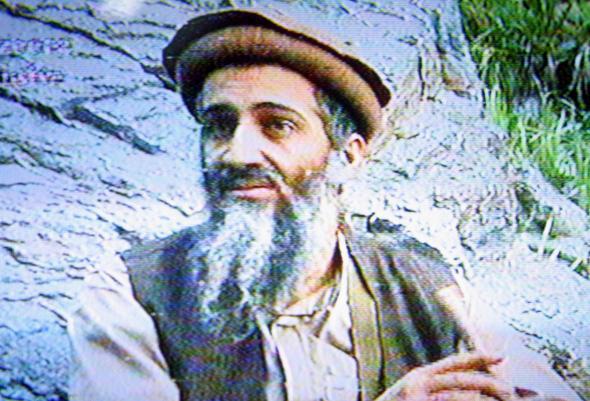

An interesting new study published in the journal Security Studies makes the argument that what made Osama Bin Laden an effective terrorist leader was not as much ruthlessness or charisma—though he possessed both—but an ability to spot good ideas from both his subordinates and from outsiders.

The history of terrorist innovation is one of borrowing, adapting, and refining as much as any other field. The IRA didn’t invent the car bomb but perfected its use in the 1970s. The Tamil Tigers borrowed suicide bombing as a tactic from Hezbollah, making it the brutal trademark of their decades-long war against the Sri Lankan government.

Assaf Moghadam, an authority on al-Qaida tactics at the Interdisciplinary Center in Herzliya, Israel, argues in the paper, and a shorter summary on the Lawfare blog, that studies of how terrorists innovate have focused too heavily on top-down ideas:

The few studies devoted to the analysis of terrorist innovation are almost unanimous in highlighting the central role played by a group’s leadership in the innovation process. Scholars cite the key role played by Shoko Asahara in pushing Aum Shinrikyo’s development of nerve gas in 1995 and point at Brazilian revolutionary Carlos Marighela’s central role in devising the strategy of diplomatic kidnapping. Wadie Haddad’s influence on the PFLP to adopt airline hijacking is considered to be critical, as is Menachem Begin’s pivotal role in formulating the glass-house strategy. Ahmed Jibril is accorded a central role in pushing development of a number of the PFLP-GC’s innovative tactics, such as using barometric pressure devices to blow up aircraft and deploying motorized hang-gliders to penetrate enemy territory

Studying the ideas that led to the 9/11 attacks, Moghadam argues that “[i]n stark contrast to other terrorist organizations, al Qaeda is known to be receptive to proposals for terrorist attacks from a variety of jihadi entrepreneurs. Being so inclined, al Qaeda internalized modern forms of business management such as a flat organizational structure and flexible strategy, applying them to a transnational terror organization.”

He quotes the terrorism analyst Bruce Hoffman, who likened Bin Laden to “a venture capitalist: soliciting ideas from below encouraging creative approaches and ‘out of the box’ thinking, and providing funding to those proposals the thinks promising.”

The archetypal example of this process was Bin Laden’s support for 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, a kind of terrorist entrepreneur who, for a time, refused to formally join al-Qaida and, reports suggest, “might have carried out the 9/11 attacks [even if they had been] supported by an organization other than al Qaeda, provided that the organization could have supplied him with money and manpower.”

Moghadem describes how KSM developed the idea for the attacks over time, learning in particular from the failures of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and the Bojinka Plot, a foiled plan to blow up a dozen U.S. airliners in Asia.

The study of how these groups build on each other’s mistakes and successes seems particularly pertinent given the relative decline in the reach and influence of al-Qaida-central—now led by Bin Laden’s successor Ayman al-Zawahiri—compared with its various offshoots.*

One other interesting factor that Moghadem identifies but doesn’t go into in depth is al Qaida’s “strange fascination with striking the international airline industry.” In the years since 9/11, the organization and its affiliates seem to have focused their most audacious plots on attacking airplanes, even as security surrounding planes and airports has gotten ever tighter compared with other potential targets. The obsession does seem a bit odd.

*Correction, Feb. 11, 2014: This post originally misspelled Ayman al-Zawahiri’s last name.