My colleague Dave Weigel passed along this pretty embarrassing 1985 column by George Will opposing U.S. sanctions on South Africa in which he argues that “the current campaigning against South Africa is a fad, a moral Hula Hoop, fun for a while.”

But take away the haughty dismissiveness and the racial fear-mongering about the carnage that would surely result if the apartheid regime were to fall, and his basic argument isn’t a particularly unusual one, and one frequently applied to other regimes, from Cuba to Iran to North Korea. He argues that sanctions will merely punish ordinary South Africans while strengthening the government:

Thanks to an oil embargo against South Africa, it is nearly self-sufficient, with the world’s best process for producing oil from coal. Thanks to an arms embargo, South Africa, which was 60 per cent dependent on imported arms 20 years ago today is 90 per cent self-sufficient and a net arms exporter.

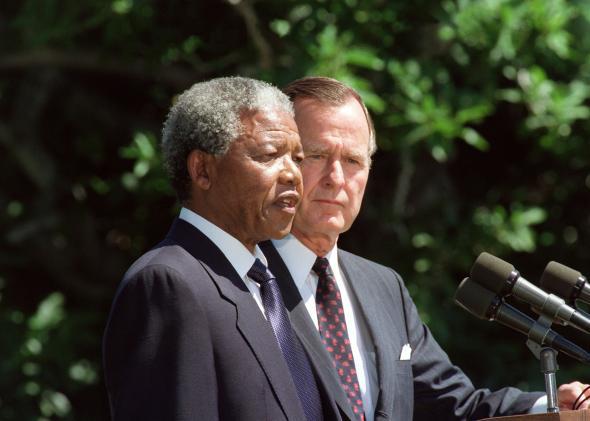

Today, the international sanctions against South Africa, along with the public divestment campaign in the United States and other countries, are remembered as the textbook examples of how international economic pressure can create the impetus for political change in repressive regimes. Of course, it would go too far, and give far too little credit to Nelson Mandela and his allies, to argue that international pressure was the main reason that apartheid fell. In the years since, some economists have even questioned just how much impact they really had.

In a 1999 paper, Phil Levy, then of Yale, argued that sanctions had far less of an impact on the situation than other factors including “the effectiveness of the political opposition of the black majority; the inefficiency and growing economic cost of the apartheid system; and the fall of the Soviet Union.”

A study by two University of California economists that same year looked at the widespread anti-apartheid divestment campaign, which movements ranging from opponents of Israel’s West Bank settlements to climate change activists have pointed to as a model, and found that “Despite the prominence and publicity of the boycott and the multitude of divesting companies, the financial markets’ valuations of targeted companies or even the South African financial markets themselves were not easily visibly affected.”

All the same, even if the economic impact of the sanctions and boycotts has been overstated, the psychological effect of them was clearly profound. As Levy acknowledges, “The sanctions signaled the extent to which South Africa was isolated in the international community.”

As one concerned high-level South African banker put it to the New York Times in 1988, ”In this day and age, there is no such thing as economic self-sufficiency, and we delude ourselves if we think we are different. … South Africa needs the world.”

This goes to support the argument that sanctions are most effective against governments that want to trade with the countries sanctioning them and are sensitive to international public opinion. A country like South Africa, which had been a close U.S. ally throughout the Cold War, was more sensitive to sanctions than a place like North Korea or Cuba.

The anti-apartheid movement was also effective because of the level of popular support it received. Former Free South Africa Movement Coordinator Cecelie Counts explained it well earlier this year to the New York Times:

The 1976 Soweto uprising was the catalyst for new energy and sustained mobilization and protest. Local coalitions, candlelight vigils, picket lines, organizational caucuses against apartheid multiplied drastically. Most campuses saw heightened activity after Soweto. College students took over buildings and walked out of class in solidarity with their South African counterparts.

The apartheid regime’s brutality reached a new level in 1984, and one response came when the Free South Africa Movement engaged people from all walks of life in daily demonstrations and in civil disobedience for more than a year. Shantytowns sprung up on college campuses that had not yet divested, an international campaign against Royal Dutch Shell was launched in 1986. The groundswell of opposition to apartheid led Congress to override President Reagan’s s veto of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.

Divestment began to affect South Africa as corporations let apartheid leaders know that it had become too expensive to continue operating there. Some would argue that many corporations simply shifted to indirect investments, but when banks began to refuse to renew loans it caused some real pain as the value of the rand fell.

The American public hasn’t been as enthusiastically involved in a human rights issue in another country since. In general, I wonder whether Western pressure campaigns that align with the goals of the majority of a country’s population—as they did in South Africa—may have more of a chance of success than movements such as the Free Tibet or Save Darfur campaigns, which aim to support the rights of particular regions or minority groups under pressure from larger majorities.

In any case, along with the usual litany of failures—Robert Mugabe, Omar al-Bashir, and the Castro brothers are still in power, Bashar al-Assad is looking more likely to prevail—recent years have also given powerful examples of when sanctions can be effective. They clearly played a role in pushing Iran to the nuclear negotiating table this year and played some role in Myanmar’s opening up.

In the 1980s, opponents of sanctions on South Africa including George Will and Ronald Reagan dismissed them as a feel-good tactic that would have little practical impact on South Africa’s apartheid laws. “If Congress imposes sanctions,” Reagan said in 1986 speech, ”it would destroy America’s flexibility, discard our diplomatic leverage, and deepen the [South African] crisis.”

That clearly wasn’t the case—whatever their economic impact but given the uniqueness of the situation, it’s a bit hard to draw wide-reaching lessons from their success. It’s unfortunately also hard to imagine another international human rights issue that the U.S. public would embrace to such an extent for so long.