The plot of the new film Gravity concerns astronauts who find themselves in peril after their shuttle is damaged by space debris. As economists Nodir Adilov, Peter Alexander, and Brendan Cunningham point out in a recent research paper, debris is a very real and growing problem.

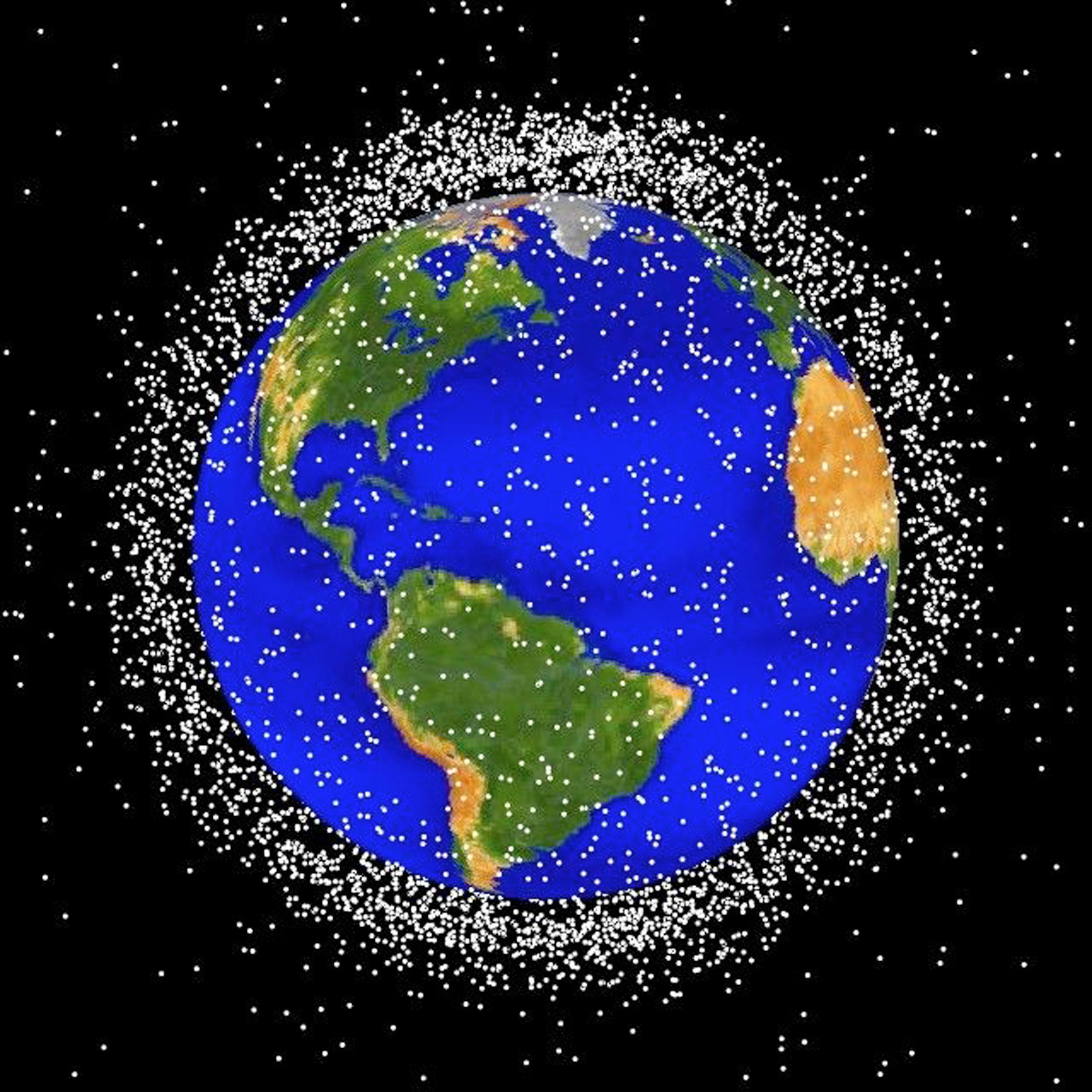

More than 21,000 pieces of junk over 4 inches and half a million larger than 10 cm currently orbit the planet. Debris left over from a 2007 Chinese missile test took out a Russian satellite earlier this year. Last year, the crew of the International Space Station had to shelter in escape capsules during the station’s third near collision with space debris in 12 years.

What makes the problem worse, as Adilov, Alexander, and Cunningham explain, is that “unlike standard terrestrial pollution, debris propagates additional pollution. Thus, for example, a collision between a satellite and a piece of debris, or even between two pieces of debris, creates additional debris which further increases the likelihood of other debris creating collisions.”

As far back as the 1970s, scientists have worried that space junk collisions could create a cascade of debris generation that could eventually render orbital space unusable.

The solution to the problem is fewer satellite launches combined with spending on technologies to minimize debris or remove it. (Such technologies have barely been developed.) The authors argue that voluntary guidelines to reduce debris will prove insufficient as more private companies and governments enter orbit.

”Competitive firms will generally choose the least-costly mitigation technology, which in turn generates the most debris, because it carries the lowest cost for the firm,” they write.

Their solution is a tax on satellite launches that “induces competitive firms to choose the socially optimal level of launches,” though they acknowledge that “the practical problem of getting various economic actors to agree to a launch tax is daunting, to say the least.”

The European Union has put forward a non-binding Space Code of Conduct and there’s been some movement toward its adoption, a growing priority with more countries and firms launching objects into orbit. But I’m not hugely optimistic about any kind of binding treaty that includes an internationally-mandated space tax making it through the U.S. Congress any time soon.

(Via Marginal Revolution)