The release of the 2012 scores from the Program of International Student Assessment, an exam given every three years that tests students around the world, on reading math and science, is going to provoke a lot of hand-wringing in the United States, and for good reason. U.S. students are sliding down the rankings in all three categories and perform lower than the OECD average in math.

The second wave of coverage is going to be about how East Asian countries are now dominating the rankings. There’s some truth to this narrative too, but also some problems with it.

The three “countries” at the top of the PISA rankings are in fact cities—Shanghai, Singapore, and Hong Kong—as is No. 6, Macau. These are all big cities with great schools by any standards, but comparing them against large, geographically dispersed countries is a little misleading.

Shanghai’s No. 1 spot on the rankings is particularly problematic. Singapore is an independent country, obviously, and Hong Kong and Macau are autonomous regions, but why just Shanghai and not the rest of China?

As Tom Loveless for the Brookings Institution wrote earlier this year, “China has an unusual arrangement with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the organization responsible for PISA. Other provinces took the 2009 PISA test, but the Chinese government only allowed the release of Shanghai’s scores.”

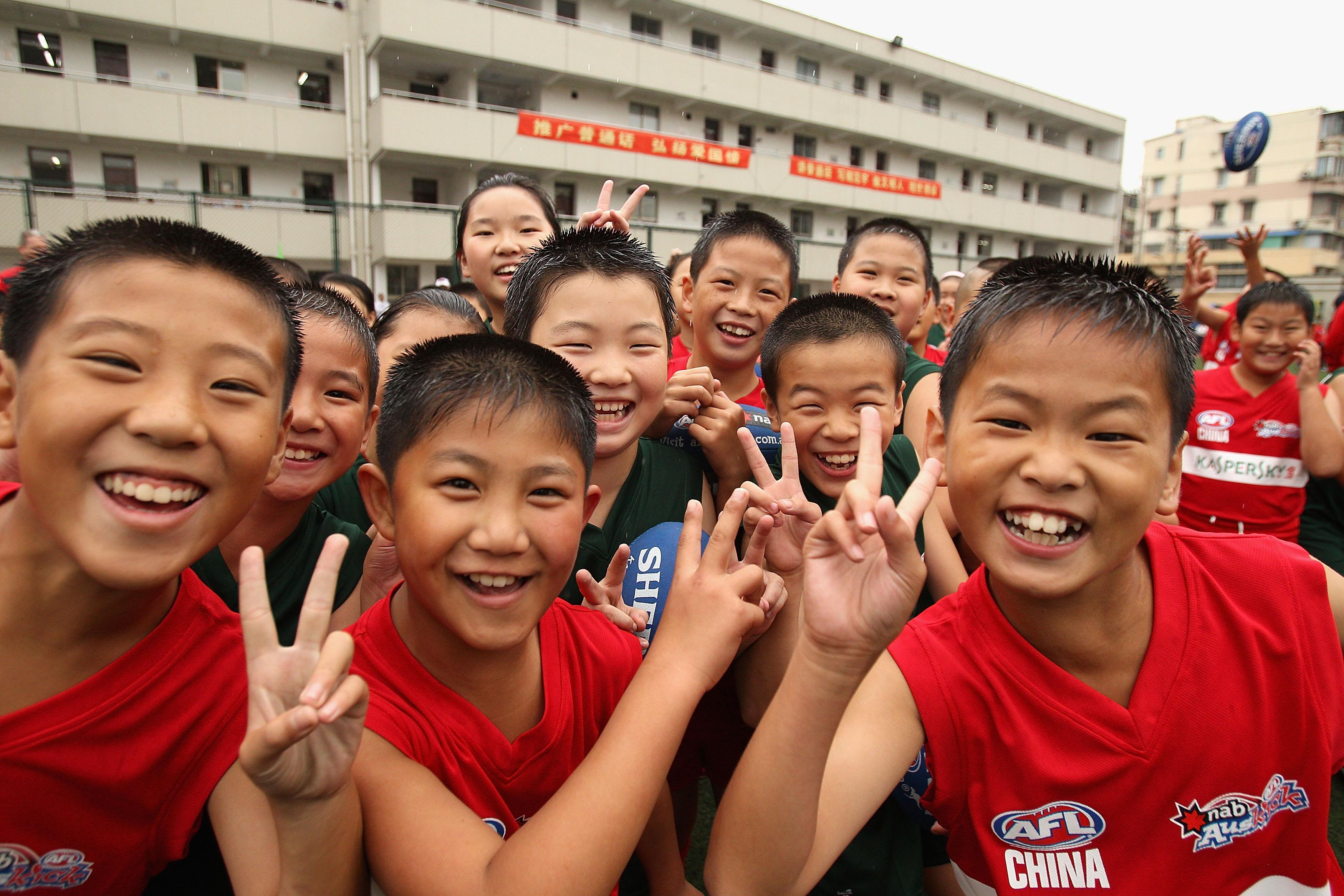

As you might imagine, conditions in a global financial capital are somewhat different from the rest of China, a country where 66 percent of children still live in rural areas:

How dissimilar is Shanghai to the rest of China? Shanghai’s population of 23-24 million people makes it about 1.7 percent of China’s estimated 1.35 billion people. Shanghai is a Province-level municipality and has historically attracted the nation’s elites. About 84 percent of Shanghai high school graduates go to college, compared to 24 percent nationally. Shanghai’s per capita GDP is more than twice that of China as a whole. And Shanghai’s parents invest heavily in their children’s education outside of school. According to deputy principal and director of the International Division at Peking University High School, Jiang Xuegin:

“Shanghai parents will annually spend on average of 6,000 yuan on English and math tutors and 9,600 yuan on weekend activities, such as tennis and piano. During the high school years, annual tutoring costs shoot up to 30,000 yuan and the cost of activities doubles to 19,200 yuan.”

The typical Chinese worker cannot afford such vast sums. Consider this: at the high school level, the total expenses for tutoring and weekend activities in Shanghai exceed what the average Chinese worker makes in a year (about 42,000 yuan or $6,861).

Despite this, we’re likely to see quite a few headlines, as we did in past years, about “Chinese” students outperforming Americans. Several U.S. states also participated for the first time as separate systems. The PISA results note that on reading scores, “Massachusetts was outperformed by only three education systems, and Connecticut by four.” This is impressive for those states, but nobody would ever think of using these results as proxies for the U.S. education system as a whole. The OECD should stop letting China do the same.