The ongoing crisis in South Sudan is entering a critical phase, with the impending risk of both full-scale ethnic violence, or even genocide, combined with a likely famine. According to the United Nations this week, more than 9,000 child soldiers have been recruited in the conflict, which has displaced more than a million people.

But just days after hundreds of people were killed in an apparent sectarian massacre in the town of Bentiu, there does appear to be some progress on the diplomatic front.

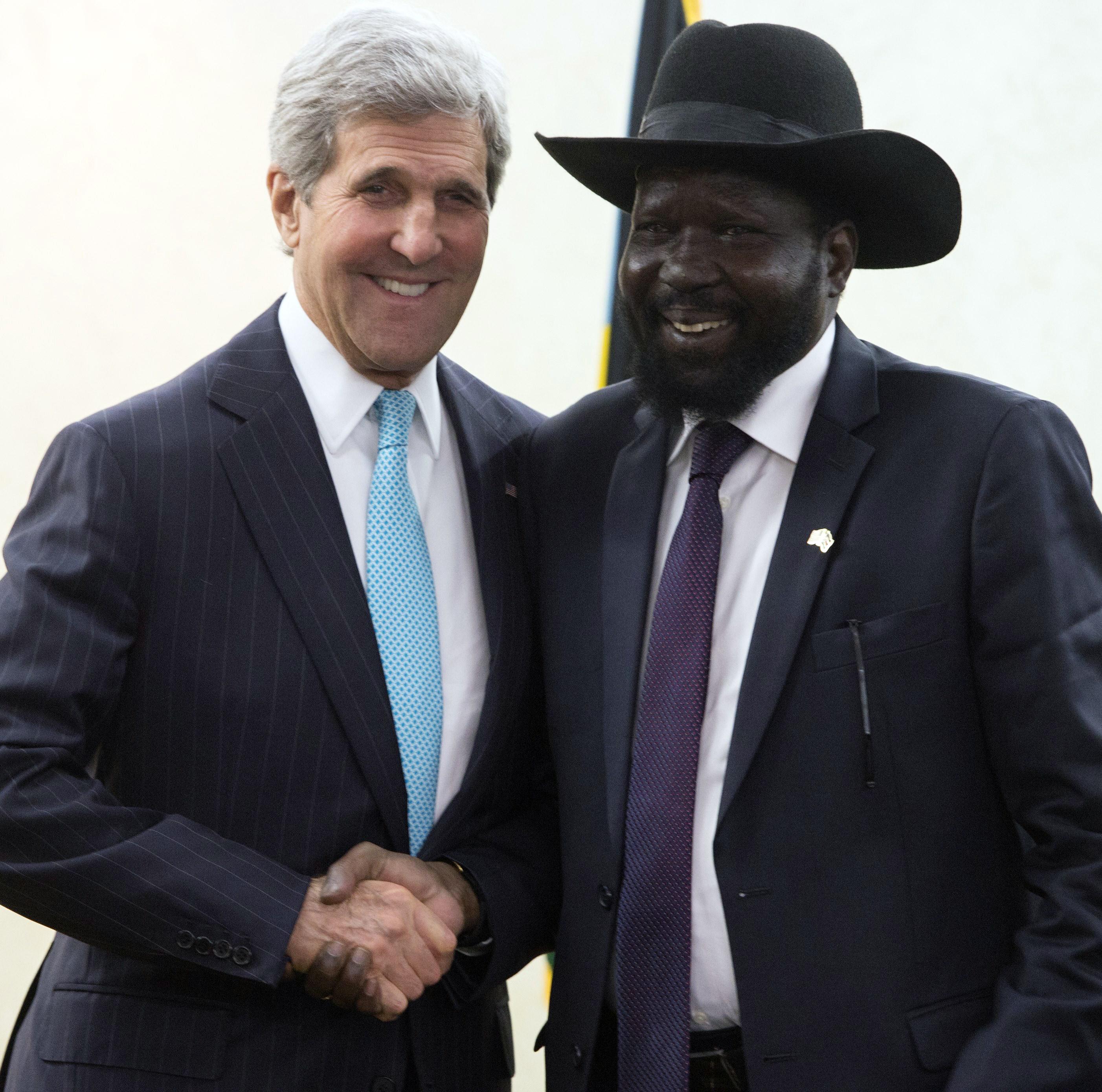

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, who is visiting the country today, announced that President Salva Kiir has agreed to restart peace talks with his former vice president, Riek Machar. The violence, which began in December, started as a political feud between the two men, and transformed into a much larger conflict between Kiir’s Dinka, and Machar’s Nuer ethnic groups. African Union troops may also soon be headed to the country to support a U.N.-led peacekeeping effort.

If the fighting does slow down soon, the reasons may be more environmental than political. South Sudan’s rainy season will begin in the next two months, which will make fighting difficult.

“It is possible to stop the violence, but stopping the violence does not stop the conflict. We’ve seen that multiple times,” David Abramowitz vice president of policy at the U.S.-based human rights NGO Humanity United, told Slate. “Come the fall and the early winter, when the dry season comes, the fighting starts back up.”

Abramowitz, who recently co-authored an open letter to Kerry calling for a more active U.S. approach to the crisis, suggested that the next few weeks could be particularly dangerous for civilians as the “sides try to position themselves before fighting grinds to a halt.”

As the planting season for farmers has already been disrupted in many parts of the country, Sudan Sudan faces an acute risk of food crisis in the coming months, which is likely to exacerbate the violence if it starts up again.

And even if a diplomatic accord is reached between Kiir and Machar, there’s also a question of just how much control these two have over events on the ground. “The Nuer community is not a monolithic ethnic group,” Abramowitz says. “There are subgroups and commanders who have their own interests. Not all of them look to Riek [Machar] for leadership. Some got in because they had their own relatives killed at the beginning of the conflict. Just because they’re affiliated with him, doesn’t mean he’s in control. ”

One example of such a group may be the much-feared White Army, a Nuer militia that’s been fighting on behalf of Machar but has been operating since the early 1990s is likely not not fully under his control.

“There is a risk of this conflict becoming even more complex, which would make it much harder to pull it back from the brink,” Abramowitz says, pointing to reports that Arab traders, not affiliated with either side, may have been killed in the Bentiu massacre, possibly in retaliation for reports that some Arab militants are fighting on behalf of the government.

In other words, it seems quite possible that we may be heading for a lull in the conflict—not likely not in the humanitarian crisis—but that violence could start up again in a few months. Abramowitz suggests that an actual resolution could require “some sort of transitional government which is made up of people who are mostly not in the current government.”

But Kiir, once a popular figure in the United States when South Sudan’s independence was a cause celebre in Washington, doesn’t seem like he’s in a hurry to take his black cowboy hat out of the ring any time soon.