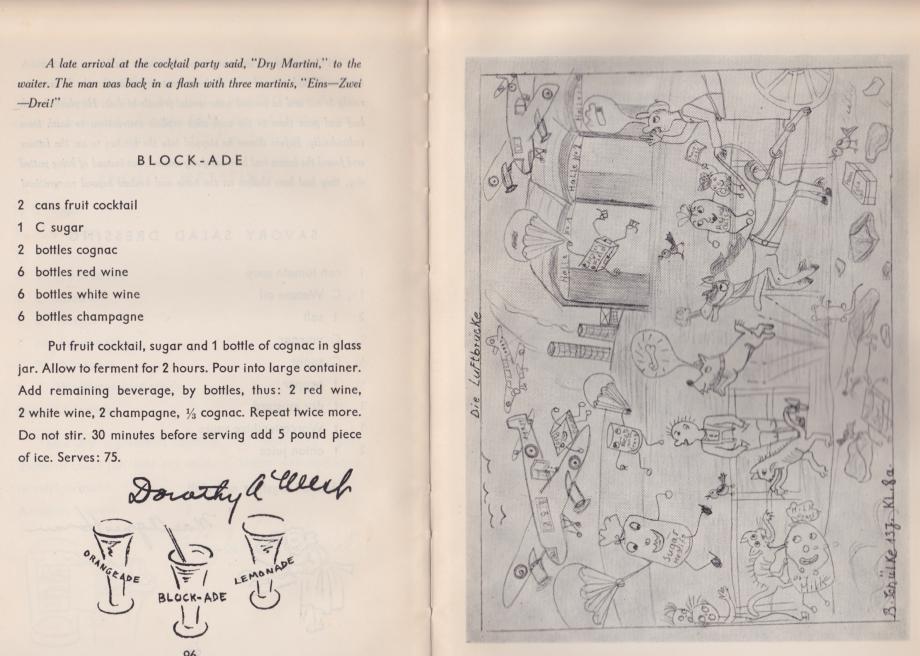

In the summer of 1948, nearly 1,000 American women, wives of military and civilian occupation personnel, found themselves in the middle of what would become the first major crisis of the new Cold War: the Berlin Blockade. By the end of June, the Soviets had cut off road and rail access to the city, severely rationed its electricity and water, and hoped to drive Western forces from the war-damaged German capital. The Allies responded with an ambitious plan: an airlift. Approximately every 30 seconds, around the clock, for 15 months, a plane would land or take off, supplying the beleaguered city with more than 2 million tons of goods.

The American women—and their 744 children—would have been forgiven for abandoning their new home front. Yet, they stayed. They were committed, the Chicago Tribune reported at the time, to “encouraging Berliners frightened by the prospect of Russia taking full control of the city.” The American Women’s Club of Berlin even created this cookbook, Operation Vittles, published in January 1949, to commemorate their resolve and finance their charitable activities. (You can read a scan of the whole cookbook at this link.)

“The American Women in Blockaded Berlin,” Operation Vittles (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag, 1949).

Operation Vittles is stuffed with a postwar spirit of international aid, cheerful sacrifice, and collective responsibility. Some of the recipes are simple, like cheese on toast, while others include lemons and sherry, tastes of Western prosperity and hope in the middle of geopolitical crisis. The book celebrates the “happy group of wives who attempted to obtain American meals,” and anecdotes make light of shortages and shutdowns: Children charmingly nickname the planes “noodle bombers,” while electricity cut-offs mean that one lamb roast played a 22-hour game of “musical ovens” around the city. The Americans didn’t just teach German women about the joys of refrigeration; rightly or not, they also modeled the potential and benevolence of their country’s power and values.

Yet, these anecdotes also reveal an American character perhaps overseasoned with self-assuredness. Though affectionate, the authors all too often cast “the many excellent [German] cooks” they encountered as culinary conservatives, simpletons who complained about “the puzzling variety in the American diet” and its tendency for newness. In one instance, they roast a German cook who foolishly “stuffed [a chicken] with one cup poultry seasoning and one tablespoon breadcrumbs!” Elsewhere, they playfully mock the Germans’ taste for heavy bread and cold food, not caring to mention if these preferences stemmed from cultural difference or lingering habits of wartime conservation.

“The American Women in Blockaded Berlin,” Operation Vittles (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag, 1949).

Operation Vittles is a testament to a group of Americans who tried to make do and do good. The quotidian work of cooking and eating was political action during the Cold War, holding more than just a culinary front against a Soviet menace. In taking large responsibility for a free West Berlin and a free world, American soldiers and their families shouldered much of the burden of constructing a liberal global framework. But this postwar order, so essential for European prosperity, would also carry the seeds of American hubris and exceptionalism that we still reckon with today.