganda have experienced catastrophic landslides in recent years.

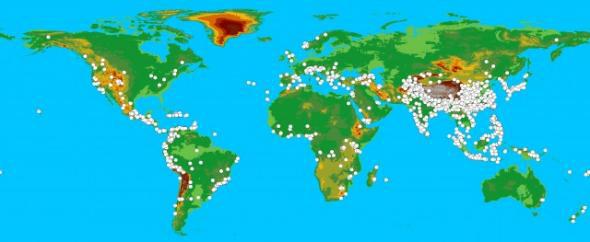

According to research by David Petley, a geographer at Durham University, the number of casualties caused by landslides has been massively underestimated. In a 2012 paper for the journal Geology, he calculated that between 2004 and 2010, there were 2,620 fatal landslides around the world, killing a total of 32,322 people. As Nature points out, that means landslides kill far more people than wildfire and about half as many as floods. These fatalities are mapped below to give an idea of the world’s landslide hot spots, which include Central America, the Andes, China, India, Indonesia, and Southeast Asia:

David Petley

The places most at risk for landslides are those that feature high relief—meaning large differences in elevation—high levels of rainfall, and high population density. Seismic activity is also a risk factor. Strong El Niño events also increase the likelihood of landslides in Central and South America.

Petley’s data seems to indicate that the number of landslides around the world is increasing, likely due to “increases in population, precipitation intensity, and environmental degradation.”

In the case of Abi Barak, photos show that the slope near the town was likely unstable for some time, which means that this disaster was likely a forseeable event that could have been avoided through management and monitoring.

“A landslide hazard identification and mapping programme in this highly landslide-prone area of Afghanistan would be far cheaper than the cost of this single landslide,” Petley writes on his blog. “Given that the expertise is readily available around the world to undertake this type of exercise, it is a folly that it is not being done.”

Abi Barak, of course, is located in one of the most remote regions of one of the world’s most unstable countries. But last month’s disaster in Washington may have been similarly forseeable. Given the environmental and population factors that seem to be making these events more common and more deadly, it may be time for the problem to receive some more attention.