There’s an interesting parallel emerging in the arguments of those attacking NSA leaker Edward Snowden and those of the critics of the programs he exposed. For example, here’s Josh Barro writing in Business Insider on why Snowden “deserves a long prison sentence”:

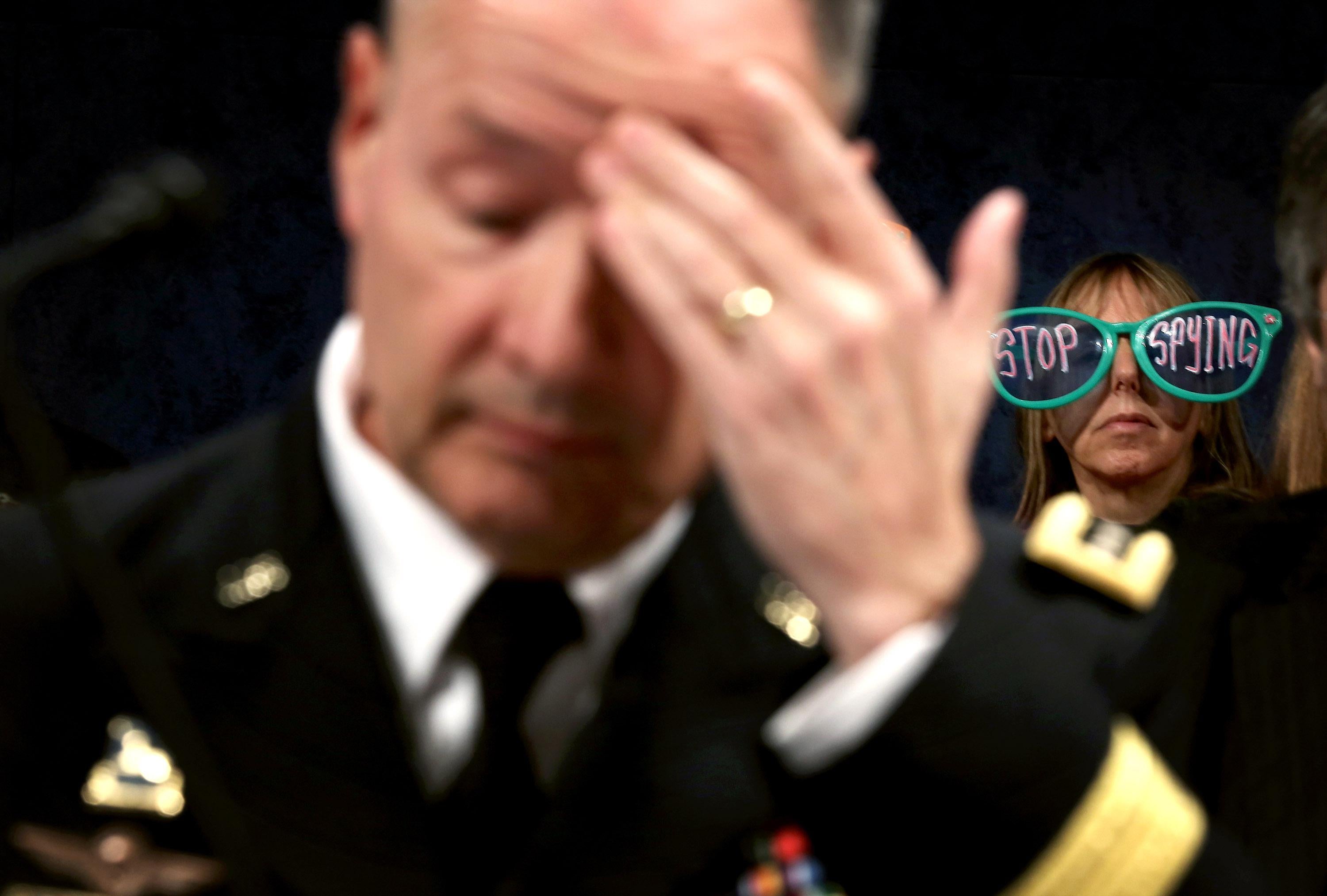

Snowden’s wide-ranging disclosures of secret documents did reveal some matters of genuine public interest, which should never have been secret, particularly the extent of the National Security Agency’s collection of electronic data on Americans. They also made clear that Director of National Intelligence James Clapper lied to Congress about what sort of data the NSA was collecting (tortured explanation from DNI General Counsel Robert Litt notwithstanding). This has had a positive effect on the public discourse, which I acknowledge.

But the key term in my description of Snowden’s leaks is “wide-ranging.” Snowden also disclosed a large number of documents that had nothing to do with Americans’ privacy. His disclosures include information about U.S. hacking of Chinese computer systems; U.S. spying on Russian President Dmitri Medvedev during the 2009 G20 summit London (and simultaneous British surveillance of other targets); the existence of 80 NSA listening stations around the globe, including one in Berlin which was used to monitor the cell phone of German Chancellor Angela Merkel; and much more.

Putting aside the issue of which foreign governments Snowden may have shared data with, which Fred Kaplan addresses here, the issue many have with his actions is less the leaks themselves than their scale and his seeming lack of discernment.

Some certainly feel that it would always be wrong for an NSA employee to leak government secrets. But there are others who believe that whistleblowing is necessary for the public good, and that violating professional or legal obligations in the process is sometimes justifiable, but also feel that the massive data dumps facilitated by people like Snowden and Chelsea Manning don’t distinguish between information the public needs to know and valuable intelligence-gathering functions.

On the other side, there may be those who believe that the U.S. government shouldn’t be gathering intelligence on foreign governments or potential security threats at all. But the more common position is that intelligence services need to spy sometimes, even on allies, but that the NSA bulk metadata collection on both U.S. and foreign citizens goes far beyond the agency’s mandate.

Obviously I’m simplifying both positions and there are other complicating factors on both sides, but the common thread here is that while gathering/publicizing certain information, even by ostensibly illegal means, about legitimate targets is justifiable under certain circumstances, doing it with terabytes of data goes too far, even if motivated by the best of intentions.

Yes, “Big Data” is an irritating cliché at this point, but in this debate it does really feel as if we haven’t fully grappled with the moral implications of the amount of data storage and processing power available to us. In 1970s a mass leak involved picking locks and packing documents into suitcases. Generally, you were forced by circumstances into being a bit more discerning about what you could send to the New York Times. Similarly, the FBI agents carrying out COINTELPRO could only dream of things like three-hop phone surveillance.

The same factors that made it easier for the NSA to collect so much data made it easier for Snowden to release so much. And they also seem to be making people who are normally comfortably on one side or another of the privacy/security debate very uneasy.