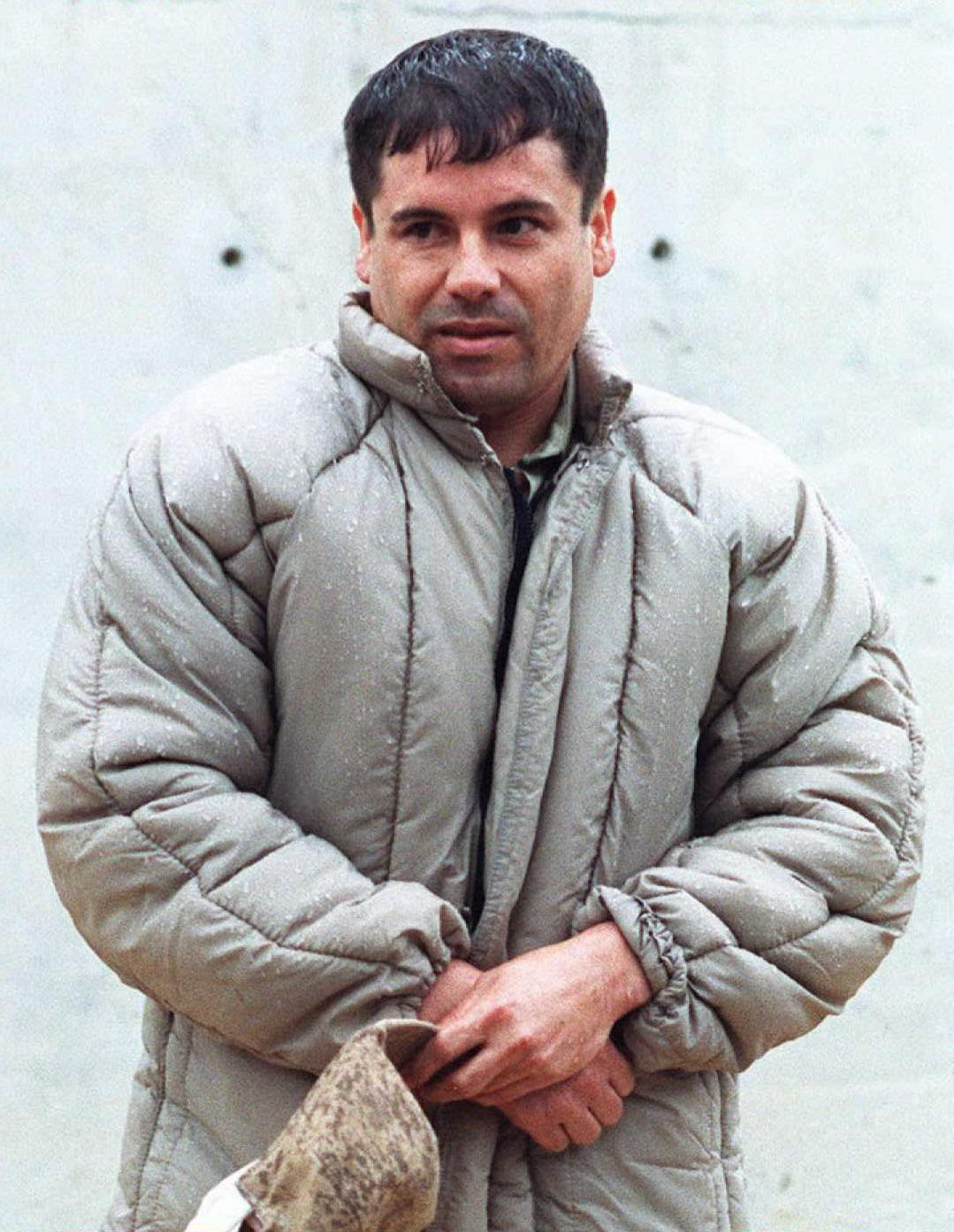

The arrest of the powerful and elusive Sinaloa Cartel boss Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán will, for at least a short time, be a major notch in the belt for the government of Enrique Peña Nieto, who promised to reduce Mexico’s drug violence after the carnage that took place under his predecessor, Felipe Calderón, during whose tenure nearly 60,000 Mexicans lost their lives in drug-related violence.

Nieto has promised to focus more attention on the economic causes of drug violence rather than just breaking the cartels, but he still likely relishes the sight of men like Guzmán—or Zetas boss Miguel Ángel Treviño Morales, who was arrested last summer—in handcuffs.

The government also points to the murder rate, which had begun to level off in 2012 and now appears to be declining. There are also visible improvements in places like Ciudad Juárez, the U.S. border city that was once ground zero for gang violence but is showing signs of improvement. Mexicans are now far less likely to report daily experiences with drug violence.

But the country is hardly out of the woods. According to the government’s statistics, the 18 percent drop in murders in 2013 was accompanied by a 35 percent increase in kidnapping. And Molly Molloy, a research librarian and a specialist on Latin America and the U.S.-Mexico border at the New Mexico State University Library, argues that the declining murder rate is the result of the country’s statistical agencies classifying fewer killings as “intentional homicides,” coupled with the fact that “the epicenters of extreme violence have dispersed around the country, making it more difficult to know how many people are dying.” She argues that there’s no evidence to suggest the total number of murders has declined at all, though different regions have seen changes in the level of violence.

With street prices of cocaine, heroin, and marijuana continuing to fall in the United States at the same time that the number of seizures is increasing, there also doesn’t seem to have been much of an impact on supply.

It also seems quite plausible that Guzmán’s capture could lead to an uptick in violence. The Sinaloas have reached an extraordinary level of dominance, largely edging out their rivals for control of the smuggling corridors of Tijuana and Juárez. They are thought to control most of the Pacific coast and central Mexico as well as having assets in every continent on Earth. According to a Bloomberg investigation last year, they supply “heroin, cocaine, marijuana and methamphetamine” in Chicago.

This dominance wasn’t easy to come by. In particular, the battle with the Zetas for control of Juárez may have cost 10,000 lives between 2010 and 2013. If Juárez is more peaceful today, it’s likely partially because the Sinaloas have fewer serious rivals to fight with.

But with Guzmán now out of the picture—assuming the authorities can actually hold on to him this time—one of the world’s most lucrative criminal empires may be vulnerable to competition again, not to mention the likelihood of intracartel violence as rival leaders seek to maintain control over supply routes. And keep in mind, the Sinaloas actually have a reputation for being less brutally violent than their rivals the Zetas, or Michoacán’s Knights Templar.

Guzmán may be the biggest arrest yet in the eight years of the drug war. But putting famous men in handcuffs every few months hasn’t had much success as a strategy so far.