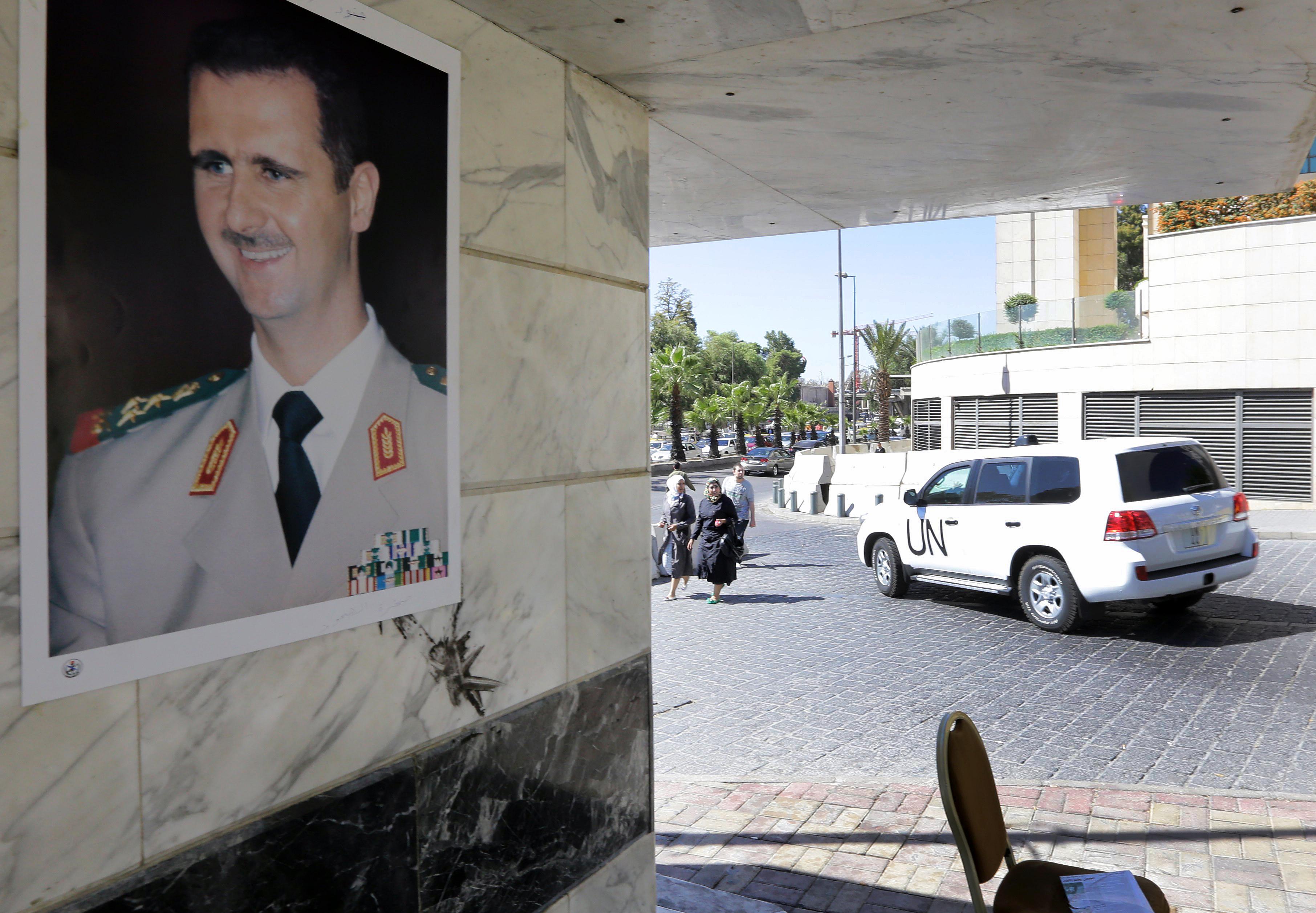

Shortly after the Syrian gas attacks on Aug. 21, I talked with political scientist Alastair Smith on this blog about how the extreme measure of using chemical weapons could actually turn out to be smart domestic politics, since it signaled to Bashar al-Assad’s key supporters, mostly from his Alawite religious group, that they would likely face brutal repercussions if the regime falls, making the prospect of more high-profile defections less likely. It has turned out well for Assad internationally as well. Syria’s entry into the chemical weapons convention and the process of removing the weapons has restored a measure of legitimacy to his regime and taken the focus off the rest of the fighting.

In a recent article for the Journal of Democracy, political scientist Steve Heydemann of Georgetown and the U.S. Institute of Peace takes this line of thinking a bit farther. He argues that while the regime still may fall, and that the utter destruction of much of Syria’s infrastructure and sectarian divisions caused by the war may make it harder for the government to control all of Syria’s territory, the adaptations the regime has made to survive this war are could make the government better able to put down any potential threats in a post-war environment.

“What seems more plausible is that the repressive and corrupt authoritarian regime that entered civil war in 2011 will emerge from it as an even more brutal, narrowly sectarian, and militarized version of its former self,” he writes.

He writes that the regime has promoted “defensive solidarity among the regime’s core social base in the Alawite community and non-Muslim minorities” and “reconfigured the security sector, including the armed forces,paramilitary criminal networks, and the intelligence and security apparatus to confront forms of resistance (in particular, the decentralized guerrilla tactics of armed insurgents) for which the security sector was unprepared and poorly trained.”

He describes the Syrian government we’re likely to see after the war as “a regime whose social base has been welded into the security apparat; ordinary citizens who now act as agents of regime repression; regime-society relations defined to a disturbing degree by shared participation in repression.”

Not all governments, it should be said, responded to the Arab Spring this way. Morocco and Jordan responded to protests by instituting some minor reforms. The Gulf States have poured billions into social spending to keep their populations from rising up.

These countries have avoided the kind of carnage we’ve seen in Syria. But on the other hand, citizens in these countries have learned they can win concessions through the threat of civil unrest and may continue to up the ante.

The lesson the Assad regime took from Tunisia and Egypt was evidently, as Heydemann puts it, that these “regimes had failed because they did not crush the protests instantly.” The consequences of that conclusion have been dire for Syria, but if the regime can survive the war, other governments may, unfortunately, take note.