After a six-year medical apprenticeship that began at the age of 14, Alexander Anderson became the resident physician at New York’s Bellevue Hospital. It was the peak of the city’s 1795 yellow fever epidemic, but Anderson was “determined to do the Lord’s work,” writes David Oshinsky in his new book, Bellevue: Three Centuries of Medicine and Mayhem at America’s Most Storied Hospital.

For three months, Dr. Anderson watched helplessly as patient after patient succumbed to a disease (flavivirus) for which the cause was unknown, and the best “treatment” was bloodletting or a dose of mercury chloride. When the first frosts arrived and the plague (which, we now know, is transmitted via mosquito bites) passed, Anderson, whose father was a printer, confided to his diary, “I cannot help looking back to my engraving table and thinking it is a fitter station for me.”

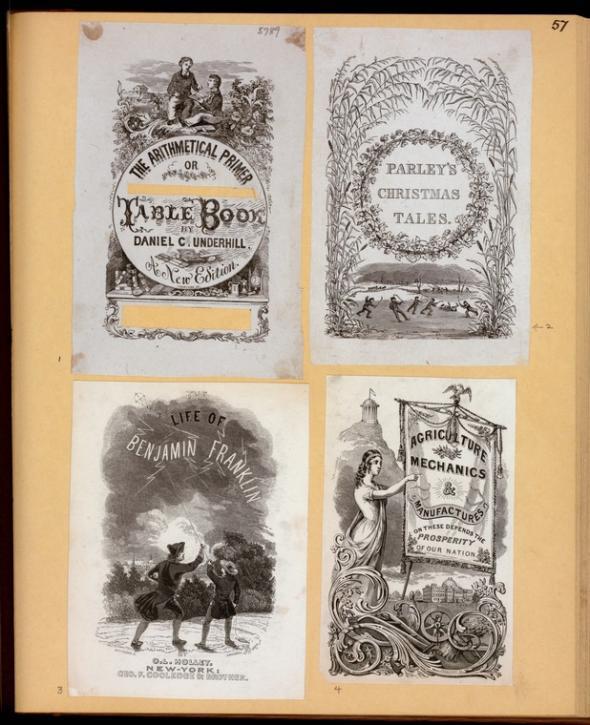

Trading his lancet for a chisel, Anderson produced the first American wood-engraved volume, Looking-Glass for the Mind, and opened a children’s bookshop, aptly named the Lilliputian Book-Store. Pressed for income, however, he resumed his role at Bellevue during the deadlier 1798 outbreak of yellow fever. He survived, but thousands did not, including his infant son, wife, father, mother, and brother. That string of tragedies compelled Anderson to abandon “the medical career his parents had forced upon him,” writes Oshinsky.

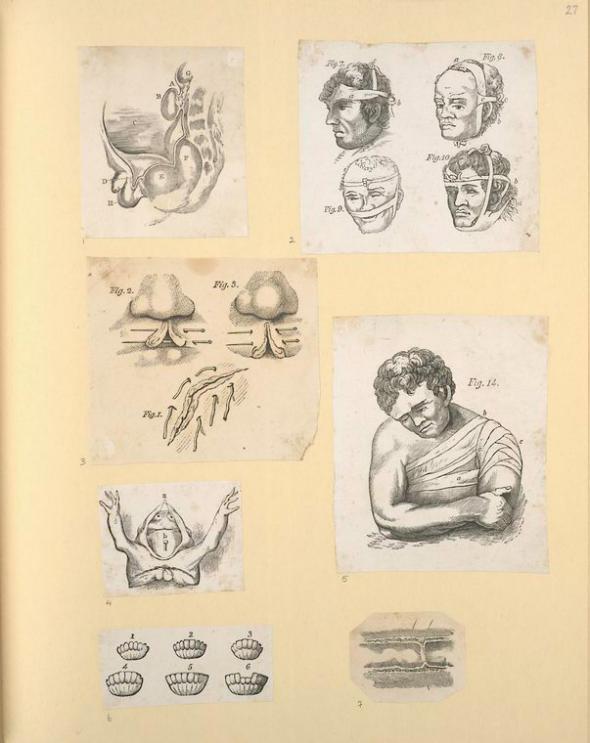

Anderson returned to wood engraving, ultimately earning the titles “America’s First Illustrator” and “The Father of American Wood Engraving,” the latter inscribed on his tombstone in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. Twelve scrapbooks digitized by the New York Public Library showcase his inexhaustible output: farm animals, children, Shakespearean scenes, product labels, newspaper flags, heraldic shields, bookplates, even anatomical illustrations (a form for which he was ideally suited).

New York Public Library

“Anderson was the first person in this country to engrave on end-grain boxwood, thus introducing a medium that would economically allow prolific illustration in 19th-century printing,” writes Jane R. Pomeroy, who published a three-volume bibliography of his work, Alexander Anderson, 1775–1870, Wood Engraver and Illustrator, in 2005.

Forgotten as a physician, Anderson was destined to make his mark as an artist. He died in 1870, at the age of 95, having illustrated more than 2,000 books.